The Battleship Potemkin Comes Out of the Closet | reviews, news & interviews

The Battleship Potemkin Comes Out of the Closet

The Battleship Potemkin Comes Out of the Closet

Sexual and political mutiny emerges in cinema restoration of the silent masterpiece

When Sergei Eisenstein's film The Battleship Potemkin was first shown in Moscow in December 1925, just in time to commemorate the 1905 Revolution, the film played to half-empty theatres, because audiences, then as now, preferred the products from Hollywood. Box-office figures were exaggerated by the authorities to demonstrate to the rest of the world that there was a large Soviet audience for Soviet films.

The Battleship Potemkin's depiction of a (partially) successful rebellion against political authority disturbed the world's censors. The French, banning it for general showing, burned every copy they could find. It was shown only in film clubs in London, where it had been banned. Initially in the USA it was forbidden on the grounds that it "gives American sailors a blueprint as to how to conduct a mutiny". In Germany the War Ministry forbade members of the armed forces to see the film. A few years later, after Stalin came to power in the USSR, a written introduction by Leon Trotsky was removed by the Soviets and replaced by a quotation from Lenin.

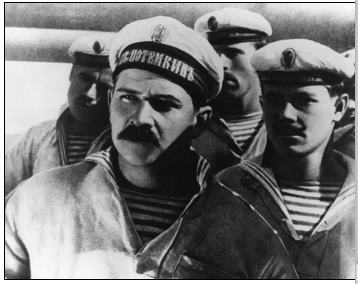

However, the one aspect of The Battleship Potemkin that has never aroused any censorship is Eisenstein's mischievous homoeroticism, which is evident to modern audiences more than ever. Many critics (not all of them gay) have cited the homoerotic images in his films. The gay American film writer Parker Tyler wrote, "Eisenstein has a great personal eye for human beauty, and more especially for male beauty." Predictably The Battleship Potemkin, with its sailors (regular figures in gay iconography), has provided much material for proof of Eisenstein’s homosexuality (Eisenstein pictured below).

I n the 1980s, Nestor Almendros, the exiled Cuban cinematographer, wrote: "Potemkin has been considered a revolutionary film not only because of its subject, but also for its treatment and because it departed in its structure from conventional bourgeois drama – the eternal love affair between a man and a woman.

n the 1980s, Nestor Almendros, the exiled Cuban cinematographer, wrote: "Potemkin has been considered a revolutionary film not only because of its subject, but also for its treatment and because it departed in its structure from conventional bourgeois drama – the eternal love affair between a man and a woman.

"Its absence from Potemkin was attributed solely to Eisenstein’s pristine concentration on the social forces governing society according to Marx. Yet there is evidence to support another hypothesis. The absence of a conventional love affair (as in all Eisenstein’s work) could result from the fact that there was very little space for women in his world. Sexuality as an added theme would only cloud the main issues. The trouble is that Potemkin is not asexual but very sexual – homoerotic. From its very beginning, with the sailors' dormitory prologue, we see an 'all-male cast' resting shirtless in their hammocks. The camera lingers on the rough, splendidly built men, in a series of shots that anticipate the sensuality of Mapplethorpe, and at the great moment when the cannons are raised to fire, a sort of visual ballet of multiple slow and pulsating erections can easily be discerned."

Although subjective, Almendros and other gay commentators cannot be accused of special pleading. Eisenstein was a self-confessed phallic obsessive. Knowing this, it is not unlikely that he was slyly playing with the slowly rising guns as well as the scenes with sailors polishing pistons in a masturbatory manner. There are also the fleeting shots of two sailors obviously kissing as the cannons rise.

Although subjective, Almendros and other gay commentators cannot be accused of special pleading. Eisenstein was a self-confessed phallic obsessive. Knowing this, it is not unlikely that he was slyly playing with the slowly rising guns as well as the scenes with sailors polishing pistons in a masturbatory manner. There are also the fleeting shots of two sailors obviously kissing as the cannons rise.

There is a particular homoerotic image that appealed to Eisenstein. After the killing of the leader of the mutiny, "a young lad tears his shirt in a paroxysm of fury" revealing his bare chest. (Actually it could also be read as the ancient Jewish tradition of tearing one’s clothes in mourning.) This derived from Eisenstein’s reading of reports about a young man who, during the 1917 revolution in St Petersburg, had his shirt torn off his back before being executed – "His perforated body lay on the granite steps, half-submerged in the Neva… the two halves of the boy’s shirt lying on the granite steps near the Sphinxes of the Egyptian Bridge."

Revealingly, Eisenstein admits that he was more interested in the section with the boy tearing his shirt than the hoisting of the red flag at the film’s finale. The motif reoccurs in Ivan the Terrible, when the Tsar’s would-be assassin, a young monk, has his shirt torn off him.

It was in the sketches that Eisenstein drew in Mexico in 1931 that his often regressive phallophilia reached its peak. During the shooting of the unfinished Que viva México!, Eisenstein found time to make many of his finest erotic drawings. The drawings as well as photos of nude males were found in the trunks and boxes Eisenstein sent to Hollywood from Mexico and were seized by US Customs agents, causing a scandal. It was also from Mexico that he sent his English friend Ivan Montague the well-known photograph of himself perched on a gigantic bulbous cactus plant, which seemingly protrudes from between his legs, with the words, "Speaks for itself and makes people jealous."

Andrei Koncholovsky remembers being told by his mother, who was a friend of Eisenstein’s, that he had shown her drawings he had made of a number of penises, in different postures, with faces drawn on them – a giant, a fat bourgeois, a sportsman, a dwarf – happy and erect or sad and drooping, small or large, in fact many of the characters from his films were all there in synecdochic form.

Then there is the phallic and ejaculatory exclamation mark that appears at the tail of many of his sentences and inter-titles. Given Eisenstein’s explosive, revolutionary nature, he could have been one of the few people to put an exclamation mark after his name. This is not as fanciful a notion as it sounds. Eisenstein never missed an opportunity to make such analogies no matter how bizarre. During a lecture on the shape of the screen, given to the Technicians Branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Hollywood in 1930, Eisenstein declared, “It is my desire to intone the hymn of the male, the strong, the virile, active, vertical composition! I am not anxious to enter the dark phallic and sexual ancestry of the vertical shape as a symbol of growth, strength or power. It would be too easy and possibly too offensive for many a sensitive listener! But I do want to point out that the movement towards the vertical perception launched our hirsute ancestors on their way to a higher level."

Then there is the phallic and ejaculatory exclamation mark that appears at the tail of many of his sentences and inter-titles. Given Eisenstein’s explosive, revolutionary nature, he could have been one of the few people to put an exclamation mark after his name. This is not as fanciful a notion as it sounds. Eisenstein never missed an opportunity to make such analogies no matter how bizarre. During a lecture on the shape of the screen, given to the Technicians Branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in Hollywood in 1930, Eisenstein declared, “It is my desire to intone the hymn of the male, the strong, the virile, active, vertical composition! I am not anxious to enter the dark phallic and sexual ancestry of the vertical shape as a symbol of growth, strength or power. It would be too easy and possibly too offensive for many a sensitive listener! But I do want to point out that the movement towards the vertical perception launched our hirsute ancestors on their way to a higher level."

In Esquire magazine, Dwight Macdonald was disturbed by Ivan the Terrible, the director’s final masterpiece. "Eisenstein’s homosexuality now has free play… There are an extraordinary number of young, febrile and – there’s no other word – pretty males, whose medieval bobbed hair makes them look startlingly like girls. Ivan has a favourite, a flirtatious, bold-eyed police agent, and many excuses are found for having Ivan put his hands on the handsome young face… There are two open homosexuals in the film, both villains. The minor one is the King of Poland, who is shown in his effete court camping around in a fantastically huge ruff… the major one is the very odd character of Vladimir… It is too much to speculate that Eisenstein identified himself with the homosexual Vladimir, the helpless victim of palace intrigues who just wanted to live in peace (read: to make his films in peace…)"

It is extremely doubtful that Eisenstein, in that he identified with any character in the film, would have chosen the simple-minded, cowardly and effeminate Vladimir. Parker Tyler describes Vladimir as "pretty as a Hollywood starlet… constantly pursing his lips or batting his eyelashes…" Andrew Britton described the scene between the traitor Kurbsky and Sigismond, the King of Poland, as "decadent homosexual flirtation, Kurbsky presenting his sword and Sigismond stroking it languidly with jewelled gloves".

It is extremely doubtful that Eisenstein, in that he identified with any character in the film, would have chosen the simple-minded, cowardly and effeminate Vladimir. Parker Tyler describes Vladimir as "pretty as a Hollywood starlet… constantly pursing his lips or batting his eyelashes…" Andrew Britton described the scene between the traitor Kurbsky and Sigismond, the King of Poland, as "decadent homosexual flirtation, Kurbsky presenting his sword and Sigismond stroking it languidly with jewelled gloves".

Was Eisenstein really planting a clandestine gay time bomb under a perilously homophobic society?

Somehow, Eisenstein’s "gayness" escaped the censorious eye of Stalin, nor did he ever become a victim of the overt anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union, although he considered himself to have only an eighth of Jewish blood. Suspect comrades were often referred to pejoratively as "cosmopolitans". Riga, the city where he was born, had a fairly large Jewish community. Both in Latvia and Lithuania, the Jews were treated as equals under the law. In Odessa, however, whose population was 30 per cent Jewish, countless Jews were slaughtered in the streets in 1905 in one of the most terrible pogroms in Russian history, the sort of pogrom that must have driven Eisenstein’s paternal grandparents to give up their Jewish heritage. But in The Battleship Potemkin, when the sneering bourgeois says, "Down with the Jews", the proletarian population react violently to this remark and attack the man.

This sequence was obviously influenced by Eisenstein’s friend, the Jewish writer Isaac Babel. While Eisenstein was writing the script of Potemkin, he was simultaneously working with Babel on a script of The Career of Benja Krik, based on the latter’s story in Tales of Odessa. There is a further link with Babel, who wrote the inter-titles for a Yiddish film called Jewish Luck, made the year before Potemkin, which has a dream sequence shot on the Odessa steps!

Eisenstein’s sublimated homosexuality and Jewishness, which partly explains his "cosmopolitanism", in the objective sense, and his detachment from the mainstream of Soviet artists, only adds another layer to the continuing fascination of his oeuvre and particularly The Battleship Potemkin. In the latter, Eisenstein's method is one of collision, conflict and contrast, with the emphasis on a dynamic juxtaposition of individual shots that forces the audience consciously to come to conclusions about the interplay of images while they are also emotionally and psychologically affected. The 80-minute Battleship Potemkin contains 1,346 shots, whereas the average film around 1926 ran 90 minutes and had around 600 shots.

Eisenstein’s sublimated homosexuality and Jewishness, which partly explains his "cosmopolitanism", in the objective sense, and his detachment from the mainstream of Soviet artists, only adds another layer to the continuing fascination of his oeuvre and particularly The Battleship Potemkin. In the latter, Eisenstein's method is one of collision, conflict and contrast, with the emphasis on a dynamic juxtaposition of individual shots that forces the audience consciously to come to conclusions about the interplay of images while they are also emotionally and psychologically affected. The 80-minute Battleship Potemkin contains 1,346 shots, whereas the average film around 1926 ran 90 minutes and had around 600 shots.

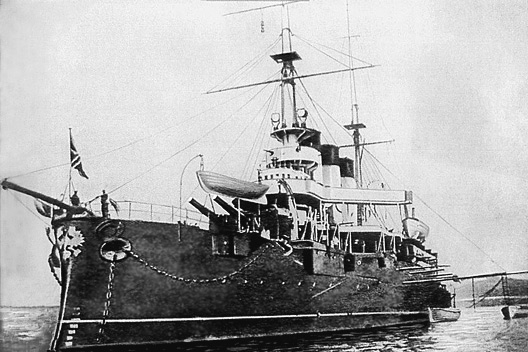

But these dry statistics fail to convey the impact of the shots and what they contain. It is well to be reminded that Potemkin presents flesh-and-blood characters and also tells an exciting story (the real Battleship Potemkin pictured below, its Tsarist crest on the prow).

The film starts below deck in the humid sleeping quarters, with its labyrinth of hammocks, heavy with bodies gently swinging. The oscillating motion is later repeated by the pendulous metal tables laden with uneaten bowls of soup. The scene transmits a faint but unmistakable echo of Charlie Chaplin struggling to eat on a similar table in The Immigrant, the kind of analogy to which Eisenstein was never averse. "In the encounter with the squadron, the machines were almost like the heart of Harold Lloyd, jumping out of his waistcoat because it was so agitated," he wrote of the film’s final sequence.

The film starts below deck in the humid sleeping quarters, with its labyrinth of hammocks, heavy with bodies gently swinging. The oscillating motion is later repeated by the pendulous metal tables laden with uneaten bowls of soup. The scene transmits a faint but unmistakable echo of Charlie Chaplin struggling to eat on a similar table in The Immigrant, the kind of analogy to which Eisenstein was never averse. "In the encounter with the squadron, the machines were almost like the heart of Harold Lloyd, jumping out of his waistcoat because it was so agitated," he wrote of the film’s final sequence.

Nevertheless, everything seems to swirl around the central maelstrom that is universally known as the "Odessa Steps sequence", against which the whole of cinema can be defined before and since. It is surprising that the sequence, having probably been anatomised more than any other, is still as robust as ever. The sequence works on many levels, the formalistic, linked to Marxist dialectics, force (thesis) colliding with counter-force (antithesis) to produce unity (synthesis).

[bg|/FILM/jasper_rees/Potemkin]

Here are human beings – a legless man rushing to escape, an elderly woman teacher shot in the face, a nursemaid shot in the stomach, leaving her charge in the pram unattended (the suspense of this moment, the pram poised to topple, is positively Hitchcockian), a doctor administering to the wounded, a bespectacled student helplessly regarding the scene in horror, civilians cowering in terror beneath the steps and a mother carrying her dead child towards the advancing soldiers in a plea for mercy in a sudden poignant counterpoint to the main flow of the crowd.

It has even more impact because we have already seen these people in a euphoric state before the massacre. As a graphic illustration of state brutality "The Odessa Steps Sequence" is worthy of comparison with Desastros de la Guerra by Goya, one of Eisenstein’s favourite artists, and Picasso’s Guernica.

- The Battleship Potemkin in a new full restoration with its original Edmund Meisel score re-recorded, is shown at the BFI 29 April-12 May as part of the BFI Russian season

Find Ronald Bergan's most recent book Isms: Understanding Cinema (Universal) on Amazon

Find Ronald Bergan's most recent book Isms: Understanding Cinema (Universal) on Amazon Find The Battleship Potemkin on DVD on Amazon

Find The Battleship Potemkin on DVD on Amazon

*The title of the film has tended to a literal translation since the Russian language takes no article – neither definite or indefinite. However, languages which do take articles, such as French, have rendered titles correctly for their own languages eg La Cuirassé Potemkin. The Battleship Potemkin is the correct English translation as we would say The Queen Elizabeth for the ship, and Queen Elizabeth for the person.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

Late Shift review - life and death in an understaffed Swiss hospital

Petra Volpe directs Leonie Benesch in a compelling medical drama

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

The Naked Gun review - farce, slapstick and crass stupidity

Pamela Anderson and Liam Neeson put a retro spin on the Police Squad files

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Lars Eidinger on 'Dying' and loving the second half of life

The German star talks about playing the director's alter ego in a tormented family drama

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

The Fantastic Four: First Steps review - innocence regained

Marvel's original super-group return to fun, idealistic first principles

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

Dying review - they fuck you up, your mum and dad

Family dysfunction is at the heart of a quietly mesmerising German drama

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

theartsdesk Q&A: director Athina Rachel Tsangari on her brooding new film 'Harvest'

The Greek filmmaker talks about adapting Jim Crace's novel and putting the mercurial Caleb Landry Jones centre stage

Blu-ray: The Rebel / The Punch and Judy Man

Tony Hancock's two film outings, newly remastered

Blu-ray: The Rebel / The Punch and Judy Man

Tony Hancock's two film outings, newly remastered

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire review - a mysterious silence

A black Caribbean Surrealist rebel obliquely remembered

The Ballad of Suzanne Césaire review - a mysterious silence

A black Caribbean Surrealist rebel obliquely remembered

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Harvest review - blood, barley and adaptation

An incandescent novel struggles to light up the screen

Friendship review - toxic buddy alert

Dark comedy stars Tim Robinson as a social misfit with cringe benefits

Friendship review - toxic buddy alert

Dark comedy stars Tim Robinson as a social misfit with cringe benefits

S/HE IS STILL HER/E - The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary review - a shapeshifting open window onto a counter-cultural radical

Intimate portrait of the Throbbing Gristle & Psychic TV antagonist

S/HE IS STILL HER/E - The Official Genesis P-Orridge Documentary review - a shapeshifting open window onto a counter-cultural radical

Intimate portrait of the Throbbing Gristle & Psychic TV antagonist

Blu-ray: Heart of Stone

Deliciously dark fairy tale from post-war Eastern Europe

Blu-ray: Heart of Stone

Deliciously dark fairy tale from post-war Eastern Europe

Comments

...