If you liked the Coen Brothers' Inside Llewyn Davis, with its Dave Van Ronk-esque hero in Greenwich Village in 1961, you'll enjoy the new exhibition Folk City: New York and the Folk Music Revival, a celebration of NYC as the centre of folk music from its beginnings in the Thirties and Forties to its heyday in the Fifties and Sixties. It's at the Museum of the City of New York, far uptown at 103rd Street in east Harlem, a block or two from Duffy's Hill, the steepest in New York and the scene of many cable-car accidents in the 19th century. The kind of thing Peter, Paul and Mary might have written a song about.

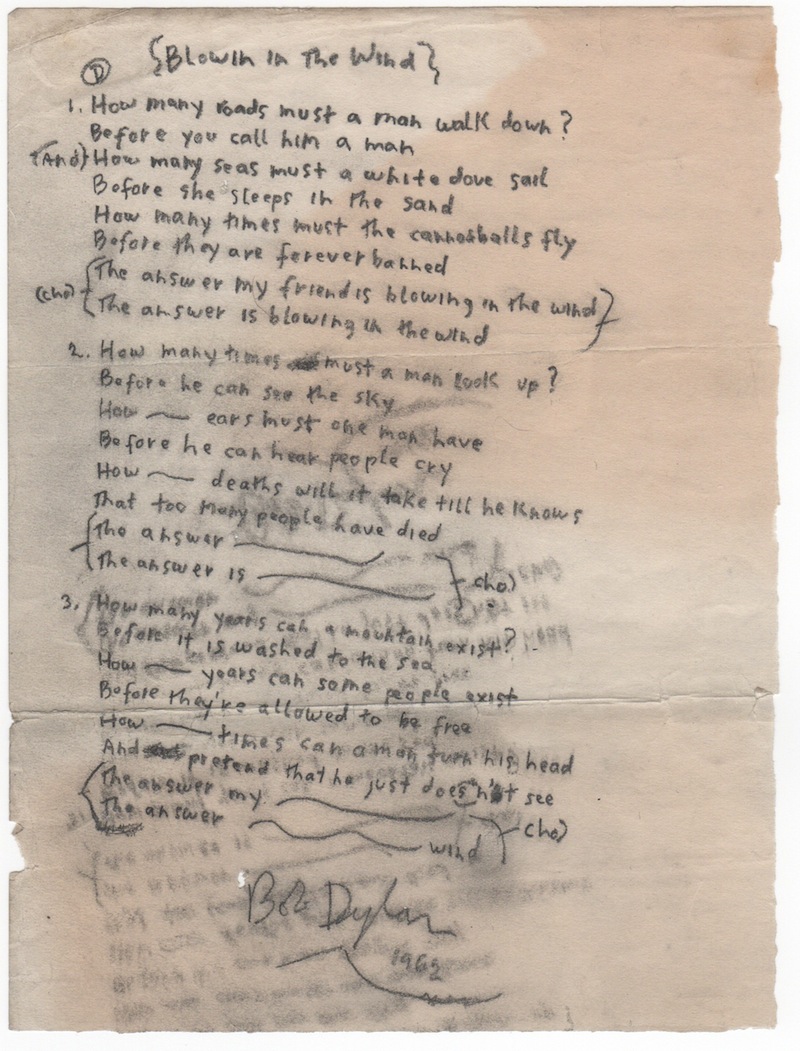

One of their albums features in the Folk City show – the first one, released in 1962, with "Lemon Tree" and "Where Have All the Flowers Gone" on it. ("Probably you're either reading this instead of listening, or else reading and trying to listen at the same time. Either way, it's a mistake. The truth is on the record. It deserves your exclusive attention. No dancing, please," admonish the liner notes). It’s on the wall along with Joan Baez Volume 2, not far from a display case containing, thrillingly, Bob Dylan’s handwritten lyrics to "Masters of War", "Maggie’s Farm", "Mr Tambourine Man" and "Blowin’ in the Wind" (pictured below, private collection).

Also on the wall in this Sixties section are less familiar albums: one by the bluegrass-steeped Greenbriar Boys, another by Fred Neil (he wrote "Everybody’s Talkin’"). And on another wall in an earlier section, there’s Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl Ballads, with a beautiful, misty cover, and one by Aunt Molly Jackson, whose husband was killed in a mining accident. She was jailed for her unionising activities and became a protest singer in the Twenties, moving from Kentucky to New York: "I am a union woman/Just as brave as I can be/I do not like the bosses/And the bosses don't like me." You can hear it at one of the show’s listening stations.

The show is a tantalizing mix of the well-known and unearthed treasures. Here’s Lead Belly’s guitar, Phil Ochs’s felt cap, photos of venues like Gerde’s Folk City, Cafe Wha?, the Bitter End, the Gaslight: the world of Dylan and Van Ronk, of MacDougal and Bleecker Streets. Llewyn Davis territory, in fact. But who remembers the mimeographed Gardyloo (it only lasted for six issues, edited by the intriguing-sounding Lee Hoffman, who also wrote science fiction and Western novels), or Sing Out magazine, whose first issue in 1950 had the "Hammer Song" on the cover? Or even the Almanac Singers, headed by Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, and their 1941 album Songs for John Doe? This anti-war record – one of the songs told Roosevelt off for his military stance – was swiftly pulled one month later when the Germans invaded Russia and the Red Army prepared for battle. The Almanacs’ pacifism was suddenly outdated, and when America entered the war their popularity plummeted. They lived together, all six of them, in Greenwich Village and held hootenannies to raise money for the rent. Llewyn Davis again.

The show is a tantalizing mix of the well-known and unearthed treasures. Here’s Lead Belly’s guitar, Phil Ochs’s felt cap, photos of venues like Gerde’s Folk City, Cafe Wha?, the Bitter End, the Gaslight: the world of Dylan and Van Ronk, of MacDougal and Bleecker Streets. Llewyn Davis territory, in fact. But who remembers the mimeographed Gardyloo (it only lasted for six issues, edited by the intriguing-sounding Lee Hoffman, who also wrote science fiction and Western novels), or Sing Out magazine, whose first issue in 1950 had the "Hammer Song" on the cover? Or even the Almanac Singers, headed by Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, and their 1941 album Songs for John Doe? This anti-war record – one of the songs told Roosevelt off for his military stance – was swiftly pulled one month later when the Germans invaded Russia and the Red Army prepared for battle. The Almanacs’ pacifism was suddenly outdated, and when America entered the war their popularity plummeted. They lived together, all six of them, in Greenwich Village and held hootenannies to raise money for the rent. Llewyn Davis again.

After the war Seeger and Lee Hays, another of the Almanacs, went on to form the Weavers, a quartet. Seeger was keen to reach a wider audience and become more commercial, but the others weren’t so sure – until the American Labor Party said they wanted to book the posh-voiced English tenor Richard Dyer-Bennet (who liked to be called a minstrel) for a benefit concert because he, rather than Seeger, knew how to pull in the crowds. The Weavers, not to be outdone, changed their tactic of only playing political rallies. They began getting nightclub bookings, made their breakthrough at the Village Vanguard nightclub and got signed to Decca. In 1950 they recorded an Israeli soldiers’ song, "Tzena, Tzena", and Lead Belly’s "Goodnight, Irene" (with sanitised lyrics: no mention of morphine, and "I’ll see you in my dreams" rather than "I’ll get you in my dreams"). Both rocketed up the charts. Frank Sinatra recorded "Goodnight, Irene" later, as did several others. "In the summer of 1950, no American could escape that song," said Seeger.

Then came McCarthyism. Folk City reminds you just how evil and career-destroying blacklisting was. The actor, civil rights activist and musician Josh White (huge hit: "One Meatball"), who was one of Roosevelt’s favourites, was at the peak of his career in 1950 before he was labeled a communist sympathiser (pictured left, White testifying at the HUAC in 1950 with his wife beside him; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). His reputation didn’t fully recover until Kennedy invited him to appear on a CBS special, Dinner with the President, in 1963. White came to New York from the Jim Crow South in 1931, part of a wave of musicians discovered by New York record companies who made field trips down South in the Twenties and Thirties, when African-American recordings were known as "race records" (rural white music was "hillbilly" or just "old time music"). This was the era when New York started to dominate the radio and recording industry – it had always been ahead in sheet-music publishing – and what helped turn it, with its mix of club owners, agents, festival organisers and political activists, as well as musicians and immigrants, into folk city.

Then came McCarthyism. Folk City reminds you just how evil and career-destroying blacklisting was. The actor, civil rights activist and musician Josh White (huge hit: "One Meatball"), who was one of Roosevelt’s favourites, was at the peak of his career in 1950 before he was labeled a communist sympathiser (pictured left, White testifying at the HUAC in 1950 with his wife beside him; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division). His reputation didn’t fully recover until Kennedy invited him to appear on a CBS special, Dinner with the President, in 1963. White came to New York from the Jim Crow South in 1931, part of a wave of musicians discovered by New York record companies who made field trips down South in the Twenties and Thirties, when African-American recordings were known as "race records" (rural white music was "hillbilly" or just "old time music"). This was the era when New York started to dominate the radio and recording industry – it had always been ahead in sheet-music publishing – and what helped turn it, with its mix of club owners, agents, festival organisers and political activists, as well as musicians and immigrants, into folk city.

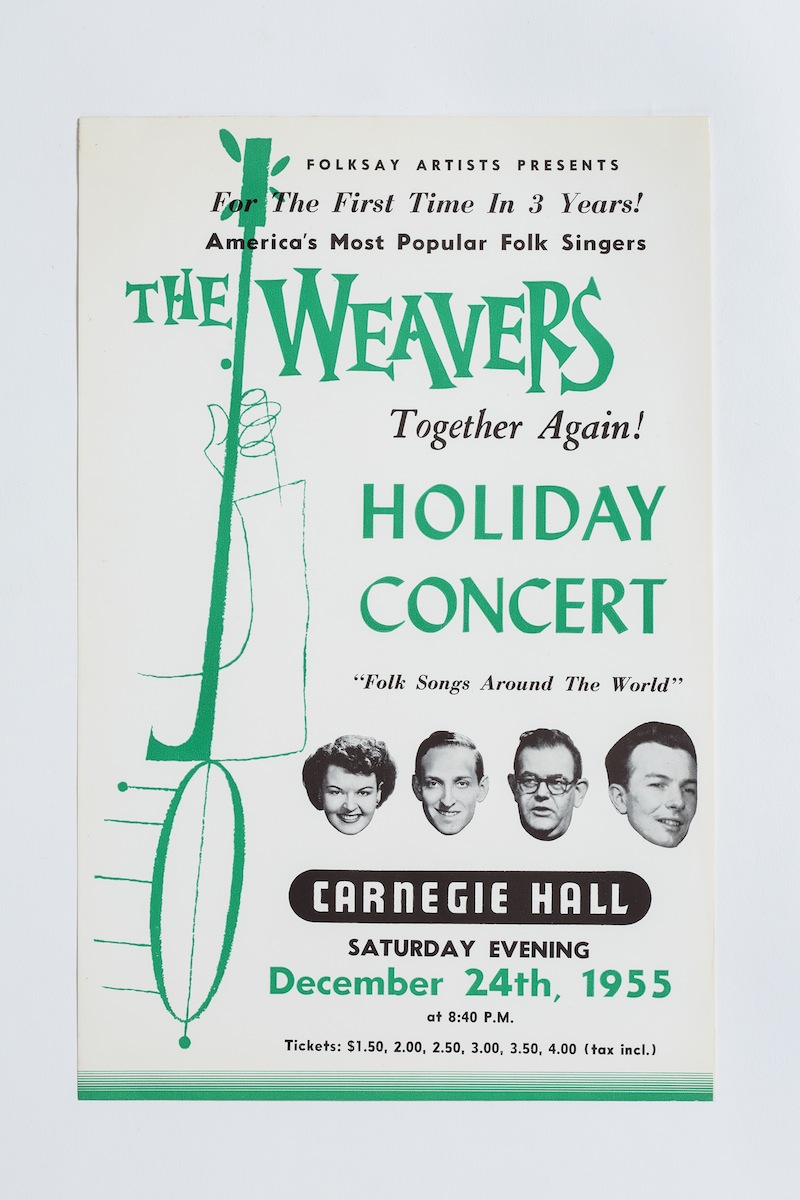

The FBI also monitored the left-wing Weavers, and the anti-communist magazine Counterattack listed Seeger as subversive. Concerts were cancelled, Decca terminated their contract and the Weavers disbanded in 1952. They came together again in a sold-out show at Carnegie Hall on Christmas Eve in 1955 (programme pictured right, Harold Leventhal Collection, photographed by John Halpern). But it wasn’t over: there’s a video of Seeger rehearsing his speech on his way to being sentenced for contempt for refusing to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1961. "A good song can only do good, and I am proud of the songs I have sung," he says.

The FBI also monitored the left-wing Weavers, and the anti-communist magazine Counterattack listed Seeger as subversive. Concerts were cancelled, Decca terminated their contract and the Weavers disbanded in 1952. They came together again in a sold-out show at Carnegie Hall on Christmas Eve in 1955 (programme pictured right, Harold Leventhal Collection, photographed by John Halpern). But it wasn’t over: there’s a video of Seeger rehearsing his speech on his way to being sentenced for contempt for refusing to name names before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1961. "A good song can only do good, and I am proud of the songs I have sung," he says.

If you want more depth and detail, you can get it in Stephen Petrus and Ronald D Cohen's accompanying book, Folk City, with a foreword by Peter Yarrow. I got the subway downtown to Washington Square Park and thought of those Sundays in the Sixties (great documentary about it at the show) when folk singers gathered there until the authorities clamped down. The mayor tried to ban 'minstrelsy', but after weeks of protest marches and arrests, he gave in to the Right to Sing committee. Six hundred folkies marched into the park and sang "This Park is Your Park". Those were the days.

Add comment