Timon of Athens, National Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Timon of Athens, National Theatre

Timon of Athens, National Theatre

A consistently intelligent staging of a tricky play which offers no hope

As the much-loved Arthur Marshall so profoundly noted, Ibsen is “not a fun one”. One could, with as much truth, say the same about Shakespeare’s rarely staged Timon of Athens: its misanthropy, missing motivations and mercurial shifts in temper do not spell a fun night out to most. It is greatly to the credit of director Nicholas Hytner and his team, therefore, that the evening, if it doesn’t exactly fly by, is consistently engaging, thought-provoking and downright intelligent.

Hytner and his designer, Tim Hatley, have created a world that mirrors our own. Timon is officially “of Athens”, but here we begin at a private party celebrating the opening of “The Timon Room”, named for a museum’s generous benefactor. Yet even as the sycophants and money-men hover over the evening’s Maecenas, the room itself is presided over by an El Greco: Christ Turning the Moneylenders Out of the Temple.

Timon’s adoring “friends” praise him to each other as “the God of kindness”, the “noblest mind”, even as they segue into commending his wealth as the representation of that kindness and nobility.

The problem with the play (which Shakespeare, possibly collaborating with Middleton, seems to have abandoned, and which may never have been performed), is that Timon has no interior life – there is, as Gertrude Stein said (about Oakland, as it happens, but never mind), “no there there”. We have no idea where Timon’s money came from; we don’t know anything about his family, his private life, his ideas, thoughts, what drives his profligacy, his almost manic generosity. When, therefore, he loses all and rejects the world, we cannot feel that a great man has been destroyed: he is simply a vacuum.

The problem with the play (which Shakespeare, possibly collaborating with Middleton, seems to have abandoned, and which may never have been performed), is that Timon has no interior life – there is, as Gertrude Stein said (about Oakland, as it happens, but never mind), “no there there”. We have no idea where Timon’s money came from; we don’t know anything about his family, his private life, his ideas, thoughts, what drives his profligacy, his almost manic generosity. When, therefore, he loses all and rejects the world, we cannot feel that a great man has been destroyed: he is simply a vacuum.

Timon, unusually (and possibly merely because of its uncertain performing history), is not entitled by Shakespeare "The Tragedy of…", but only "The Life of...". For, truly, there can be no tragedy for a man with no interiority. What is it that makes Timon break when he is betrayed by his so-called friends, to go from manic giving to equally manic hatred for the world? Simon Russell Beale as Timon pulls all that is possible, and more, from this part – his gentle, almost tender verse-speaking draws every possibility out of the morass of curses that defines the second act of the play; his very physicality shifts between the giving and the rejecting.

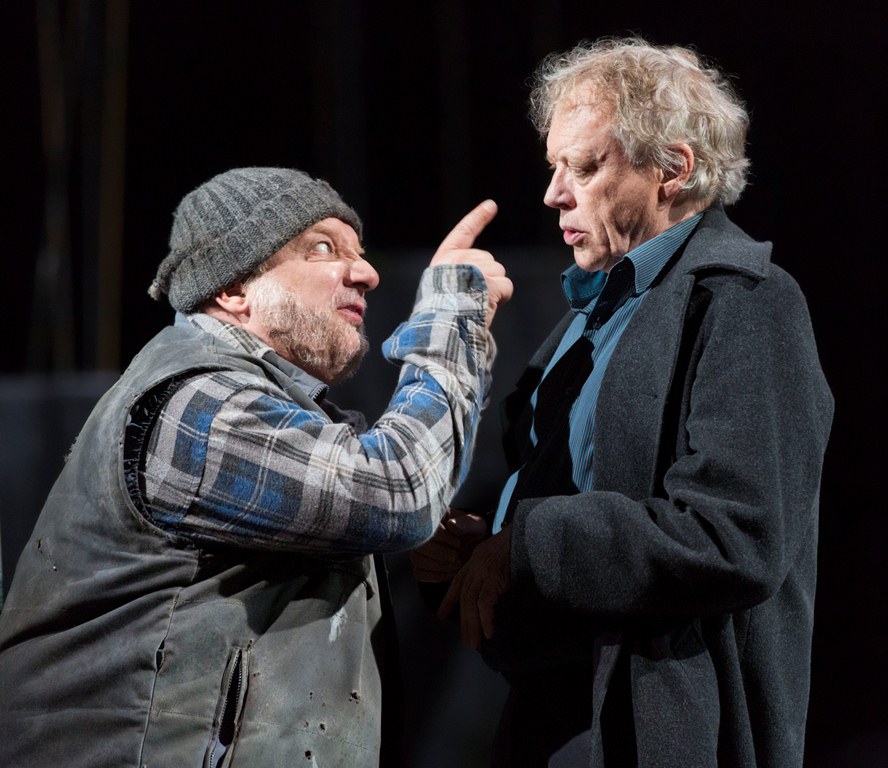

He is well-matched, too, by those fine performers Deborah Findlay as the steward, written by Shakespeare as Flavius, here become Flavia, and Hilton McRae as the cynical philosopher Apemantus (pictured left with Russell Beale). Apart from their individual performances, they are unusually well paired: Findlay’s devotion is expressed entirely as generous affection, while McRae’s fondness is given a sterner distance and demeanour. The scene where Apemantus and Timon spar amid the dereliction of the homeless encampment is a pairing of equals as despair, comic cynicism and competitive cursing flicker back and forth between the two men.

He is well-matched, too, by those fine performers Deborah Findlay as the steward, written by Shakespeare as Flavius, here become Flavia, and Hilton McRae as the cynical philosopher Apemantus (pictured left with Russell Beale). Apart from their individual performances, they are unusually well paired: Findlay’s devotion is expressed entirely as generous affection, while McRae’s fondness is given a sterner distance and demeanour. The scene where Apemantus and Timon spar amid the dereliction of the homeless encampment is a pairing of equals as despair, comic cynicism and competitive cursing flicker back and forth between the two men.

Given its ragged nature, Hytner has done well to ground the play by reflecting our own world back at us, a world where the only unforgiveable act is to be poor. Alcibiades, the rebel leader (a good performance, too, from Ciarán McMenamin), leads the equivalent of the Occupy Wall Street forces, who catcall “Shame on you” (as they do not in the original). Outside is Belgravia stucco, steel-and-glass City, sandstone Gothicised parliament.

And finally we watch as ultimately Alcibiades too sells out. Hytner, Hatley, and Shakespeare allow us no hope: the money-changers will not be turned out of the temple, they say. It is not that easy.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Wendy & Peter Pan, Barbican Theatre review - mixed bag of panto and comic play, turned up to 11

The RSC adaptation is aimed at children, though all will thrill to its spectacle

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

Hedda, Orange Tree Theatre review - a monument reimagined, perhaps even improved

Scandinavian masterpiece transplanted into a London reeling from the ravages of war

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

The Assembled Parties, Hampstead review - a rarity, a well-made play delivered straight

Witty but poignant tribute to the strength of family ties as all around disintegrates

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Mary Page Marlowe, Old Vic review - a starry portrait of a splintered life

Tracy Letts's Off Broadway play makes a shimmeringly powerful London debut

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

Little Brother, Soho Theatre review - light, bright but emotionally true

This Verity Bargate Award-winning dramedy is entertaining as well as thought provoking

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Unbelievers, Royal Court Theatre - grimly compelling, powerfully performed

Nick Payne's new play is amongst his best

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

The Maids, Donmar Warehouse review - vibrant cast lost in a spectacular-looking fever dream

Kip Williams revises Genet, with little gained in the update except eye-popping visuals

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review - compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit 'Farm Hall'

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Add comment