Blu-ray: Funeral Parade of Roses | reviews, news & interviews

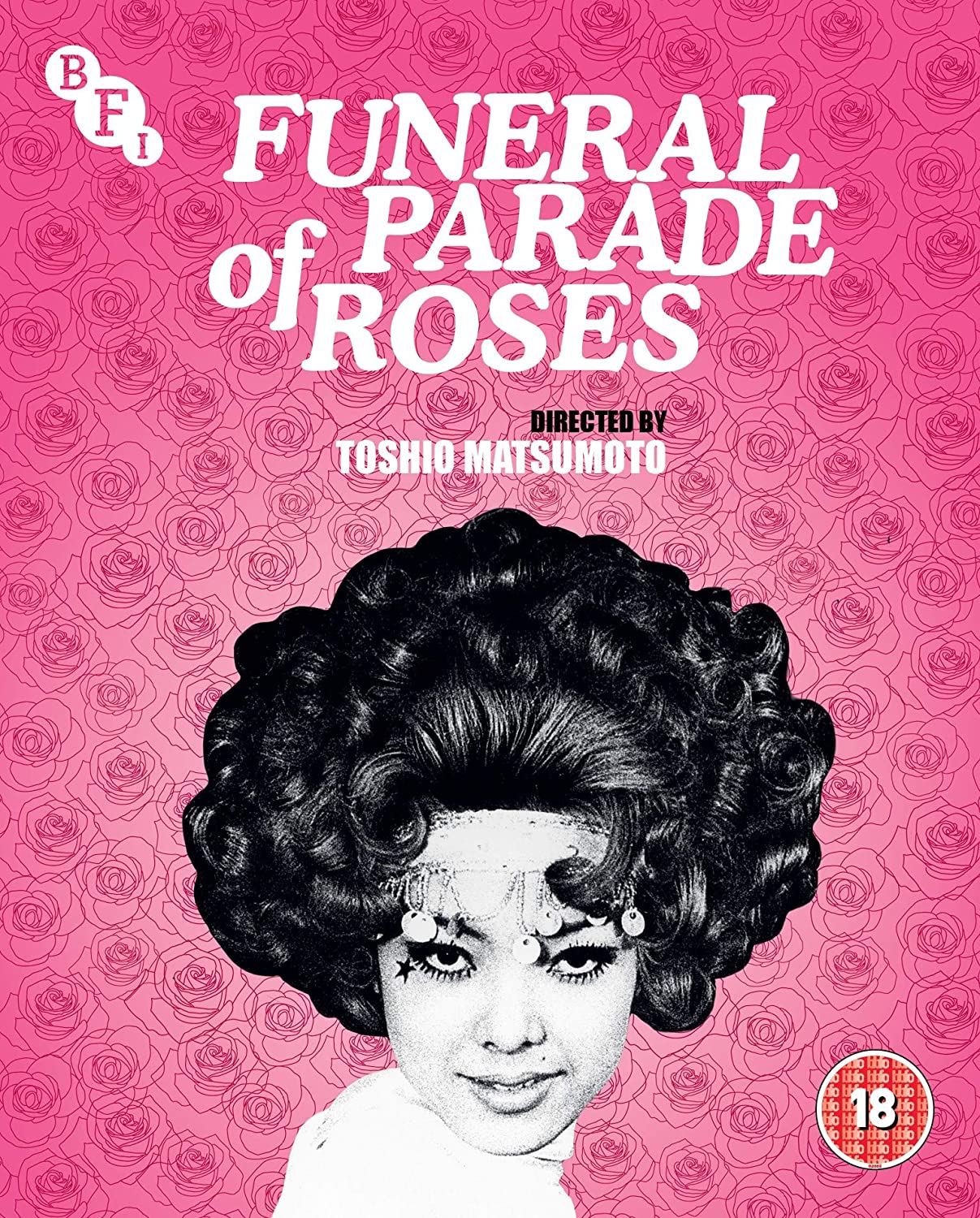

Blu-ray: Funeral Parade of Roses

Blu-ray: Funeral Parade of Roses

A courageous piece from a pioneer of experimental cinema

There is a memorable scene in Toshio Matsumoto’s Funeral Parade of Roses (1969), in which a group of stoned hippies and cross-dressers force each other, one-by-one, to walk the length of a line of tape that runs along the floor. Those who await their turn are seen crouched below, their flailing arms beckoning the walker down from their imagined tightrope. When they fall, as they inevitably and willingly do, they are punished – with the forced removal of their clothes.

This unveiling of the naked body is a symbol for exposure, a metaphor for a film that seeks to shed light on “underground” cultures and narratives. Funeral Parade of Roses is a loose take on Oedipus Rex, following a short but tumultuous period in the life of Eddie, a hostess in one of Tokyo’s underground drag-queen bars. Played by the now-famous but then-unknown Japanese trans actor Pītā, the film enters Eddie into a fatal love-triangle with Madame Leda (Osamu Ogasawara), the bar’s reigning drag-queen, and lover to its male owner, Gonda (Yoshio Tsuchiya). This might not be a world to which Matsumoto belonged, but he is deft enough to avoid its fetishisation; the film's portrayal of the self-identifying “gay boys” is far from uniform. Instead, Funeral Parade of Roses seeks to underline the changing conventions and etiquette within a diverse culture: so, when the austere Leda seeks to condemn her younger and prettier rival, she draws attention to the unprofessionalism of Eddie’s forward and free-spirited sexual behaviour.

But the tightrope scene serves a second function. In staging the violent interruption of its characters’ path, Funeral Parade of Roses enacts the departure of its own recursive discourse from a straightforward linear narrative. Spliced into the main feature are a series of experimental interventions, including documentary-style interviews and film-within-film asides. One scene of Eddie returning with a client from the bar is interrupted with distorted TV images of students battling the kidotai (riot police), a nod to the political and social struggle that shook late-1960s Tokyo. But as if to pinpoint the complex dialogue between cinema and state, the film then cuts again – to another group of students, shown to be recording and reworking the footage for their own means.

These are moves symptomatic of a director who, as an influential figure in the Japanese New Wave, engaged in a subversive overhaul of classical cinema. Borrowing from the example of the Italian avant-garde, Matusmoto's is a work in which, to quote the Lithuanian director Jonas Mekas (as one character in the film does explicitly), “all definitions of cinema have been erased.” Excerpts and flashes from Matsumoto’s host of short films appear, too – the full versions of which, along with an excellent feature-length commentary by film historian Chris. D, and a 34-page booklet of essays that further illuminate the context to the film, number among the special features in the set.

These are moves symptomatic of a director who, as an influential figure in the Japanese New Wave, engaged in a subversive overhaul of classical cinema. Borrowing from the example of the Italian avant-garde, Matusmoto's is a work in which, to quote the Lithuanian director Jonas Mekas (as one character in the film does explicitly), “all definitions of cinema have been erased.” Excerpts and flashes from Matsumoto’s host of short films appear, too – the full versions of which, along with an excellent feature-length commentary by film historian Chris. D, and a 34-page booklet of essays that further illuminate the context to the film, number among the special features in the set.

There is nothing gimmicky about Matsumoto’s radical approach to filmmaking. Fusing light-hearted comedy with abject horror, Funeral Parade of Roses is the equivalent of a wry smile, and a cutting slight against the establishment – both within cinema and without. Upon hearing Leda’s aforementioned complaint, Gonda responds, “You’re encouraging them by saying things like that.” In his creation of this daring and visionary work, the director took those words to heart.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Blu-ray: The Graduate

Post #MeToo, can Mike Nichols' second feature still lay claim to Classic Film status?

Add comment