Grayson Perry: Who Are You?, Channel 4 | reviews, news & interviews

Grayson Perry: Who Are You?, Channel 4

Grayson Perry: Who Are You?, Channel 4

Engaging series about portraiture in action captures subjects at a crossroads

The night before he was locked up, Chris Huhne had that Grayson Perry round for tuna steaks. Who knew? Perry was embarking on a series of portraits about identity at a crossroads, and can there be a more public crisis of identity than a Cabinet minister going to prison? But first Perry wanted to get to know his subject. Huhne was resistant to probing.

Perry’s theory of the portrait is that a good one “tells you something a thousand selfies never could”. A portraitist is somewhere between a psychologist and a detective, he explained, charged with exposing an inner truth lurking behind the mask. It sounds plausible, even if the exception that proves the rule is the most famous portrait of all: we know nothing at all about Mona Lisa’s emotional hinterland.

Huhne is the banner headline of Perry’s series about portraiture in action. Perry’s other subjects in this first episode will be of less interest to the tabloids but are in other ways more intriguing: Rylan Clark, a tissue-thin creation of the modern celebrity culture who seems to have no discernible personality at all; a young white British Muslim convert called Kayleigh; and Jazz, who grew up as a girl and is now undergoing gender reassignment.

Huhne is the banner headline of Perry’s series about portraiture in action. Perry’s other subjects in this first episode will be of less interest to the tabloids but are in other ways more intriguing: Rylan Clark, a tissue-thin creation of the modern celebrity culture who seems to have no discernible personality at all; a young white British Muslim convert called Kayleigh; and Jazz, who grew up as a girl and is now undergoing gender reassignment.

This series is partly a portrait of a modern Britain formerly dominated by white, middle-class, middle-aged males but now undergoing an identity crisis of its own. We all know the place isn’t what it was. Why, nowadays a transvestite potter can get a CBE, deliver the Reith lectures and run amok in the British Museum and, for this series, the National Portrait Gallery. That said, the first episode is slightly less representative of our cultural fluidity than it thinks it is. All the sitters were from the south-east, and all but one in their twenties.

Perry is an artful interviewer but he was clearly less than interested in the frightened little boy lurking behind Clark's fictitious, mediated construct. Meanwhile his teasing, matey style of interrogation could do nothing to unlock Huhne, who rather thought that he had something in common with Saint Sebastian. An odd comparison. Renaissance canvases graphically remind us that this was a martyr who, unlike Huhne, took his points. Three months inside did nothing to dent his ironclad self-image.

Perry also knows when to keep out of the way and watch. He was rewarded with the sight of Kayleigh, a former teenage tearaway, justifying her conversion to Islam. “Wiv Allah,” she explained, “He knows everyfink.” She asked her four well-behaved/brainwashed kids if they agreed. They nodded their heads. Her brother was less persuaded: “You can’t eat pork, you can’t drink, you can’t smoke. You’ve got to have kids after marriage.” As 5,000 Brits convert to Islam every year, expect more of these Socratic dialogues.

Much the most thoughtful part of the film focussed on Jazz, who is still a “she” to his mum. There was a moving interview with the latter, and a remarkable group discussion between Jazz and a group of school pupils about the pressures of society to conform to media-promoted notions of gender and sexual identity.

Much the most thoughtful part of the film focussed on Jazz, who is still a “she” to his mum. There was a moving interview with the latter, and a remarkable group discussion between Jazz and a group of school pupils about the pressures of society to conform to media-promoted notions of gender and sexual identity.

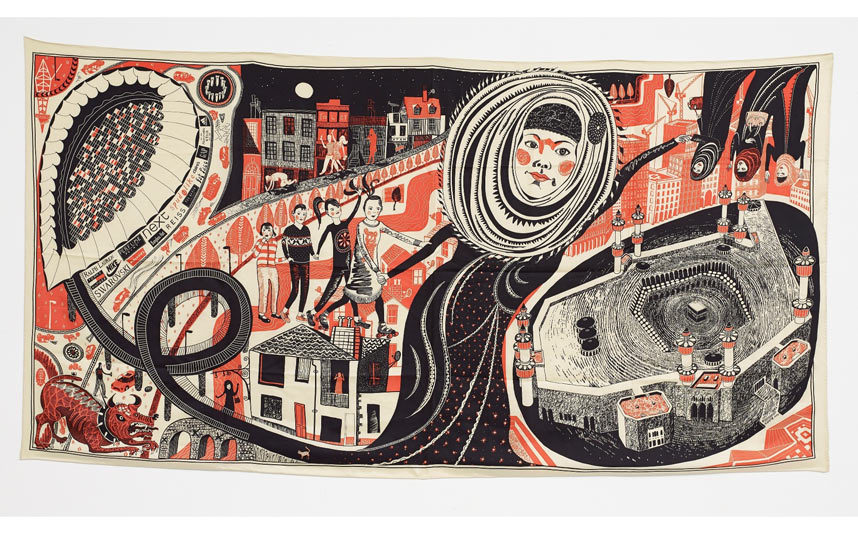

In what he called "the ongoing lifelong artwork that is our individual identity", Perry had most invested in this story. And it showed when, for the climax, the sitters were all introduced to their own likeness at the National Portrait Gallery. Jazz (now called Alexander) was portrayed as a Benin-style statue of a trumpeting warrior hero. “I wanted my portrait to help him on his way," said Perry. Clark got a modern Elizabethan miniature, Kayleigh a hijab depicting her transformation (pictured above). However chuffed, only Huhne didn't seem instinctively to recognise his personal trajectory in the image of a Grecian urn that had been smashed and put back together again. But he took a selfie anyway.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment