Natasha Brown: Assembly review - turning personal crisis into perfect criticism | reviews, news & interviews

Natasha Brown: Assembly review - turning personal crisis into perfect criticism

Natasha Brown: Assembly review - turning personal crisis into perfect criticism

A journey to the heart of the establishment to inspect its shaking foundations

School assembly: one of the many great traditions to be upended by the pandemic. According to this novel, that might not be such a bad thing.

It’s a story. There are challenges. There’s hard work, pulling up laces, rolling up shirtsleeves, and forcing yourself. Up. Overcoming, transcending, et cetera. You’ve heard it before. It’s not my life, but it’s illuminated two metres tall behind me and I’m speaking it into the soft, malleable faces tilted forwards on uniformed shoulders.

Illuminated, yes, but hardly illuminating. It tells us nothing about this story, this storyteller. Then again, neither does Assembly. We don’t even learn her name. We learn much more, even in passing, about those who surround her: friends, neighbours, acquaintances. Strangers, too, who freely dispense racial slurs at her on the Tube, in the street -– although, strictly speaking, in these cases we don’t so much learn as get to confirm what we already know.

Besides the everyday people who seem to resent her presence, there are the suited and booted men who resent her success. When a push for diversity at work sees her seemingly float above her colleagues to a top managerial role, they simply can’t resist telling her how it is. She’s at an advantage because she’s Black. “It’s so much easier for you blacks and Hispanics”. She’s at an advantage because she’s a woman, who can simply sleep her way to the top. It never occurs to them, of course, that this might just be their hallowed meritocracy at work. Besides them, there’s her ex-boss Lou – who she was, in fact, sleeping with, but aimlessly – who thinks he “gets it” because he’s an immigrant who grew up poor (which is not quite “it”). There’s also her rich home counties-grown boyfriend who thinks he’s already got it because he’s got her (which is far from “it”). They may be no “it” to get.

The boyfriend also remains nameless, the yin to our narrator’s yang. In fact, the other way round. The narrator comes to realise she is the “contrast”, the “sharp, black outline” he, and by extension his race (conceived of as a race), cannot live without. He’s nameless because, like her, he cannot truly be said to exist outside that narrative, these pages; outside black and white. He’s increasingly called “the son”, another half-owned identity, as we drift ever closer to the dreaded garden party at his family’s countryside manor the "plot" is supposedly heading towards and as our narrator migrates ever closer to the heart of the establishment that once made (still makes) a profit off people like her; bodies like hers.

The parents’ forced attempts to make her feel "at home" are, in this respect, doubly awkward. The only person not to see her as an asset, an analogy or a nuisance is her friend Rach who gives her the space just to be herself, to be “un-storied and direct”. But even this relationship is shot through with certain fictions. The two spend their time together mercilessly upgrading, optimising. “We made lists, reviewed our five-year plans and crunched out the Teflon-lined stomachs necessary for execution.” This is not an extension of a work life but life as work. No wonder she wants to quit.

A cancer diagnosis, snippets of which pop up throughout the book, seems a gift; a golden opportunity to just stop. Some readers might take issue with Brown’s use of this subject but, particularly filtered through her freshly clarified yet darkly comic style, the disease’s incorporation and light treatment (or non-treatment) conveys exactly the desire to no longer meet the requirements of a certain type of story. Cancer, the book seems to say, is just the thing a novel would form around, like a scab; would anaesthetise. Here it’s just one among many threads Brown handles and allowing it to weave in and out of the texture, in and amongst potted histories of private and public brutalities, allows her to question our ideas about survival and exactly what it means, especially for people of colour. If I am (or we are) not thriving, and only surviving, even on the ladder’s top rungs, why continue striving? Why not live and let die what would systematically and systemically be killed more slowly by other means? There are, of course, no easy answers.

As its central character (and the very notion of character) breaks down, so does Assembly – into pithy paragraphs and insights picking apart some of the illusions we, particularly in the UK, live under; are kept under. Some more than others. It knows stories are powerful things, that is, full of power, both its past and its potential – to humiliate, assimilate, eradicate. Brown covers a lot of this ground in a breathtakingly short space of time (100 pages) and in order to do so it’s no surprise the book degenerates or, rather, devolves to cultural criticism as criticism is one way to tell stories – tell, as in to account for them, to hold them to account – without necessarily having to tell them. It’s a way, at least in theory, of being direct, un-storied: yourself. Unless, of course, you are compelled to assemble that self into an article, a review, a thesis, a novel, a "work" - all of which Assembly at one point or another resembles. As an unexpected, and unexpectedly poetic, footnote late in the book observes, “It is remarkable, even/in the ostensible privacy of my own thoughts/I feel/(still)/compelled/to restrict what I say.” Let’s hope Natasha Brown keeps pushing at the limits: having these thoughts; sharing them.

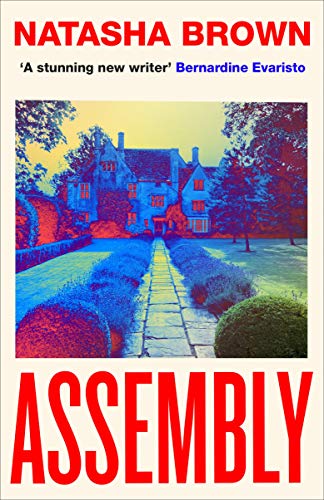

- Assembly by Natasha Brown (Penguin, £12.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Jessica Duchen: Myra Hess - National Treasure review - well-told life of a pioneering musician

Biography of the groundbreaking British pianist who was a hero of the Blitz

Shon Faye: Love in Exile review - the greatest feeling

Love comes under the microscope in this heartfelt analysis of the personal and political

Shon Faye: Love in Exile review - the greatest feeling

Love comes under the microscope in this heartfelt analysis of the personal and political

Philip Marsden: Under a Metal Sky review - rock and awe

Myths, mines, and mankind combine in this wide-eyed reading of the earth beneath our feet

Philip Marsden: Under a Metal Sky review - rock and awe

Myths, mines, and mankind combine in this wide-eyed reading of the earth beneath our feet

Add comment