It’s raining. Not spitting or drizzling, properly raining, with clouds so thick that you know they’re here to stay. Yet rather than take shelter in restaurants and bars, or simply stay at home on this soggy summer night, 7,000 people in a stylish array of plastic macs and souwesters have made their way to the harbourside of the small Austrian town of Bregenz. Why? An annual festival that takes opera to extremes.

We’ve had opera in bunkers and canal barges, beaches and helicopters, pubs and warehouses, so what’s so special about opera on a lake? For one thing, Bregenz isn’t about opera close to the water, tacked onto the edge of a harbour. This is a floating stage, surrounded on all sides by the waters of Lake Constance, a stage so elaborate and specific that it is rebuilt from scratch for each new production – less a floating theatre than a floating world.

The snarling heads of three cartoonish dragons rear out of the lake

The ambition of Bregenz is even more astonishing when you realise that when the festival first launched in 1946 the town didn’t even have its own theatre. The progress from this inaugural performance, staged on two barges moored on the lake, to the extravagant structures now created every year has been swift and a steep. The festival now sprawls across theatre, concert hall and various smaller venues, incorporating drama as well as music into a four-week programme that balances its large-scale, popular lake operas with contemporary and lesser-known works, as well as orchestral concerts.

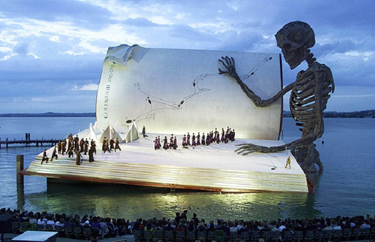

So complex and expensive are the outdoor stagings that each production runs for two years, giving their directors and designers a proper showcase for their extraordinary creations. Johannes Leiacker’s 2007 production of Tosca, built around a giant, Dali-esque eye, proved so striking that producers for Bond film The Quantum of Solace decided to film a large sequence on and around the set. And who could forget Richard Jones and Antony Mcdonald’s visuals (pictured right) for the 1999 Un ballo in maschera – a skeleton waist-deep in the lake delicately turning the page of a book on which the characters moved like running ink blots – that dominated newspapers and news broadcasts around the world when it was revealed.

So complex and expensive are the outdoor stagings that each production runs for two years, giving their directors and designers a proper showcase for their extraordinary creations. Johannes Leiacker’s 2007 production of Tosca, built around a giant, Dali-esque eye, proved so striking that producers for Bond film The Quantum of Solace decided to film a large sequence on and around the set. And who could forget Richard Jones and Antony Mcdonald’s visuals (pictured right) for the 1999 Un ballo in maschera – a skeleton waist-deep in the lake delicately turning the page of a book on which the characters moved like running ink blots – that dominated newspapers and news broadcasts around the world when it was revealed.

2014 hosts the second staging of festival artistic director David Pountney’s The Magic Flute. Walking along the harbour promenade towards the floating Seebühne, the first hint you get of its presence are the snarling heads of three cartoonish dragons who rear out of the lake, gripping a walkway between their teeth. Turn a corner and their patterned bodies are revealed, together with the terraced neon green sphere that makes up the body of designer Johan Engels’ stage.

The whole space is a fantasy, and what better opera to lend itself to wild visual imaginings and sensory experiments than Mozart’s singspiel, with its monsters and magical creatures, sorceresses and enchanted bells. Yes, there’s a darker layer to a piece that has never fully given up its secrets on stage, but leave all that aside and you still have a vivid piece of musical storytelling that can operate far more freely when unshackled from elaborate systems of Masonic or social symbolism.

The whole space is a fantasy, and what better opera to lend itself to wild visual imaginings and sensory experiments than Mozart’s singspiel, with its monsters and magical creatures, sorceresses and enchanted bells. Yes, there’s a darker layer to a piece that has never fully given up its secrets on stage, but leave all that aside and you still have a vivid piece of musical storytelling that can operate far more freely when unshackled from elaborate systems of Masonic or social symbolism.

Relieved of his duty to do anything but entertain, Poutney has a ball. A sequence of ever-more-exotic crafts drift in on the water carrying characters, from the Michelangelo-inspired gilded hand that holds Tamino, to the oversized egg that “hatches” Papagena (pictured below) and the giant turtle who paddles on bearing the three boys. The Queen of the Night’s monster becomes a threatening sea-creature, setting the lake waters boiling with froth before emerging in clasping tentacles. Sarastro’s accolytes are body-suited acrobats, dangling from zip wires and crawling over the set like so many Spiderman tribute acts, stealing away Pamina in a thrilling sequence during the overture in which firework explosions add their own percussion interjections.

The singers – one cast of three who rotate through the show’s long run – were generally solid, with especially strong performances from Nikolai Schukoff’s swaggering Tamino and Gisela Stille’s resourceful Pamina. Only Daniela Fally’s Queen of the Night disappointed, lacking both the power and the control to deliver vocal fireworks needed to match the actual ones on display here.

But a Bregenz production neither sinks nor swims on the quality of the music. This is opera-as-spectacle, opera-as-circus, a summer holiday from the earnest and self-important Regietheater we get year-round in the metropolitan houses, and thoroughly and riotously welcome.

Counterweight to so much froth and excess at this year’s festival was a moving concert of Britten’s War Requiem. Scheduled on 28 July, the performance marked the exact anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War and broadly recreated the composer’s original intention to have a Russian soprano soloist (here, perhaps even more poignantly, the Ukrainian Oksana Dyka), a German baritone (Michael Volle) and an English tenor (Allan Clayton, pictured below). They were joined by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra under the baton of their newly-appointed music director Philippe Jordan and a chorus that combined Bregenz’s own festival chorus with the Prague Philharmonic Choir.

Jordan officially takes up his new role with the VSO in October, and his appointment marks an exciting watershed in the musical life of an orchestra who have always had an active and unusual committment to new music. Jordan's relationship with the ensemble extends back a decade, and it shows. There's no indulgence and still less affectation in the young conductor's style, and here the orchestra gave him the forthright and direct delivery he asked for, even if the gilded brass playing at times tended to the intrusively beautiful in this sombre work.

Bregenz’s concert hall has an unusually deep stage, serving as it must for both opera and orchestral performances, which set the choir a long way back. The effect was oddly muted at times, like a sonic sepia photograph – evocative, but indistinct. While the soft-focus worked well for the comforting haze of the Recordare and the alien mutterings of the opening Requiem aeternam, it denied the work’s moments of confrontation and protest the bladed edge that the music demands.

Bregenz’s concert hall has an unusually deep stage, serving as it must for both opera and orchestral performances, which set the choir a long way back. The effect was oddly muted at times, like a sonic sepia photograph – evocative, but indistinct. While the soft-focus worked well for the comforting haze of the Recordare and the alien mutterings of the opening Requiem aeternam, it denied the work’s moments of confrontation and protest the bladed edge that the music demands.

Much of the evening’s pathos was down to Allan Clayton who brought lieder-like intimacy to his sections, drawing us close before horrifying us with the tale of Abraham and Isaac, and balancing bitterness and urgent lyricism in the “One ever hangs” section of the Agnus Dei. Michael Volle’s undemonstrative delivery was anchored by his careful vocal shading, refusing to overplay the shock of his climactic “I am the enemy you killed, my friend”. Only Dyka (pictured left) seemed to misunderstand the occasion, never raising her eyes from her copy, though gesturing extensively throughout. Singing the Sanctus as though she were singing “Vissi d’arte”, her voice may have coaxed beautiful shapes from Britten’s phrases, but seemed unable or unwilling to look beyond their surface.

Much of the evening’s pathos was down to Allan Clayton who brought lieder-like intimacy to his sections, drawing us close before horrifying us with the tale of Abraham and Isaac, and balancing bitterness and urgent lyricism in the “One ever hangs” section of the Agnus Dei. Michael Volle’s undemonstrative delivery was anchored by his careful vocal shading, refusing to overplay the shock of his climactic “I am the enemy you killed, my friend”. Only Dyka (pictured left) seemed to misunderstand the occasion, never raising her eyes from her copy, though gesturing extensively throughout. Singing the Sanctus as though she were singing “Vissi d’arte”, her voice may have coaxed beautiful shapes from Britten’s phrases, but seemed unable or unwilling to look beyond their surface.

Perhaps most moving here though was not the music itself but the silence that followed – held infinitely long by Jordan – saying what even Britten’s music could not about not only Ypres and the Somme, but also Syria, Gaza, Afghanistan and Iraq.

Next year’s Bregenz Festival marks the start of a new era, when Elisabeth Sobotka of Graz Opera takes over from Pountney as artistic director. Pountney’s reign has closed on a joyous high, and Sobotka looks set to sustain this, promising “evolution rather than revolution” in her future plans. With Turandot scheduled for 2015 and Carmen (directed by the Royal Opera House’s own Kasper Holten) for 2017, it’s clear that she’s not afraid to embrace Bregenz’s populist credentials. Can she top floating turtles and firework spectaculars? We can only wait and watch as Poutney’s magical world is dismantled and a brand new structure takes its place on the lake.

- The Magic Flute is at the Bregenz Festival until 25 August, 2014

- This September Philippe Jordan's first recording with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra - Tchaikovsky's Symphony No 6 - will be released on the orchestra's own label.

Add comment