David Harewood: Psychosis and Me, BBC Two review - actor confronts his painful past | reviews, news & interviews

David Harewood: Psychosis and Me, BBC Two review - actor confronts his painful past

David Harewood: Psychosis and Me, BBC Two review - actor confronts his painful past

The 'Homeland' star explores the mental health crisis he suffered in his twenties

In the week that the Jeremy Kyle show has been yanked permanently off air after the death of one of its vulnerable guests, the timing couldn’t have been better for the BBC to show how sensitively the old-school broadcaster handles contributors with mental health problems.

On Wednesday night, Bake Off star Nadiya Hussain movingly explored her daily struggle with panic attacks without being forced to expose too much detailed information about the childhood traumas which lay at the root of her anxiety disorder. The producers didn’t feel the need to track down and drag onscreen the schoolmates who flushed her head in the toilet for catharsis, preferring instead to follow the presenter talking to therapists and fellow sufferers who gave her advice on talking therapies and medication.

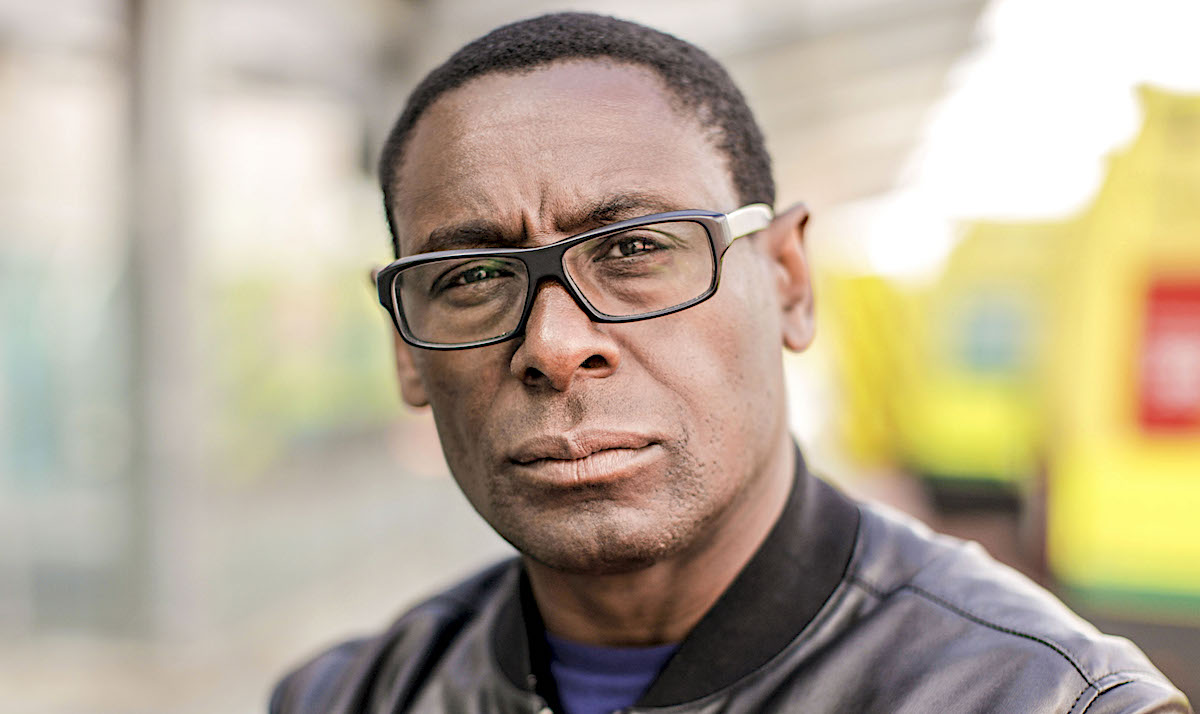

Last night it was actor David Harewood’s turn to unravel the psychotic breakdown he had 30 years ago when his career had just taken off and he was first living in London. Best known for his role in Homeland, it was a brave decision by Harewood to tweet about his mental health crisis two years ago because of the stigma associated with psychosis, and it made the news. Looking back he reflected on how words like “raving loony”, “scary” and “dangerous” leapt to mind when people talked about psychosis. In his case, identity distress about being typecast in the theatre as a black man and oppressed by reading critical reviews of his performances led to manic energy and auditory delusions. At one point, Martin Luther King was giving him instructions on how to save the world.

Harewood was sectioned at the age of 23 in London after his actor friends and flatmates feared for his life. It took six policeman to hold the young actor down while he was sedated and two stays in psychiatric hospitals to help him get better. He’s very honest about how heavy cannabis smoking and alcohol didn’t help him but probably exacerbated the crisis. There was a non-judgmental discussion with psychiatrist Erin Turner about the increased risks of developing severe mental health problems if you’re black British and for anyone who uses strong cannabis under the age of 24.

Harewood couldn’t remember very much about what had happened to him, and there was an element of detective work accessing thirty year old medical files. He read the observations and accounts made when he was sectioned in London and then later spent weeks on a locked psychiatric ward back home in Birmingham.

Harewood couldn’t remember very much about what had happened to him, and there was an element of detective work accessing thirty year old medical files. He read the observations and accounts made when he was sectioned in London and then later spent weeks on a locked psychiatric ward back home in Birmingham.

At times his actorly fluency seemed to desert him, and the disclosed records brought back very painful memories. But there was also joy in his reunion with the two actor flatmates who had got him into hospital and a genuine sense that the process of making the film had helped him understand his past and feel better. Like Nadiya, he also met expert psychiatrists to explain the condition, both to him and the viewer, without too much medical terminology.

A lengthy sequence at an innovative drop-in centre with group therapy for sufferers of psychosis made Harewood feel less alone. It was noticeable that the articulate sufferers interviewed were only identified by their first names in conversation and were in stable mental health, and therefore presumably fully able to give informed consent to being on screen. A sequence in a hospital with a nameless but recognisable woman who had had a psychotic breakdown was more problematic to watch, but showed the grim fallout on her supportive family.

Director Wendie Ottewill made repeated use of visual tropes to convey the powerful delusions that Harewood experienced. Rapid editing of nighttime city images, flashes of scratchy film and faded archive accompanied his voice-over. At times it was over-literal, splitting the screen to present two Harewoods staring at each other when he described a disturbing episode he had when he looked in the mirror. But overall this was a sensitive, thoughtful film which should help dispel the stigma and myths that lurk around psychosis. If only the funding for services and the sympathetic and knowledgeable professionals on display here were available to everyone in the UK who has to deal with mental ill health.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Add comment