10 Questions for Director Ellen McDougall | reviews, news & interviews

10 Questions for Director Ellen McDougall

10 Questions for Director Ellen McDougall

On directing 'Othello' at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, and taking over at the Gate

In a few days' time, Ellen McDougall will become artistic director of the dynamic little Gate Theatre in Notting Hill where she is already an associate artist.

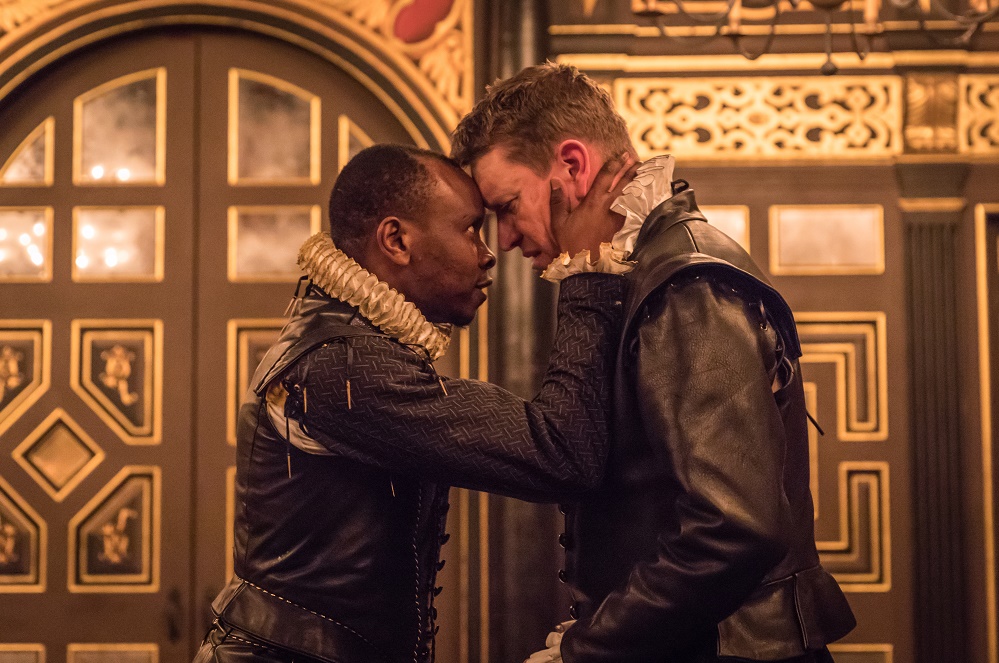

McDougall had considerable success with her playful production of Idomeneus at the Gate in 2014 and was associate director there for two years from 2012. Other acclaimed projects have included The Glass Menagerie for Headlong and Henry V at the Unicorn. After Edinburgh University (where she directed Cymbeline because she enjoyed the challenge) she worked in theatre admin but was soon taking a course in directing at the Young Vic. Known for her bold, original approach and international outlook, she was part of the Secret Theatre Company at the Lyric Hammersmith, received the runner-up prize for the JMK Award 2008 and an Arts Council International Development Award in 2012. She answers theartsdesk's questions by email (pictured below: Kurt Egiawan as Othello and Sam Spruell as Iago).

HEATHER NEILL: Recent productions of Othello have taken the focus off racial difference. For instance, Lucian Msamati was Iago for the RSC and, in the National Theatre's production, Adrian Lester played Othello in a racially mixed group of soldiers. Is Othello's race of primary importance in your interpretation?

HEATHER NEILL: Recent productions of Othello have taken the focus off racial difference. For instance, Lucian Msamati was Iago for the RSC and, in the National Theatre's production, Adrian Lester played Othello in a racially mixed group of soldiers. Is Othello's race of primary importance in your interpretation?

ELLEN McDOUGALL: Yes – it's a play about how prejudice, hate and fear affect the way people behave and think about themselves and other people. It's also a play about identity in lots of ways. Iago's stories have power because they shape the way people see one another – in his central narrative, he defines Desdemona as being a whore. It's about the way words can shape the way we think about people, and devalue them to the point where it's possible to kill them, and racism is part of that narrative.

How will the candle-lit environment of the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse affect the production? Are you, for instance, setting it in period?

It's a really intimate space and I always thought that would be a really good environment for Othello, a play about people's minds, about the intimacy of relationships between people and our fear of being close to one another. The intimacy makes those emotional journeys really available to the audience, and I think the candlelight is part of that. It's also exciting because there are scenes which have been written with a view to being performed with single lit candles, and being able to make people appear and disappear by lighting or extinguishing a candle really helps. (Pictured below: Nadia Albina as Bianca)

Could you give some idea how you approach a classic text. You are said to be especially interested in form. Is that true of your work on Othello?

Could you give some idea how you approach a classic text. You are said to be especially interested in form. Is that true of your work on Othello?

My approach to this classic text has been about what it means to direct a production of this play now, what value this story has to the world now and what questions it might provoke an audience to ask.

Do you have a clear idea of the production in its entirety when you begin rehearsals or do most ideas emerge in working with the actors?

Specific staging ideas emerge with the actors in rehearsals. The themes, questions, and ideas are very thoroughly developed before we start, but the process of rehearsing is another chance to interrogate those ideas and develop and refine them further.

Othello is, famously, a speedy play with events following each other swiftly. Does storyboarding – which you have used in previous productions – help with this?

There are images I wanted to create through the piece that help shape the storytelling. I also work in depth with the dramaturg, Joel Horwood, and the designer, Fly Davis, to consider what the deeper meaning of these images are and how to ensure they speak clearly to the themes we want to draw out. We spent a lot of time thinking about the fascinating structure of this play: for example, Act One is all in Venice, then there is a storm, and a war, and after there is real concern that Othello himself may not survive! When he does, he declares the war is over – and it’s only the start of Act Two. It's interesting to compare it to other Shakespeare plays, where action starts in a court and moves to a forest, for instance, or there is a storm, or a dream, that reshapes a ‘reality’ that has been previously established early on.

Cassio will be played by Joanna Horton (pictured below). On the face of it, this seems daring as Othello regards Cassio as a sexual rival. Does casting a woman in this role bring something new to it or should the audience forget about gender?

The intention is that it brings something new to it, and absolutely reinforces the themes of gender, prejudice, and the construction of identity that are all central to the play. One of the things that disturbs me most about the play is the fact that Othello's final words include "Speak of me as I am" and the Duke says he will go off and tell Othello's story. My experience of the world has taught me not to trust that someone like the Duke will tell his story as Othello has requested.

The intention is that it brings something new to it, and absolutely reinforces the themes of gender, prejudice, and the construction of identity that are all central to the play. One of the things that disturbs me most about the play is the fact that Othello's final words include "Speak of me as I am" and the Duke says he will go off and tell Othello's story. My experience of the world has taught me not to trust that someone like the Duke will tell his story as Othello has requested.

I also realised that the survivors of this story include Iago, the Duke, and Montano – three white men. And Bianca – who is gagged/imprisoned after being accused of Cassio's death, and Cassio, who is severely injured. The idea that history has always been told by the survivors – generally white men – really troubles me in this play that considers so clearly the way our identity is shaped through the stories told about us. I wanted to find a way to respond to this. A way to imagine something more than just a cycle of repeated white patriarchal narratives. One of the things about a female Cassio means there are two survivors at the end who are women who fight for truth, and who find love in a brutal world. One of my answers to the question I asked, "Why do this play now?", was in some way answered by this image.

What did you learn from taking part in the Lyric Hammersmith's Secret Theatre?

It encouraged me to not be afraid to take risks, to support an atmosphere based on an ensemble having creative agency within a rehearsal room, to play to the strengths of different people within an ensemble. We spent a long time rehearsing the first two plays and we made big interventions into the way we were presenting those plays. That taught me a lot about dramaturgy and how you can tell a story visually as much as with the text. It was also the first time I'd worked with Joel Horwood as dramaturg, and I discovered that collaborating with a writer who isn’t the author of the text you are working on gives a brilliant dimension to the development of ideas through the creative process.

When it comes to my own work, parity and diversity make for a better conversation and a more rigorous interrogation of the play, because you're looking at it from as many different points of view as possible

You take over as Artistic Director of the Gate Theatre in Notting Hill next month. What are you hoping to achieve there?

I want the Gate to be a place where brilliant theatremakers who are unafraid of taking risks from all around the world can come and do that. I want it to be a place where the most diverse range of artists get to come together, challenge one another and be inspired by one another. I want to build on the Gate’s role within the UK theatre ecology as a place where you can go to see adventurous, dangerous theatre that always confounds expectations.

Is it a bonus that it is an intimate space?

Yes. It means that there are enough people that you feel like an audience but it's small enough that you feel like you have a relationship with everyone else in the room, like you're a group of people watching something together. That feels to me like what the heart of theatre is about; a communal experience of watching something live together. It also means it's impossible to ever feel separated from the action, which I think is really exciting. It's similar to working in the Sam Wanamaker, it feels like we're in one room telling the story and we're all participating in it, whether we're watching or performing it.

Your mentors have often been women directors. You attended a course run by Indhu Rubasingham, have assisted Katie Mitchell and Marianne Elliott and have been encouraged by Purni Morell, first at the NT Studio and then at the Unicorn, where you directed an acclaimed Henry V for children. Do you see it as important that you are a woman being appointed to run a theatre?

Yes. If we want to exist in a world that puts equality and diversity at the heart of the way we treat one another and see one another, then it's a given that at every level of running any institution, there must be the widest possible range of people involved.

When it comes to my own work, parity and diversity make for a better conversation and a more rigorous interrogation of the play, because you're looking at it from as many different points of view as possible. If everyone has a similar background and experience of the world then you'll get a singular understanding of that play, which is not going to talk to the experience of what is hopefully a diverse audience.

You have said that you will continue to work with international directors and playwrights in future, this being "more important than ever". No doubt this is in the light of the Brexit referendum result and some of President Trump's divisive policies. Has theatre an especially important political role to play just now?

I think theatre's always had a political role. At its most basic, it's bringing people together to imagine a story, to empathise with a character and see themselves in that narrative, or to question their own way of being in the world. If we're talking about just now, we're talking about a world that's increasingly fearful of difference, and driven by people who want to divide us rather than bring us together. At its most basic theatre is doing the opposite of that. Theatre isn't necessarily going to change the world on its own, but it can nurture a changing world. It can make us think differently about each other, which is where change can start.

- Othello at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse until 22 April

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Add comment