The British film industry of the 1950s underwent intense financial pressure. Audiences were changing and diminishing, and earlier attempts to protect domestic production had often backfired, exposing just how fragile local filmmaking had become and how increasingly dependent it was on American money.

To slow the drain of dollars overseas, US studios were encouraged to reinvest their UK profits locally. Columbia arrived later than most but, once established, the studio built a web of partnerships that fused Hollywood star power and production methods with British locations, writers, directors, actors, and crews.

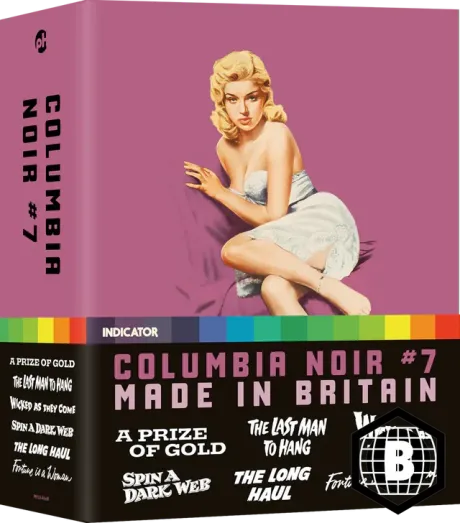

The films gathered in Indicator’s Columbia Noir #7: Made in Britain Blu-ray set are crime stories shaped by war damage, trauma, displacement, and the socioeconomic anxieties of a country still finding its feet, but they are not of Britain exclusively.

Featuring courtroom battles, underworld rackets, impossible heists, doomed lorry drivers, and ruthless social climbers, these six titles trace a varied mix of noir aesthetics and themes that migrated and endured in post-war Europe.

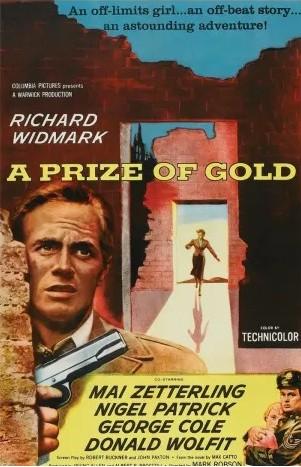

A standout is the Technicolor A Prize of Gold (1955), based on Max Catto’s 1953 novel and partially shot in West Berlin. The shattered city dominates the first half, in which the mood leans closer to wartime melodrama than noir. American director Mark Robson and producers Cubby Broccoli (who launched James Bond seven years later) and Irving Allen applied their Warwick Films formula of dropping American stars into perilous foreign terrain.

Richard Widmark, newly freed from his 20th Century-Fox contract, plays a US Air Force sergeant whose infatuation for a teacher (Mai Zetterling) of war orphans propels him into planning a morally compromising gold bullion heist. Filmed in a measured, less frantic register than Night and the City, Jules Dassin’s 1950 British noir with Widmark, the movie channels the star’s signature survivalism through a ruin-strewn landscape, rendering it a distinctive Columbia British noir curio.

Terence Fisher’s tightly budgeted courtroom thriller The Last Man to Hang (1956) fuses the classic English whodunit with a strong noir sensibility. Adapted from Gerald Bullett’s 1935 novel The Jury, it examines class, conscience, and the question of capital punishment at the time of the 1956 parliamentary debate on it.

Tom Conway presents a stiff, exhausted figure as Sir Roderick Strood, a celebrated music critic accused of murdering his emotionally dependent and obsessively jealous wife (played by the quietly compelling Elizabeth Sellars). Although the final twist strains credibility, Fisher’s direction is assured. Vignettes of the jury members at the Old Bailey offer discerning glimpses of English society. The Last Man to Hang is a flawed but absorbing B feature.

Equally engaging is Wicked as They Come (1956), one of two Arlene Dahl vehicles in the set. Director Ken Hughes stylishly conveys a world of social climbing and sexual leverage. Following in the footsteps of Barbara Stanwyck in the pre-Code Baby Face, Dahl is magnetic if a trifle too sophisticated as a factory girl who wins a beauty contest and ascends from the New York slums to high society in London and Paris. Michael Goodliffe, Herbert Marshall, and Philip Carey play the suitors.

Hughes leans into the story’s erotic charge, pushing its temperature higher than the toned-down adaptation of Bill S Ballinger’s 1950 hard-boiled novel Portrait in Smoke. His expressive use of space turns mirrors into instruments of duplicity, framing ambition as a performance staged through skewed reflections in a genuine noir texture.

Robert Westerby’s 1937 novel Wide Boys Never Work was the source of Vernon Sewell’s Soho Incident (1956), a superbly atmospheric depiction of London’s post-war criminal underworld. Lee Patterson plays a disenchanted Canadian soldier turned boxer who is drawn by Faith Domergue’s sultry femme fatale to work for her Sicilian mobster brother (Martin Benson).

Shot extensively on location, the film moves through Soho’s streets, markets, and clubs with long, fluid tracking shots that capture its seedy glamour with striking immediacy. Basil Emmott’s cinematography and Ken Adam’s inventive art direction give the film a visual élan that belies its modest budget.

Starring two outsized stars, Hollywood import Victor Mature and local sensation Diana Dors, The Long Haul (1957) was adapted by director Ken Hughes from Mervyn Mills’s eponymous novel. Unlike most noirs in this set, which focus on criminal activity and monetary gain, the film examines the personal consequences of displacement and fractured domestic life.

Mature plays a discharged GI stranded in Liverpool (Hughes’s birthplace) and eager to return to the US but bound by his British wife (Gene Anderson) and child. He becomes entangled with the corrupt boss (Patrick Allen) of a haulage firm and begins a dangerous affair with the latter’s girlfriend (Dors). The film culminates in a spectacular smuggling run in the Scottish Highlands, but its main strength lies its portrayal of rootlessness, dislocation, and longing. (Pictured below: Gene Anderson and Victor Mature in The Long Haul)

Unmistakably recalling the start of Hitchcock’s Rebecca, the dynamic prologue of Fortune Is a Woman (1957) moves from a metronome’s rhythmic beat to the sweep of windscreen wipers on a rain-lashed night, before guiding us toward Lowis Manor, the provisional Manderley of director Sidney Gilliat’s Gothic-inflected mystery, co-adapted from Winston Graham’s 1952 thriller.

Insurance assessor Oliver Branwell (Jack Hawkins) is sent to the manor after a suspicious fire. He meets its owner (Dennis Price), his mother (Violet Farebrother), his American wife Sarah (Arlene Dahl), an old flame of Branwell. (The US release title She Played With Fire was more fitting than the British one.) Playing another of these dubious types, Christopher Lee makes a brief but memorable appearance.

As Branwell is drawn into a case of arson and art forgery, Gerald Gibbs’s cinematography turns the house into a brooding presence, a relic of pre-war grandeur marked by everything that followed. “One must learn to forgive the times one lives in,” Farebrother’s character quietly observes, an apt comment on the moral quagmire common to the films in this 1950s British noir collection.

The supplements include a booklet of essays, promotional materials, and interviews with members of the casts and crews. Each Blu-ray features in-depth audio commentaries. Additional films function as mini time capsules: This Little Ship (1953), narrated by Jack Hawkins, commemorates Britain’s first nuclear test and the doomed HMS Plym; Soho (1943), an amateur documentary made by Hughes, captures wartime life in the district; and The Long Night Haul (1956) explores the UK’s haulage network. Taken together, these resonant works offer a vivid, immersive portrait of the world that spawned the six noirs.

Add comment