Road, Royal Court review - poetry amidst the pain | reviews, news & interviews

Road, Royal Court review - poetry amidst the pain

Road, Royal Court review - poetry amidst the pain

John Tiffany leads Jim Cartwright's debut play towards the sublime

Who'd have guessed that the London theatre scene at present would be so devoted to the numinous? Hard on the heels of Girl from the North Country, which locates moments of transcendence in hard-scrabble Depression-era lives, along comes John Tiffany's deeply tender revival of Jim Cartwright's vaunted 1986 play Road, which tempers its landscape of pain with an abundance of poetry.

As it happens, one has to wait till after the interval to feel the gathering force of Harry Potter and the Cursed Child director Tiffany's approach here. But come the climactic scene in which a mismatched Lancashire quartet of would-be lovers find release in Otis Redding, and you've got as viscerally affecting an experience as anyone could wish. That sequence, in turn, is capped by an extended (and wordless) dance-theatre illustration of the communal as its own best antidote to life's abrasions: a state of grace that gives the lie to those who think of Road merely as a report from the Thatcher-era frontline of the gritty and the grim.  I was around for this play's premiere in the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs all those years ago, which led to a further life on the Court mainstage; at that point the since-deceased Ian Dury joined the cast as Scullery, our rough-and-ready tour guide to the unfolding patchwork quilt of dispossession and deprivation. But performed promenade-style so that the actors and the audience folded in upon one another. the play didn't seem as shot through with romanticism as it does this time around. From the soaring tones of Judy Garland (a crucial figure, of course, in Cartwright's later play and film about the freakishly gifted Little Voice) onwards, this is a portrait of existence lived on the margins that nonetheless knows its musical theatre.

I was around for this play's premiere in the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs all those years ago, which led to a further life on the Court mainstage; at that point the since-deceased Ian Dury joined the cast as Scullery, our rough-and-ready tour guide to the unfolding patchwork quilt of dispossession and deprivation. But performed promenade-style so that the actors and the audience folded in upon one another. the play didn't seem as shot through with romanticism as it does this time around. From the soaring tones of Judy Garland (a crucial figure, of course, in Cartwright's later play and film about the freakishly gifted Little Voice) onwards, this is a portrait of existence lived on the margins that nonetheless knows its musical theatre.

That's to say, Cartwright offers up drunkenness aplenty, not to mention fumbled sexual encounters guaranteed to make one squirm: Game of Thrones alumna Michelle Fairley (pictured above with Mike Noble) fields the most extreme of those with gusto. (Her hair is a scenic effect in itself.)

But for all the bluntly articulated despair ("why is the world so tough?" is a representative rhetorical question), these people nonetheless exist a song lyric away from salvation. Lemn Sissay's large-eyed, cajoling Scullery functions as Road's very own Emcee, presiding over an unnamed street that talks one moment of "England in pieces" and quotes "I Got Rhythm" the next. Passing references elsewhere to "a can-can", and a cribbed lyric from Annie Get Your Gun, make one wonder what might happen were this clearly expressive assemblage to form their own am-dram society. Swan Lake gets a workout, as well, Tchaikovsky accompanied this time out by Scullery twirling a shopping trolley with unbridled abandon.

But for all the bluntly articulated despair ("why is the world so tough?" is a representative rhetorical question), these people nonetheless exist a song lyric away from salvation. Lemn Sissay's large-eyed, cajoling Scullery functions as Road's very own Emcee, presiding over an unnamed street that talks one moment of "England in pieces" and quotes "I Got Rhythm" the next. Passing references elsewhere to "a can-can", and a cribbed lyric from Annie Get Your Gun, make one wonder what might happen were this clearly expressive assemblage to form their own am-dram society. Swan Lake gets a workout, as well, Tchaikovsky accompanied this time out by Scullery twirling a shopping trolley with unbridled abandon.

The first half has a surprisingly presentational feel, amplified by a striking design from Chloe Lamford that encloses numerous scenes within a begrimed cube that rises up through the stage floor. In contrast with steps that lead from the stage into the audience so that Scullery can scuttle amongst playgoers at will, the scenic conceit (deliberately, one assumes) emphasises solitude and isolation, so that the final coming together via movement – these disparate souls a community at last – achieves a redoubled force. Elbow's "Lippy Kids", a song clearly unavailable to Cartwright way back when, ramps up the pathos, its talk of golden days a modern-day complement to that place "over the rainbow" that cascades through the auditorium at the start.

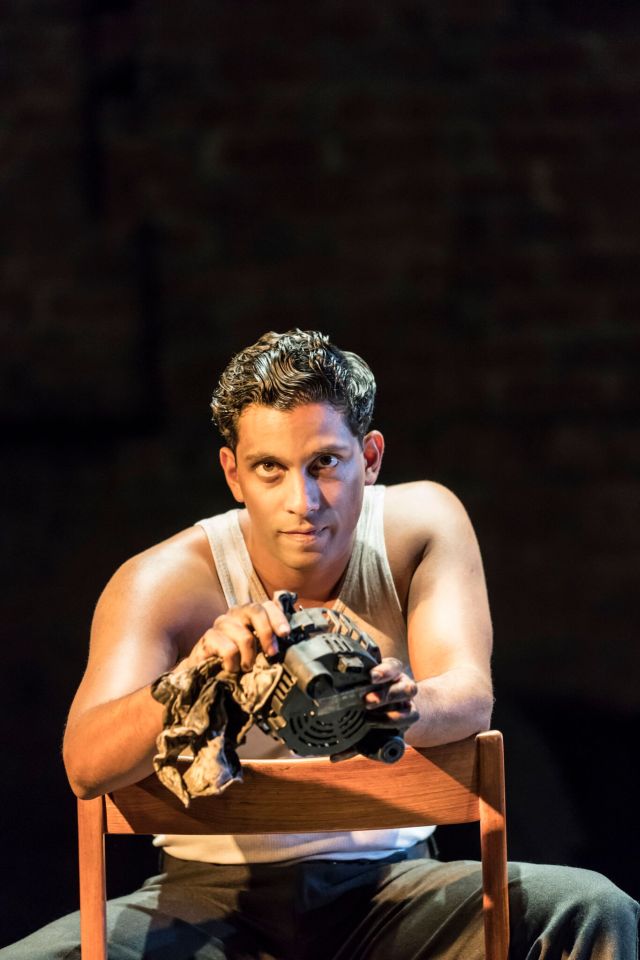

The parade of personages allows for multiple set pieces which Tiffany's cast bat out of the park, whether one is admiring Mark Hadfield's Alan Bennett-esque portrait of alone-ness or the ever-welcome Shane Zaza (pictured above) pondering "death with a big D" as he shfts this way and that in bed. (Cartwright wrote his own play called Bed in 1994.) The redoubtable June Watson juggles multiple roles, at no point more startlingly than when she trills "alley oop" while powdering her face.

Indeed, in contrast to so many Court signature texts, Road in this reckoning suggests a way forward from the depths of despondency, however little things may have changed in our austerity-plagued land today. Just watch as those bodies at the end form and re-form, this lippy, drink-sodden set of individuals newly reassembled as one. From mining corridors of blight and hopelessness that owe more than a passing nod to Beckett, the production's lasting proviso would appear to be the need to connect. These characters aren't the only ones, I imagine, who would drink to that.

more Theatre

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Underdog: the Other, Other Brontë, National Theatre review - enjoyably comic if caricatured sibling rivalry

Gemma Whelan discovers a mean streak under Charlotte's respectable bonnet

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Long Day's Journey Into Night, Wyndham's Theatre review - O'Neill masterwork is once again driven by its Mary

Patricia Clarkson powers the latest iteration of this great, grievous American drama

Add comment