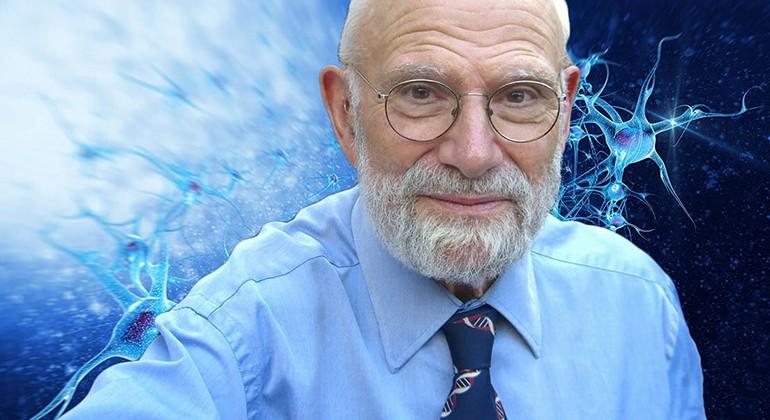

It’s well worth tracking down one of the September 29 special cinema screenings of Ric Burns' lovingly made documentary portrait of the writer and neurologist Oliver Sacks, or seeking it out online. Famous for his vivid, insightful descriptions of people living with disabling conditions (Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, An Anthropologist on Mars), Sacks was born into a brilliant Jewish family of doctors in north-west London in 1933, but after studying medicine at Oxford, spent most of his working life in America.

Burns had the luxury of making the film with full co-operation from Sacks himself, who made his extensive personal archive available to him. The documentary opens in 2015 with an interview filmed in Sacks' office, surrounded by friends and colleagues, as the 82-year-old describes how his cancer has metastasised and outlines his plans for the brief time he has left. Burns has assembled a stellar cast of family and friends, including the late Jonathan Miller (who went to school with Sacks) and remembers him as a brilliant but chaotic young man.

There's a wonderful interview with the great French neurologist Isabelle Rapin, who helped Sacks in his early years in the US and became his mentor when he was beset with personal demons that led him to amphetamine addiction. Scarred by his surgeon mother’s disapproval of his homosexuality (she described it as "an abomination"), Sacks struggled to find romantic love until well into his 70s.

There are valuable insights too from the American surgeon and writer Atul Gawande who describes Sacks in his youth as brilliant but self-destructive and pays tribute to his skill as a writer able to bring complex science to a wide audience. Only occasionally does the documentary drift into hagiography when interviewees such as Paul Theroux and Robert Krulwich fall over themselves to praise Sacks.Burns has ample access to an extraordinary rich archive of film and photographs. We see Sacks in his California heyday as an impressive weightlifter and enthusiastic biker (pictured above, in full Tom of Finland leathers), who would go on marathon long-distance rides to blot out his unhappiness. The filmed recordings from the early '70s of the (temporary) recovery of patients who were victims of the 1920s encephalitis lethargica epidemic are as moving as ever.

The neurologist's book about his patients' "awakening" from a seemingly near comatose state after he gave them the Parkinson's drug L-DOPA, became an acclaimed Yorkshire Television documentary in 1974. Sixteen years later it was turned into a somewhat mawkish Hollywood feature film starring Robin Williams and Robert De Niro.

I filmed an interview with Sacks for the BBC's Late Show when he was brought to the UK to publicise Awakenings by the studio which had made it. It was painful to watch his emotional distress when he was asked about the script-writers' wholesale invention of a redemptive romance between his on-screen character and a kindly nurse. Much of the interview ended up on the cutting-room floor. Off camera he told me that he had ignored the imagined romance completely; all that had mattered to him was that the actors playing the patients with encephalitis portrayed them accurately.

There’s no space in Burns documentary for the criticism that Sacks received from disability activists and academics, particularly geneticist Tom Shakespeare. In 1996 he described Sacks' accounts of his patients as akin to a colonialist patronisingly describing the natives and not allowing them to speak for themselves. Perhaps because Burns was aware of the criticism, he presents new interviews with Temple Grandin, the autistic scientist, and the artist Shane Fistell, who has Tourette’s Syndrome, both of whom featured in Sacks' books and retain huge admiration for the neurologist.

For me, some of the archive footage of profoundly disabled patients being ministered to by Sacks verges uncomfortably close to the freak show. But I find it hard to see Sacks simply as a patronising exploiter of disabled people simply for his own glory. He was patently eager to be acclaimed as a writer and respected as a scientist by his peers, but he also sought to understand his patients' lived experience. Setting Sacks' work in the context of the trauma of watching his beloved older brother descend into violent schizophrenia during his teens, his own repressed homosexuality and his own neurological quirks helps round out a complex portrait of a complex man.

Add comment