The Shepherd – original title El pastor – is a Spanish film which carried all before it at the Raindance Festival. It’s a very Raindance kind of movie. Shot on a low budget with a small cast, a single handheld camera shaking like a leaf, it sticks up for the little guy against a big bad corporate world.

Japanese director Hirokazu Kore-eda is a master of family drama, carrying on the traditions of his illustrious predecessors Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse. But these are not films of raised voices or open conflict, rather highly nuanced studies of the emotional dynamics between parents and children – differences across the generations – or partners whose relationships have cooled. There’s always a gently melancholic tinge, and Kore-eda has a particular gift for working with his child actors, movingly presenting their point of view on the issues that divide the adults who surround them.

In addition, Kore-eda has assembled almost a company of actors with whom he has regularly worked from film to film, creating the effect almost of a family in itself. It makes for a rare intimacy. In After the Storm his mother and son protagonists are played by Kirin Kiki and Hiroshi Abe, who played similar roles in his 2008 masterpiece Still Walking. Abe plays Ryota, something of a prodigal who has come back into the life of his mother, Yoshiko, after the death of his father. Well-aware of her son’s shortcomings – which seem to repeat many of those she put up with from her late husband – she accepts him without judgment.

Abe’s hangdog face is an expressive joy in itself

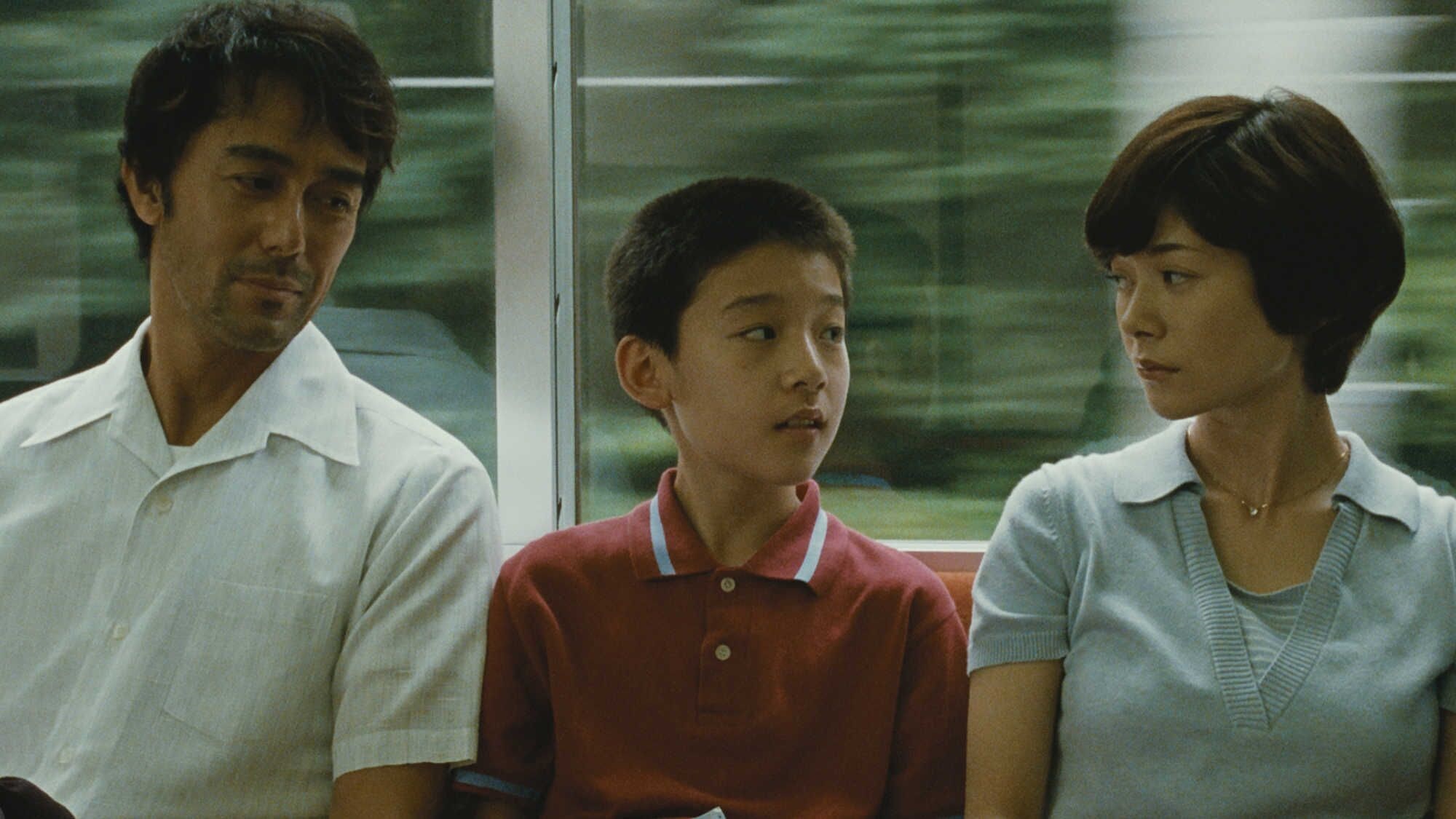

The same can’t be said for his estranged wife, Kyoko (Yoko Maki). Their meetings, arranged formally for the father to see his young son Shingo (Taiyo Yoshizawa, another child role masterfully drawn out by the director), are coloured every time by his failure to produce the maintenance payments he is supposed to. However, the closeness between father and son is powerfully felt, and reciprocal, even if Ryota struggles to give him the kind of gifts being offered by Kyoko’s new partner (and, perhaps, husband-to-be).

The context of divorce is one Kore-eda explored in his 2011 I Wish, while the nature of family loyalties were at the centre of his more complicated Like Father, Like Son, from 2013. But there’s something of a new element in After the Storm, a degree of rather macabre comedy less familiar from his work. Some 15 years earlier Ryota had published an acclaimed first novel, but his literary career has clearly stalled. For some time he’s been working for a detective agency, ostensibly claiming it as research for a new book, but it’s clear that he’s staying there because it’s the only source of the cash he needs to keep a roof over his head.

As well as the more mundane tasks of detective work like lost pets, the agency seems to specialise in divorce work, following unfaithful partners for evidence that they are cheating on their marriages, and the like. However, Ryota has made a personal speciality of exploiting such cases for his own ends – he’s an adept at blackmail, or selling incriminating evidence to the guilty party, even shaking down a kid for money to hush up a liaison. Abetted by a fresh-faced colleague, he’s unscrupulous in almost every respect, yet the repercussions of his actions never seem to catch up on him (in a different movie genre, he’d be up making some nasty enemies). He’s doing this, we discover, to feed his longterm gambling habit.

As well as the more mundane tasks of detective work like lost pets, the agency seems to specialise in divorce work, following unfaithful partners for evidence that they are cheating on their marriages, and the like. However, Ryota has made a personal speciality of exploiting such cases for his own ends – he’s an adept at blackmail, or selling incriminating evidence to the guilty party, even shaking down a kid for money to hush up a liaison. Abetted by a fresh-faced colleague, he’s unscrupulous in almost every respect, yet the repercussions of his actions never seem to catch up on him (in a different movie genre, he’d be up making some nasty enemies). He’s doing this, we discover, to feed his longterm gambling habit.

He has even been sleuthing on Kyoko, as well as drawing facts about her new life out of Shingo. All of this is background context for a day in which the paths of the trio cross, first as father and son spend time together in the city, then when the three of them end up in Yoshiko’s humble flat. We’ve been aware of typhoon warnings throughout the film, and when one finally breaks, they are forced to spend the night there, giving rise to a series of conversations that reassess the past, the hopes with which each character had started, and where they have ended up. The storm may be raging outside, but its still centre for Kore-eda is playing out with a potent intimacy within these cramped apartment walls. (Pictured below: Hiroshi Abe, Taiyo Yoshizawa, Yoko Maki)

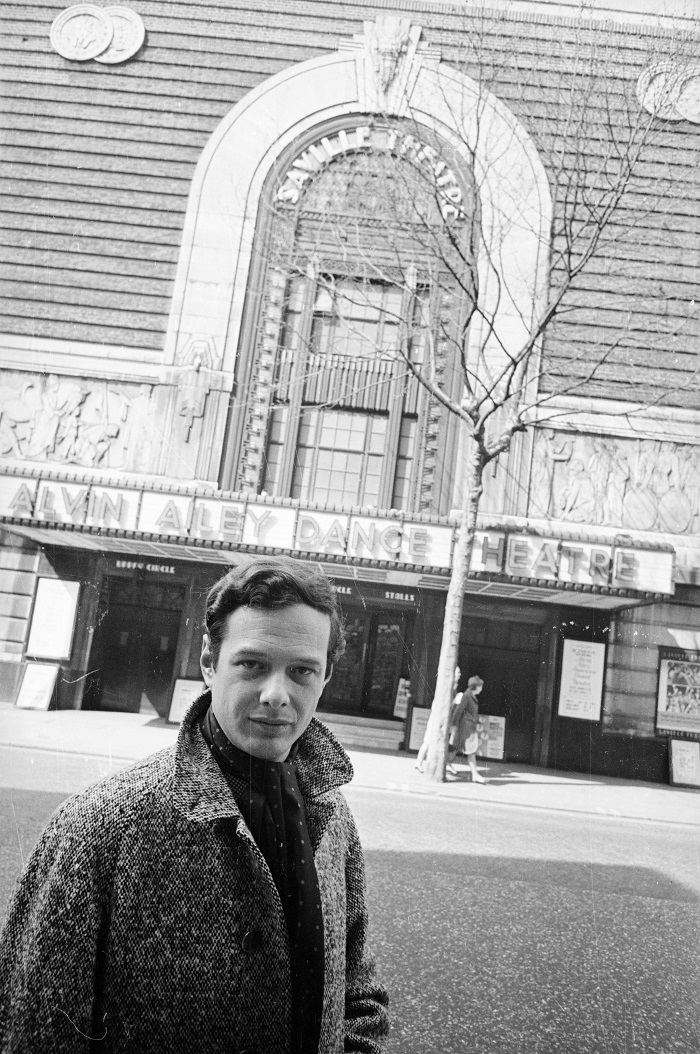

It gives rise to a moving denouement, one which even offers hints, however tentative, of hope for the future. Yoshiko may be aware of her encroaching end (“new friends at my age only mean more funerals”), yet hasn’t lost interest in life, even joining a classical music group to discuss Beethoven (she has a soft spot for the teacher, too). Abe’s hangdog face (pictured, top) is an expressive joy in itself, and we somehow can’t help feeling for this undoubted scamp who nevertheless doesn’t seem to mean any harm (“How did my life get so screwed up?” he asks himself). Yoshizawa as the sensitive Shingo beautifully captures the complicated nuances of the child’s love for his unreliable dad, which makes for a loyalty that endures regardless of what he gets up to.

It gives rise to a moving denouement, one which even offers hints, however tentative, of hope for the future. Yoshiko may be aware of her encroaching end (“new friends at my age only mean more funerals”), yet hasn’t lost interest in life, even joining a classical music group to discuss Beethoven (she has a soft spot for the teacher, too). Abe’s hangdog face (pictured, top) is an expressive joy in itself, and we somehow can’t help feeling for this undoubted scamp who nevertheless doesn’t seem to mean any harm (“How did my life get so screwed up?” he asks himself). Yoshizawa as the sensitive Shingo beautifully captures the complicated nuances of the child’s love for his unreliable dad, which makes for a loyalty that endures regardless of what he gets up to.

Played in a plangent, minor key, After the Storm is rich in whimsy, with Hanaregumi’s score drawing plentifully on whistling, to give the sense of an everyday amble through life’s unpredictabilities. It’s set in a dormitory suburb of Tokyo, Kiyose, where Kore-eda spent part of his youth, a slightly down-on-its-luck neighbourhood that life seems to have in some sense passed by, just as it has the director’s protagonists. It’s a perfect location for a film that ruefully captures a sense of life's tribulations, as well as its occasional small joys.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for After the Storm

Oh dear, writing this review is a bit like being mean to a small cuddly animal. Dough has such very good intentions – characters separated by race, religion and age can find common ground in a bakery – it’s a shame that it doesn’t rise into a tasty loaf but instead remains just a bit wholemeal and stolid.

The excellent Jonathan Pryce plays Nat Dayan, an orthodox Jewish widower whose sole reason to get up every morning at four is to work in his beloved shop. He inherited it from his father and still bakes traditional bagels, pastries and challah bread. But the neighbourhood’s changing, customers are dwindling and his assistant has quit to work in the rival supermarket next door. Nat’s son has gone up in the world and is a lawyer; he isn’t interested in taking over the business and wants his dad to retire. Joanne Silberman (Pauline Collins) plays a frisky widow who owns the freehold, and she’s keen to sell the building to an evil developer (Phil Davis, practically twirling a villain’s moustache). Nat is stubbornly holding on to tradition, but needs help.

Meanwhile in a parallel narrative (it’s literally cross-cut) we meet Ayyash (Jerome Holder, pictured below with Pauline Collins and Jonathan Pryce), a young refugee from Darfur. He’s trying to get a job with the local drug baron (played by Ian Hart, sporting a shaved head); he’ll take Ayyash on as a dealer if he’s got a cover job. Working at the bakery as Nat’s apprentice provides Ayyash with the perfect front. Soon he is selling bags of weed alongside the muffins to those customers in the know and business turns around for all concerned. Nat doesn’t know about the sideline sales, and becomes fond of the young man, impressed by his baking skills and touched by his piety – Ayyash doesn’t get high on his own supply and is a devout Muslim. In another cross-cut sequence we see both men performing their particular ritual prayers in separate areas of the bakery. It’s all very well-meaning, hands-across-the-divide stuff with plenty of gags about Jewish and Muslim preconceptions about each other, but it pulls its punches. It would have been braver to have had Ayyash come from the Middle East rather than Africa.

Nat doesn’t know about the sideline sales, and becomes fond of the young man, impressed by his baking skills and touched by his piety – Ayyash doesn’t get high on his own supply and is a devout Muslim. In another cross-cut sequence we see both men performing their particular ritual prayers in separate areas of the bakery. It’s all very well-meaning, hands-across-the-divide stuff with plenty of gags about Jewish and Muslim preconceptions about each other, but it pulls its punches. It would have been braver to have had Ayyash come from the Middle East rather than Africa.

Dough aims for the comedy-caper genre, with gags around cultural and generational misunderstandings and shenanigans with the police and local criminals, but it relies on bland stereotypes and despite the best efforts of its actors, they cannot rise above a clichéd and implausible script by first time writers Jonathan Benson and Jez Freedman. After Ayyash accidentally adds a bag of weed to the challah dough, no-one notices the resulting loaves taste and smell different, but all just enjoy the giggles and crave more – no matter how orthodox they are. Soon he’s dumping bags of grass into brownies and other sweet treats and there are queues around the block and smiles all round. Sadly, a cursory browse of the many online recipes for cooking with marijuana would have disabused the writers of the efficacy of this method (there are some delightful how-to videos out there).

It’s not just problems with the script; there’s a flatness to the lighting of the interior scenes which make them look like cheap TV, and an absence of a sense of place with few exterior scenes. Dough is a Hungarian-British co-production and, judging by the credits, a lot of it was shot in a studio in Budapest with a few location scenes in the UK, and it shows. This is veteran TV drama and documentary director John Goldschmidt's first film in many years (his credits include helming Jack Rosenthal’s wonderful Spend Spend Spend in 1977) and it’s waited two years to get a cinema release in the UK after doing reasonable business in the USA. It would be lovely to acclaim it as a lost gem, but unfortunately that’s not the case.

Overleaf: watch the official trailer for Dough

After dipping a toe in the new-look DC Comics universe to brighten the otherwise leaden Batman v Superman, now Gal Gadot’s Wonder Woman gets a chance to shine in her own Hollywood movie. Gadot makes a pretty fine job of it too, bringing a bit of soul and empathy to the proceedings, but sometimes it’s more despite than because of the production surrounding her.

A man is caught up in a storm at sea; giant waves like Hokusai crests throw him onto a deserted tropical island. Over the next 80 minutes, his struggle to survive occupies the screen. Curious crabs provide a little company, but not enough to stop him trying to make a raft only to have his attempts at escape thwarted. While he is eventually blessed with some human companionship, there is no dialogue throughout the film, just music and sound effects.The Red Turtle features many beautiful sequences set in bamboo forests and thrilling underwater scenes, but it's a slow watch and at a couple of points, quite upsetting for a tender-hearted child. It is tricky to see this becoming a family favourite. This is animation for the art house, not the theme park.

Over the three decades it has been making films, Studio Ghibli has created its own fantastic universe, populated by magical creatures and quirky humans. Although its films are usually set in Japan (Totoro, Spirited Away, Grave of the Fireflies), sometimes its heroes have strayed into unspecified mittel-European towns (Kiki's Home Delivery, Howl's Moving Castle) and purely fantastical landscapes (Tales from Earthsea).

Over the three decades it has been making films, Studio Ghibli has created its own fantastic universe, populated by magical creatures and quirky humans. Although its films are usually set in Japan (Totoro, Spirited Away, Grave of the Fireflies), sometimes its heroes have strayed into unspecified mittel-European towns (Kiki's Home Delivery, Howl's Moving Castle) and purely fantastical landscapes (Tales from Earthsea).

But this is the first time the studio has co-produced a film with European backers and it has a very different feel. The Red Turtle is directed by Michaël Dudok de Wit, a Dutch animator who made the short Father and Daughter, which won an Oscar in 2001.

That short was the tale of a young woman growing away from her father, replete with dream sequences, and there are echoes of it here in The Red Turtle with its narrative of family bonds stretching out over time. Perhaps if viewers come to the film not craving the humour, pathos and quirky inventiveness of classic Studio Ghibli, they won't be disappointed. As it is, while admiring the atmospheric animation I was left a little underwhelmed by the ponderous narrative.

Overleaf: watch the official trailer for The Red Turtle

It takes real skill to make a film about a desperate Syrian refugee and a dour middle-aged Finn reinventing himself and turn it into the warmest, most life-enhancing film I’ve seen this year. But Aki Kaurismäki has form, he’s been making movies which defy genres – are they absurdist or social realist, tragic or comic? – for 30 years now. His films do well at festivals – The Other Side of Hope won Berlinale's Silver Bear for best director this year – and regularly find their way onto the indie circuit but they never make it in the multiplex: you’ll need to be quick to catch this one on a big screen, which is where it belongs.

There’s some thematic overlap here with Kaurismäki’s most recent film, 2011’s Le Havre, which also featured a refugee finding an unexpected ally in France, but the director is back on home turf here and it's a shade darker - there are encounters with Nordic neo-Nazis and chilly officialdom. Khaled (Sherwan Kaji) has been travelling for months since his home in Aleppo was bombed while his family were having lunch; the only other survivor was his sister, Miriam and he’s lost her in some hellish border camp.

Finding Miriam is his sole reason to live, and he’s been criss-crossing borders searching for her before ending up by mistake on a freighter bound for Finland. Khaled's journey is intercut with the story of Waldemar Wikström (Sakari Kuosmanen) who is also on the run, but from the boredom of marriage and work. There's a lovely deadpan scene where his wife sits in the kitchen, her hair in rollers mimicked visually by the giant cactus on the table, and dumps his discarded wedding ring among the cigarette butts.

Wikström also jettisons his boring job selling clothes to small outfitters around the country. He flogs off his stock of cellophane-wrapped shirts for a derisory sum and is left with his big old car and a handful of cash. Instead of heading for sunnier climes, he buys a shabby drinkers’ dive, the Golden Pint, where fishballs are always dish of the day. The three surly staff haven’t had their wages paid in months and regard the new owner with suspicion. It's more than an hour into the film before Khaled and Wikström meet, and then it isn't exactly cute – a fight by the restaurants' bins – but a friendship develops.

Wikström also jettisons his boring job selling clothes to small outfitters around the country. He flogs off his stock of cellophane-wrapped shirts for a derisory sum and is left with his big old car and a handful of cash. Instead of heading for sunnier climes, he buys a shabby drinkers’ dive, the Golden Pint, where fishballs are always dish of the day. The three surly staff haven’t had their wages paid in months and regard the new owner with suspicion. It's more than an hour into the film before Khaled and Wikström meet, and then it isn't exactly cute – a fight by the restaurants' bins – but a friendship develops.

Much of the comedy lies in the attempt to reinvent the Golden Pint and bring in more customers with a new menu. Transforming into a sushi restaurant (pictured below) backfires horribly when the cook swiftly runs out of fresh fish and resorts to dolloping lumpy clods of wasabi on rinsed-off pickled herring. Where another director would give you the Japanese diners’ disgusted reaction, Kaurismäki just cuts to them walking politely out of the restaurant at the end of the evening, nodding to the staff dressed in their absurd kimonos. Back to the fishballs.

There are many familiar pleasures from the director whose biggest hit was Leningrad Cowboys Go America back in 1989. The Other Side of Hope generously showcases the indigenous bar band circuit of Finland. Who knew that there were still so many hairy Finnish musicians who sound like Dire Straits and sing fabulously miserable songs? And for those mourning Laika, the adorable dog in Le Havre, there is a new dog to provide some winsome comedy at the diner when the health and safety inspectors come to call.

There are many familiar pleasures from the director whose biggest hit was Leningrad Cowboys Go America back in 1989. The Other Side of Hope generously showcases the indigenous bar band circuit of Finland. Who knew that there were still so many hairy Finnish musicians who sound like Dire Straits and sing fabulously miserable songs? And for those mourning Laika, the adorable dog in Le Havre, there is a new dog to provide some winsome comedy at the diner when the health and safety inspectors come to call.

The gently lugubrious humour is matched by superb camerawork (the film is shot on 35mm film by Kaurismäki's longterm cinematographer Timo Salminen). The limited palette and subdued lighting renders every location a glaucous underworld. But this movie isn’t all style and poker-faced comic asides, there’s a really profound humanism in the way the refugees’ stories are told, and a compassion which is all the more impressive for its total lack of sentimentality. Kaurismäki has said that this is his final film; it would be a real shame for him to stop now, but at least he’d be going out on a masterpiece.

Overleaf: watch the official trailer for The Other Side of Hope

There are great sportsmen, and on top of those there’s a handful of phenomena. Sachin Tendulkar is one of the latter, a cricketer of seemingly limitless gifts who’s ranked among such deities as Viv Richards and Brian Lara. Or even Don Bradman, who pops up in an archive clip in this weighty biopic saying that this bloke Tendulkar bats like he used to.

We’ve recently seen how Formula One heroes Ayrton Senna, Niki Lauda and James Hunt can become box office gold, in the form of Senna and Rush.

This is the most frustrating film. It’s probably no fault of the makers, but it’s rare to have to assess a documentary for what it doesn’t have. Over nearly two hours of celebrating the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band Beatles period – late 1966 to their record label Apple taking off in 1968 – there is not a note of the group’s music.

Well, alright, in the opening animated credits you detect a phrasal shimmer of George Harrison’s sitar-driven “Within You Without You”, but that’s it. The score, by Andre Barreau and Evan Jolly, is a confection of atmospherics and rhythms that could be the Beatles but absolutely isn’t.

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band is the most famous album of the 20th century. The LP practically defines the last part of it. On paper, it makes real sense to release a half-century anniversary documentary about the trailblazer. But it’s asking a lot of someone aware of the Beatles brand and familiar with, say, a handful of their best-known songs to be amused by or engaged in chitchat about – the here non-heard – “Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite!” or “Lovely Rita” if they don’t know them. Unfortunately, that is a legacy downside of the group’s global reach: Apple Corps, representing the interests of Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and the estates of John Lennon and George Harrison, will – putting it simply – just say no to anyone seeking to broadcast or exploit Beatles originals in the public domain, unless four parts are in total agreement and involved. So it was that, by contrast, Ron Howard last year stole a march on Alan G. Parker, maker of this new film, by having – with the help of producer George Martin’s son Giles and presumably Apple – original live sound in Eight Days A Week, about the touring years, as well as new spoken contributions from McCartney and Starr. Neither appears in It Was Years Fifty Ago Today! Who does?

Unfortunately, that is a legacy downside of the group’s global reach: Apple Corps, representing the interests of Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr and the estates of John Lennon and George Harrison, will – putting it simply – just say no to anyone seeking to broadcast or exploit Beatles originals in the public domain, unless four parts are in total agreement and involved. So it was that, by contrast, Ron Howard last year stole a march on Alan G. Parker, maker of this new film, by having – with the help of producer George Martin’s son Giles and presumably Apple – original live sound in Eight Days A Week, about the touring years, as well as new spoken contributions from McCartney and Starr. Neither appears in It Was Years Fifty Ago Today! Who does?

The four themselves, of course, in black and white, from various clips amassing from 1963 in the form of cheeky and, increasingly in 1966, combative press conferences. Many of these can be found on YouTube. One of the more intensive periods of defence-before-the-press was as they headed for the last-ever tour, of America in August 1966. Lennon had set the fires blazing in the Bible Belt by a casual comparison to Christ and the Beatles being more popular… It was really the turning-point in the band’s relation to their gargantuan public. After horrible experiences in the US (and, just before, in the Philippines) they vanished from view. What emerged in 1967 was a completely refashioned quartet, an utterly different sound world and, from behind closed doors, astonishingly innovative recording techniques.

This is the frame for Parker’s film: historical, cultural, anecdotal. Analysis of the Pepper music is of necessity skimpy, as the film gives us in that respect nothing to listen to. Useful and largely articulate talk comes from well-known Beatles commentators such as biographers Philip Norman and Hunter Davies and journalist Ray Connolly, and from – until now – relative unknowns such as Barbara O’Donnell, who worked for manager Brian Epstein, and Jenny Boyd, sister of Harrison’s first wife Pattie, coming across still as a cut-glass 1960s charmer. Rather sweetly, a groomed, smiling, 75-year-old Pete Best, sacked as drummer in 1962, has some screen-time to praise his three long-lost friends, though this is inessential as of course he had nothing to do with Pepper or, indeed, the recorded legacy.

This is the frame for Parker’s film: historical, cultural, anecdotal. Analysis of the Pepper music is of necessity skimpy, as the film gives us in that respect nothing to listen to. Useful and largely articulate talk comes from well-known Beatles commentators such as biographers Philip Norman and Hunter Davies and journalist Ray Connolly, and from – until now – relative unknowns such as Barbara O’Donnell, who worked for manager Brian Epstein, and Jenny Boyd, sister of Harrison’s first wife Pattie, coming across still as a cut-glass 1960s charmer. Rather sweetly, a groomed, smiling, 75-year-old Pete Best, sacked as drummer in 1962, has some screen-time to praise his three long-lost friends, though this is inessential as of course he had nothing to do with Pepper or, indeed, the recorded legacy.

Most interesting of all is ex-pop manager Simon Napier-Bell, fearsomely intelligent, who reckons he was the last person to “hear” Brian Epstein. Epstein’s death from pills and booze in August 1967 was a complicated affair, as traumatic to the four as the death threats of 1966. He, too, hadn’t had much to do with Pepper and without question was feeling sidelined. In his last days he was, if Napier-Bell remembers right, hoping to get the younger man into bed, but Napier-Bell was in Ireland (and never, anyway, going to do Epstein’s bidding). He had invented an early version of the answerphone. On his return to London he heard a succession of blurred messages from the 32-year-old, left through the evening of his death. What Napier-Bell reveals next, one of the more jolting moments in the film, would amount to a spoiler...

Two significant survivors drastically missing here are Epstein’s lieutenant Peter Brown and McCartney’s girlfriend for most of the Beatles era, Jane Asher. Both are alive and thriving, can claim to have been in the eye of the storm from 1963 and would, as interviewees, have been not just feathers in Parker’s cap but lightning-bolt scoops. Alas, they are as likely to talk as Parker was of getting even two seconds of “A Day in the Life”. But those two saw it all.

We must be content with some rare footage not of Pepper-making – that would be gold-dust – but of events early in the Apple years: glimpses of each Beatle in a world even further removed from the protective luxuries and early-form showbiz high security of the touring years. After Pepper they rocketed into, even for them, entirely untested territory of fame. The main virtue of It Was Fifty Years Ago Today! is to remind us how they shaped not only the late 1960s but, in senses more than musical, the very culture of the 20th century’s last third.

Overleaf: watch the trailer to It Was Fifty Years Ago Today!

Inversion may not be the catchiest of titles, but in the case of Iranian director Behnam Behzadi’s film its associations are multifarious. On the immediate level it refers to the “thermal inversion” that generates the smogs that engulf his location, Tehran, and also direct his story. Meteorologically, the phenomenon happens when a layer of warm air sits over one of cold, preventing it from rising, and trapping pollutants in the atmosphere.

But there’s surely a deeper relevance in this story of family conflict – in particular sibling antagonism – that relates to the position of women in Iranian society, how their assertions of independence can be easily blocked by the society (and not only by the men) that surrounds them. The stand-off in the Earth’s atmosphere compares, at least loosely, with the human oppositions that Behzadi depicts in his film.

It details the struggles to negotiate the variety of complications that life throws up

However, its opening depicts a world in which women are existing rather comfortably on their own terms. Niloofar (Sahar Dolatshahi) lives with her mother Mahin (Shirin Yazdanbakhsh): she is the youngest child, and remains unmarried, while her older brother and sister have their own families. It’s not that she looks after the older woman, who lives a busy and independent life which is curtailed only by her health problems. When the Tehran smog is heavy, Niloofar tries to prevail on her mother to stay at home; the latter insists, almost skittishly, that as long as she has her medicine and oxygen with her, all will be well.

It’s a middle-class environment that allows Niloofar to live an independent life, running the tailoring business that belonged to her late father: she has developed it over more than a decade, and has further plans for expansion. There appear to be no restrictions in her professional world and, unknown to her family, she has renewed contact with a childhood friend who has returned to Tehran from abroad, and their interaction is beginning to look like they are dating. Again, it’s a process in which Niloofar is an equal player.

When the inevitable happens, and Mahin ends up in hospital, all that looks set to change. The doctor’s prognosis is uncompromising: Mahin must leave Tehran, or the consequences will be fatal. There isn’t so much a family conclave, as a decision, without discussion, by the two married siblings that Niloofar will accompany her, leaving her life and work in Tehran behind. “No husband, no children, so I don’t count?” is her retort, as the family encounters become increasingly confrontational (not least when her brother simply shuts her out of her work premises, to pay off his own debts). The older sister sees it as no less of a transaction: in return for going with the mother, Niloofar will receive an allowance. (Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Mosaffa, playing her brother, pictured above)

When the inevitable happens, and Mahin ends up in hospital, all that looks set to change. The doctor’s prognosis is uncompromising: Mahin must leave Tehran, or the consequences will be fatal. There isn’t so much a family conclave, as a decision, without discussion, by the two married siblings that Niloofar will accompany her, leaving her life and work in Tehran behind. “No husband, no children, so I don’t count?” is her retort, as the family encounters become increasingly confrontational (not least when her brother simply shuts her out of her work premises, to pay off his own debts). The older sister sees it as no less of a transaction: in return for going with the mother, Niloofar will receive an allowance. (Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Mosaffa, playing her brother, pictured above)

Yet these loyalties aren’t quite so one-sided. Niloofar’s teenage niece Saba (Setareh Hosseini) implicitly takes the side of her aunt (she can see how her own future might develop). The possibilities of the burgeoning romantic attachment may be tested when certain other dependencies are revealed, but such difficulties can be negotiated (it involves a great deal of to-and-froing on the Tehran mobile network). And, as the matriarch begins to recover she reveals a keener will than anyone had anticipated.

The elements of drama are strong, and give the film’s closely observed scenes – even when a touch of melodrama slips in, Inversion is still very much a work of realism – their power. It premiered at Cannes last year in the “Un Certain Regard” programme, and the quality of the acting impresses profoundly. Dolatshahi has a paradoxical combination of composure and vulnerability, and her face captivates the camera: she’s matched by the utterly natural Hosseini, the youngest presence on the screen, as well as by the scheming siblings, unsympathetic but still somehow understandable. Such a keen definition of character more than compensates for a budget we assume was modest. (Romantic interest: Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Reza Aghakhani, pictured above)

The elements of drama are strong, and give the film’s closely observed scenes – even when a touch of melodrama slips in, Inversion is still very much a work of realism – their power. It premiered at Cannes last year in the “Un Certain Regard” programme, and the quality of the acting impresses profoundly. Dolatshahi has a paradoxical combination of composure and vulnerability, and her face captivates the camera: she’s matched by the utterly natural Hosseini, the youngest presence on the screen, as well as by the scheming siblings, unsympathetic but still somehow understandable. Such a keen definition of character more than compensates for a budget we assume was modest. (Romantic interest: Sahar Dolatshahi with Ali Reza Aghakhani, pictured above)

Inversion doesn’t quite fit into the arthouse strand of Iranian cinema that is best known in the West (and it certainly doesn’t belong to the mainstream that dominates the country’s film industry). Possibly, at home, it falls into what's called the “popular art” genre, and its concerns – detailing the struggles to negotiate the variety of complications that life throws up – are close to those of Asghar Farhadi’s recent The Salesman. Both deal with the consequences of a settled life being disrupted. Though European realism might also be another point of reference, Behzadi’s brisk conclusion consciously leaves any such allegiance behind – in a way that feels more accomplished cinematically than it does thematically.

To say that a film opens up a world to us may seem a double-edged compliment. After all, why should we be surprised to recognise patterns of life in Tehran as somehow familiar – even if we think of Iran as “closed” in some way? Surprisingly, I’m drawn to comparisons with Jon Snow’s broadcasts for Channel 4 this week on the Iranian elections, which conveyed something, however briefly, of what life there, in all its contradictions, may be like. For almost an hour-and-a-half Inversion anchors us in Behzadi’s here-and-now. It is no small achievement.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Inversion