I'm at the New Theatre in Oxford. Elvis Costello is playing through the final stages of his 2022 UK tour. The venue is full of memories: I saw The Kinks and Tom Jones here in the 1960s and then The Who in the early 70s. On my left, there’s Paul Conroy who first introduced me to Elvis in 1977 – when he was involved in launching his career at Stiff Records – and on my right, Tom Webber, a super-talented 22 year-old singer from Didcot, Paul’s latest passion, and according to many veterans who have heard him, a potential new star, for whom Paul has come out of retirement to manage, along with his wife Katie.

I can well remember Paul calling me one day, over 40 years ago when he was at Stiff, his voice full of bubbly enthusiasm. He was sending me a single by a new artist that the maverick indie label had just signed. He was called – "wait for this", he said – “Elvis Costello!”. I guessed this might be one more of Stiff’s gimmicks, savvy marketing with an eye and ear to the past as well as to the future. The single duly came in the post. Paul was a joker: I'd met him a couple of years before when I trailed him and the Kursaal Flyers, a wannabe band from Southend, all around England in a white Ford Transit.

There was much in the way of backstage shenanigans, boredom in motel rooms, post-gig blues and wide-eyed groupies. I'd chosen the Kursaals, among other bands on the make, as they had weirdo charisma in buckets, musical talent, a great sense of humour and that ironic yet devoted sense of rock history that characterised so much power-pop and pub rock at the time. Paul Conroy, with a Harpo Marx Afro, was as much of a character in the film as the band. The film grew into So You Wanna Be a Rock’n’Roll Star (1975), one of the first vérité rock-docs, much inspired by DA Pennebaker’s Dylan classic Don’t Look Back (1967). My film created something of a cult. It definitely inspired the Comic Strip’s Bad News Tour (1983), and supposedly after that Rob Reiner’s Spinal Tap (1984)

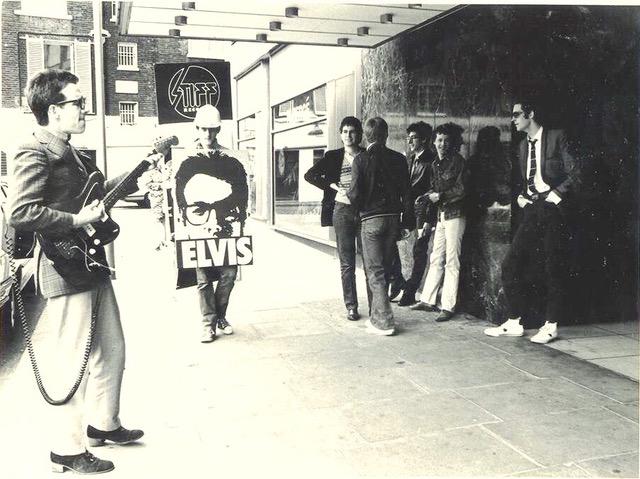

Paul's antics at Stiff – along with Jake Rivera and Dave Robinson (pictured above, Paul Conroy, pictured above at left of group, with Elvis and the Attractions, 1977) – were no surprise to me. They were music fanatics, but also delighted in every marketing trick you could think of, long before Tik-Tok and the machinations of social media. The Elvis Costello single (his very first) was called “Less Than Zero”. The moment I'd put it in on the turntable, I was blown away.

This was something original and new, but shot through with an evident passion for popular music and its rich history. There was irony, and yet a sense of intimacy and vulnerability. It was pop, but it was also fiercely intelligent, all those qualities that we have come to recognise in Costello. Throughout his career, he's constantly and courageously re-invented himself, drawing on a rich musical backstory that reaches into jazz, the Great American Songbook, soul, British '60s pop and the blues.

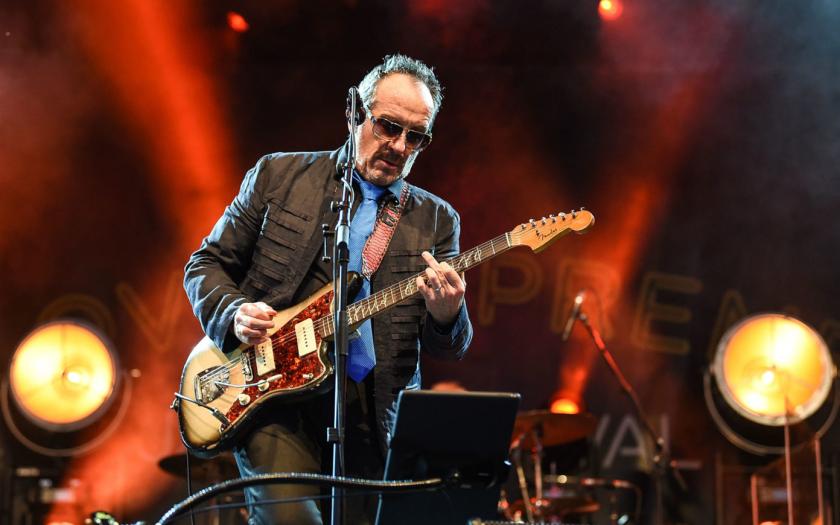

I devoted the whole of my regular rock column in the New Statesman to “Less Than Zero”. This guy, with the edgy and vulnerable voice and clever-but-catchy lyrics, was definitely going to be a star, I wrote without hesitation. I am not sure if Martin Amis, my editor at the Statesman, quite believed my burst of hype, but he acquiesced a few weeks later to a review of Elvis and the Attractions at the Top Rank in Plymouth. Once again, I was blown away: live, the geeky punk version of Buddy Holly was electrifying, and his band were equally breath-taking. Two of them, Steve Nieve on keyboards, and Pete Thomas on drums – among the very best in the business – are still with him today, and as remarkable on stage in Oxford as ever.

Elvis opened the Oxford concert with characteristically self-deprecating stories about his home town and Rusty, his first recording duo with Allan Mayes. Among the songs the audience knew, from his 40 year-plus career, he threw in more recent ones, including "Hetty O'Hara Confidential", an irresistibly rhythmical and jazzy close-to-rap comment on the gossip column industry: toe-tappingly engaging, and dizzy with Elvis's incomparable way with words. His vocals were electronically treated so that it sounded as if his distorted voice came from deep in the vaults, or from an old wireless, of the kind that Bob Dylan might have listened to in 1940s Duluth, Minnesota.

Elvis Costello is a man who has always drawn on the past, and he continues to do so. It was Paul Conroy again who helped me reach out to Elvis a few years ago when I decided to make a feature-doc about his life and work. His record company graciously flew me out to Vancouver for breakfast with the man. I was expecting half an hour or a little more – he was a superstar by now, after all – but, after recalling the interview I’d recorded with him in 1978 for The Observer, when he’d fixed my malfunctioning cassette recorder with great kindness and consideration, we launched into a typical muso’s conversation, and excitedly plunged deep into our shared passions.

An hour in, his management team disappeared, and we carried on, as if inebriated by our enthusiasms, for three solid hours. We talked about the qualities that distinguished the jazz drummer Roy Haynes from Max Roach, Kenny Clarke and Art Blakey. We discussed the various session guitarists who shone at Memphis and Muscle Shoals in the '60s. We talked about Beethoven string quartets and the pianist Alfred Brendel’s interpretations of Haydn and Mozart. We discussed the operas we most liked. We bonded. I had wondered what I should send him before we met as an example of my work. And I had rightly guessed that the film I had made with Robert Wyatt would appeal to him – it was Robert’s touching version of Elvis’s savage and poetic song “Shipbuilding” which put it on the map. My feature documentary Mystery Dance eventually came out in 2013.

When Paul rang me a few months ago, much as he had done all those years ago about Elvis’s first single, raving – albeit with the caution of a senior – about Tom Webber (pictured left with Conroy) a barista at Starbucks in Didcot, telling me the lad had loads of talent – a voice modelled on Sam Cooke, but with his own touch – of course I took note. In the years since Stiff, Paul had risen through the ranks of the record industry, run various record labels, and dealt with some of the greatest musicians of our time. He's perhaps best known for taking a punt, when the Spice Girls – at that point hitless – were looking for a label to sign with. Paul hadn't hesitated, and as he says himself, “the rest is history”. Paul has a good nose.

When Paul rang me a few months ago, much as he had done all those years ago about Elvis’s first single, raving – albeit with the caution of a senior – about Tom Webber (pictured left with Conroy) a barista at Starbucks in Didcot, telling me the lad had loads of talent – a voice modelled on Sam Cooke, but with his own touch – of course I took note. In the years since Stiff, Paul had risen through the ranks of the record industry, run various record labels, and dealt with some of the greatest musicians of our time. He's perhaps best known for taking a punt, when the Spice Girls – at that point hitless – were looking for a label to sign with. Paul hadn't hesitated, and as he says himself, “the rest is history”. Paul has a good nose.

Taking Tom Webber to see Elvis Costello is part of the young man’s training. Thanks to Paul’s extensive network of friends, Tom was taken on as support act for Nick Lowe’s recent UK tour. He couldn't have had a better mentor. The gigs have started coming, just in the last few months. This summer he's doing a string of festivals.

As I write this, he's doing sets on three different sages at the Isle of Wight. I've been shooting material on spec, watching as Paul and Katie learn the new ways of launching an artist, and chronicling from the earliest stages what could well be the making of a star. Tom is very much his own man – he's not another Elvis Costello. But he shares with him a taste for the music of his parents and grandparents.

Tom's granddad was into Howlin' Wolf, his father into Sixties soul. Tom is, in the best sense, a little retro, without being in the slightest bit nostalgic. He's well soaked in the past, but he makes it new. In a few days’ time, he is really coming out: only six or so months after starting to perform, he's playing the Acoustic Stage at Glastonbury.

- Tom Webber plays the Acoustic Stage at Glastonbury Festival, Saturday 25 June at 12 noon

- More New Music on theartsdesk

Add comment