All's Well That Ends Well, Tobacco Factory, Bristol | reviews, news & interviews

All's Well That Ends Well, Tobacco Factory, Bristol

All's Well That Ends Well, Tobacco Factory, Bristol

A Shakespeare 'problem play' made good

Andrew Hilton’s new production of All’s Well That Ends Well makes the most of the complexities of a "problem play", neither comedy nor tragedy, and navigates this startling mix of emotional depth and light farce with great deftness.

This is Shakespeare as master trickster, playing with narrative genres, the tricks of his characters matching the sleight of hand and suspension of disbelief displayed in a story that combines the simple manicheism and magic of fairy tale with the realities of gender politics, reflections on the inconstancy of human nature and the inifinite and sometimes deceptive malleability of language. Hilton juggles these disparate elements – those very things that can so easily turn this problem play into a mess – with a lightness of touch that is at times breathtakingly magical.

There is a war here, not just between kingdoms, but between the sexes

He has chosen his actors well: the regular members of the company surpass themselves, from Chris Bianchi as the King of France, the depressed and wounded monarch near-miraculously reborn and rejuvenated thanks to the scheming intervention of low-born Helena, to Paul Currier (pictured below) who brings a touch of genius to the almost Ubu-esque absurdity of Parolles, displaying a convincing range of emotion – from arrogant bluster to pathetic vulnerability. Ian Barritt’s Lafew provides a perfect comic foil to the play’s overdressed buffoon, displaying a different variation on the theme of pathetic and self-aggrandizing pomp.

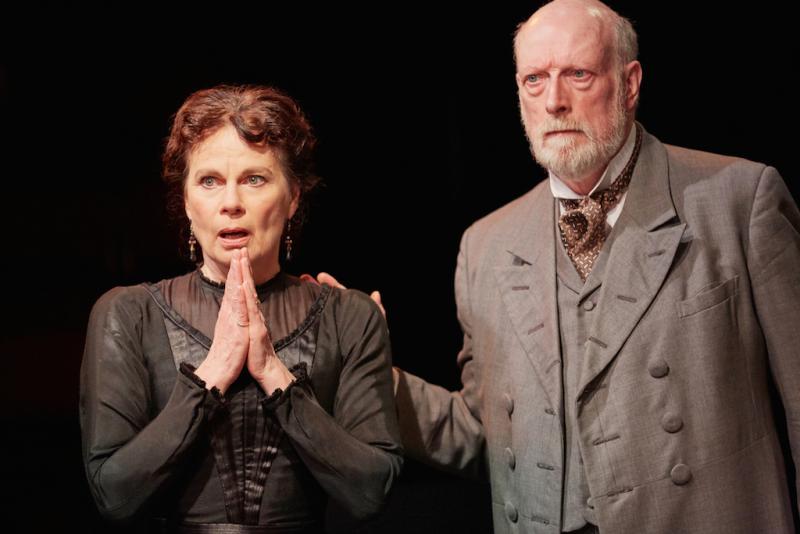

Julia Hills evokes in the Countess a full and constantly shifting range of emotions, as she reacts to the twists and turns of the story. Not just the loving mother, whose affections are buffeted by fate, she is also the whirlwind narrative’s grounding anchor, and her interpretation supports the play’s central defense of women in the face of misogyny. The female characters in the play are all strong – the men are definitely the weaker sex here – and Eleanor Yates (Helena) manages admirably well a winning and delightful combination of soft sensitivity and war-like strength and determination.

There is a war here, not just between kingdoms, but between the sexes. The play’s most evident potential weakness lies in the recurring metaphorical fun around the ideas of conquest and virginity, first set forth in Parolles’s monologue. And yet the metaphor is worn lightly, as a comic leitmotiv, all the more so because of this production’s unerring pace, strongly cohesive ensemble performance, and perhaps most importantly, the comedy show complicity afforded by the Tobacco Factory’s full 360 degrees seating arrangement.

The most difficult role in this morally intricate play is that of Bertram, the young Count on the make, beloved of Helena, and yet set on a more socially elevated wife. Craig Fuller captures the almost one-dimensional adolescence of the character well: he is both callow and cold, and most of all unformed. The play is, on one level, the story of his transformation and coming of age. The agents of this change are multiple: not least the constancy and wiles of Helena who sets her heart on winning him as a husband, but also the sight, it would seem, of Parolles’s undoing, his pretense and pride savagely deconstructed by Bertram’s male acolytes, who kidnap the unfortunate clown and sadistically play with his essential insecurity.

The most difficult role in this morally intricate play is that of Bertram, the young Count on the make, beloved of Helena, and yet set on a more socially elevated wife. Craig Fuller captures the almost one-dimensional adolescence of the character well: he is both callow and cold, and most of all unformed. The play is, on one level, the story of his transformation and coming of age. The agents of this change are multiple: not least the constancy and wiles of Helena who sets her heart on winning him as a husband, but also the sight, it would seem, of Parolles’s undoing, his pretense and pride savagely deconstructed by Bertram’s male acolytes, who kidnap the unfortunate clown and sadistically play with his essential insecurity.

The magic of Hilton’s emotional intelligence becomes clearest as the play unfolds towards what might seem on the surface a simplistic happy end. There is a great deal of undoing towards the end of the story: Lavatch – a great comic turn from Marc Geoffrey as a slightly camp and uptight singing and dancing master – has a major wobbly and temporarily loses his mind, and Parolles’s assumed grandeur is cut down to humble size. It is at this very moment that Bertram begins to grow up, to move from a cardboard cut-out attempt at virility to the possibility of mature love. Fuller communicates this shift in heart and attitude in a tangible and convincing way.

There is undeniable irony in the play’s title and its allusion to the happy end we crave for in real life, as well as on the stage. The final dance, choreographed with elegance by Lavatch, who has regained his balance, moves from a stately promenade to a whirling waltz – a moment which evokes with delicious melancholy the dizzying inconstancies of existence, the illusions we live by, and that make the beguiling magic of theatre possible.

- All's Well That Ends Well is at the Tobacco Factory until 30 April and then tours the UK from 3 May - 18 June

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Comments

Bertram is played by Craig

Bertram is played by Craig Fuller....you might want to amend the post.