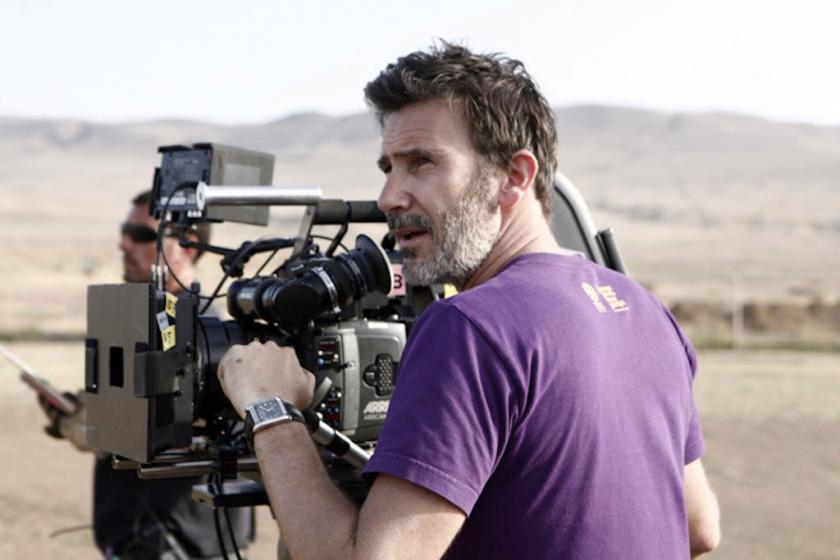

French director Michel Hazanavicius made a name for himself with his OSS 117 spy spoofs, Nest of Spies (2006) and Lost in Rio (2009), set in the Fifties and Sixties respectively and starring Jean Dujardin as a somewhat idiotic and prejudiced secret agent. But it was with The Artist in 2011 that he hit the jackpot, marrying his gift for period recreation with a story of genuine depth and warmth. A black-and-white silent movie about the silent era itself, starring Dujardin alongside Hazanavicius's wife and frequent collaborator Bérénice Bejo, The Artist was an irresistible crowd-pleaser that won five Oscars, including best picture, director and actor.

In 2014 Hazanavicius came back to Earth with a bump, with his poorly received war film The Search. Though he’s seemingly lost none of his confidence, daring now to make a biographical film about not just a fellow filmmaker, but the iconic, brilliant, controversial, formidable old grouch, Jean-Luc Godard.

Redoubtable is based on the novel Un an après (One Year Later) by Anne Wiazemsky, the actress and writer who was married to Godard between 1967 and 1979. Book and film focus on one year, 1968. Stung by the reception to his political La Chinoise, which starred his new love Wiazemsky as a Maoist student, Godard launches into a period of soul-searching and radicalisation that he intends to funnel into his filmmaking. While his friends despair, the political youth that he covets hold him in contempt. And the hitherto charming husband becomes a bit of a jerk.

Louis Garrel, who plays Hazanavicius's Godard (pictured below, with Stacy Martin as Anne) has an apt perspective on the film. “This is the third time I’ve acted in a film about May ’68,” the actor says. “Bernardo Bertolucci’s approach in The Dreamers is phantasmagorical. My father Philippe Garrel’s Regular Lovers is poetic… Michel’s point of view is different again: he uses the codes of dramatic farce or Italian-style comedy; his point of view is both critical and tender... After all, Godard himself, in replying to a question about May ’68 and cinema, said it was a subject for Jerry Lewis.”  THE ARTS DESK: What was your inspiration for the film – Godard, or Anne Wiazemsky’s book?

THE ARTS DESK: What was your inspiration for the film – Godard, or Anne Wiazemsky’s book?

MICHEL HAZANACIVIUS: Completely by chance, I had to take a train and had forgotten the book I was reading at the time. I looked for one at the station and found Un an après and immediately saw a film.

Anne Wiazemsky wrote two books about her love story with Jean-Luc Godard. Une année studieuse talks about the beginning of their relationship, the way this charming yet awkward guy takes his first steps in a great Gaullist family – Anne being François Mauriac’s granddaughter – until the reception of La Chinoise at the Avignon Festival in 1967. Un an après talks about May 1968, the crisis Godard went through, his radicalisation, the disintegration of their marriage, up until their break- up. I was very touched by their story. I found it original, moving, sexy and simply beautiful.

Redoubtable comes in the main from Un an après. When I contacted her by phone, Anne Wiazemsky had already turned down several offers. She had no desire for her book to become a film. Just before we hung up, I told her it was a real shame and all the more so as I’d found the book so funny. She reacted immediately and said she too thought it was funny, but no one had ever said so. And that’s how it all started.

What did you learn most of Godard in the books?

They’re not about his work, really, they're about the man and their intimacy. I discovered a more charming man in the books than I expected, I have to say. I had seen him as a mean man, as someone very harsh with people, and here I saw a charming man. Of course, because it's a love story.

At first glance, a film about Godard seems a surprising move for you?

When I started on the script, my friends would ask me what I was working on and I would say it's a movie about Jean-Luc Godard, and they were concerned for me. Because I'm coming from comedy, OS-117, and then a silent movie [The Artist, pictured below], and then a movie about Chechnya, and then I go to Godard. So what's going on? What next?!  But I don’t consider this film so unexpected or even atypical. One of the things that interested me and helped me to believe that this film was possible, was that Godard, while being a great artist with a difficult reputation – I’m talking about his films, but also about him as a character – can all the same be seen as a pop culture icon. He’s one of the key figures of the Sixties, as much as Andy Warhol, Muhammad Ali, Elvis or John Lennon. He belongs to the popular imagination.

But I don’t consider this film so unexpected or even atypical. One of the things that interested me and helped me to believe that this film was possible, was that Godard, while being a great artist with a difficult reputation – I’m talking about his films, but also about him as a character – can all the same be seen as a pop culture icon. He’s one of the key figures of the Sixties, as much as Andy Warhol, Muhammad Ali, Elvis or John Lennon. He belongs to the popular imagination.

He has also never been bland, never tried to be “nice”, which allows a great narrative freedom. I’m not condemned to eulogise him, since this isn’t the response he himself tries to elicit. But mostly, and we tend to forget this, his films – and also, he himself – could be extremely funny.

Besides, and this is essential, it is their love story that attracted me first of all. In his search for ideals and the love of revolution, this man will destroy everything around him: his idols, his background, his work, his friends, but also his relationship, and will end up destroying himself. And Anne will be the witness of his downward spiral.

Anne Wiazemsky died shortly before the film was released in France, but she’d seen it when it premiered in Cannes. What was her response?

She loved the movie. She really recognised the portrait of her and Godard and she was proud of it. And I'm proud as well that we went to the Cannes festival together. She knew she was ill, actually. I didn't, she didn't tell me. But I think she had a great moment going there.

Did she recognise herself in the film?

No, of course not, for two reasons. I’m not sure even Godard will recognise himself, but I tried to find a certain truth about him. For Anne, it's different. I considered that the character people would focus on was Godard, and that they don’t know Anne, really, so with her I tried to make the best character for my movie – a character who was a mix of his female characters of the Sixties, because it was the end of the Sixties and she represented the period, in a way. And just to show what, for him, was at stake.

Do you mean to say that the way that you shot her, including quite a lot of nudity, reflected the way he shot women?

Yeah, exactly. You know the French serial killer, Landru, in the 19th century: Chabrol made a movie about him [Landru, 1963]. He would marry a woman, kill her, cut her up then put her in a closet. Many times I thought of Jean-Luc Godard as Landru, because he literally would cut women with his shots – shooting the feet, shooting the legs, shooting the bottom. Taking that approach was a way of putting him in his own cinematographic universe. As for the nudity, there are two male characters who are naked in the movie and one woman. I try to be fair. She's naked, but not that much.

Is it a given that he’s an important director for you?

Now more than he used to be, because I made a movie about him and I put my feet in his shoes in a way. When you write a character you try to take in his point of view, you want to defend him, even if you keep your distance.  Which of his qualities as a filmmaker do you admire, maybe have discovered anew?

Which of his qualities as a filmmaker do you admire, maybe have discovered anew?

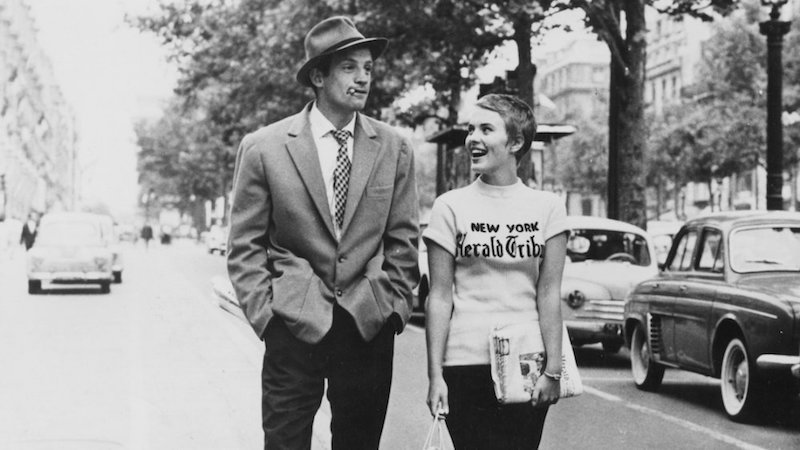

I had a very simple relation to his work. I really love the first decade, the Sixties, Breathless [pictured above], the Anna Karina films, I don't give a shit about the rest – it's boring, I don't get it, I understand vaguely what he wants to do but I'm not interested. And that was it.

With Redoubtable I was working at maybe the most interesting period of Godard for me, which is this moment, in 1968, when he killed everything that he'd done before – which everybody more or less loves – and starts to go in that direction that very few people love. It's the fracture. So, I had to study what was before and what was after.

What I love in the first period is the freedom, and how with this freedom he pushed the limits of traditional cinema – working with actors, how he treated cinema as sound and image, creating sensation, feelings, putting a lot of charm in the movies; it's creative, it's innovative, it's funny, it's totally connected to the period.

This is interesting. Those films are not realistic, the actors are not playing in a naturalistic way. But now, when you look at the movies of the Sixties, you watch the so-called realistic movies, from Truffaut, Chabrol, whoever, these movies look very theatrical, and it’s with Godard that you have a real flavour of the reality of the Sixties. It’s really funny. Fifty years later it's the exact opposite.

Also, it's like the audience is part of the process: I feel that he cares about me, he wants me not to be bored. And I like this. After that I felt that he didn’t care about me, at all. He is looking for something that’s personal to him.

But I’ve changed my mind. Now I consider what came later is an avant-garde attitude, and maybe it's the ultimate state of freedom. And I consider that he accepted that he would lose himself, he dived into the unknown, not knowing what he was going to find, and he got lost. He made these very strange movies in the Seventies. Do you know this movie Le vent d'est (Wind from the East), it's supposed to be a western with Gian Maria Volonté, it's so weird. But this is how he became Jean-Luc Godard – losing himself is how he found himself.

You have that line in your film.

Exactly, that's where I ended the movie. I thought that maybe some people would think that the movie was a judgement, because I present a lot of antagonists against him. But it’s not a melancholic movie. At the end I wanted him to have the last word – he always wants the last word: "You know what, fuck you. You might think I betrayed cinema, you might think I made the wrong decision, but this is my life. And because I made the wrong decision doesn't mean I was wrong. This is my path." What about his politics?

What about his politics?

Godard has said some very mean and stupid things in his life. As a political thinker I think he's really not good. He said a lot of things about Jews for example, and I'm Jewish. I don't think he's anti-Semitic, but I think he has a kind of obsession with the Jews, and this obsession could blind me a little bit to the man himself. But when I read the book, and when I worked on the research, I saw an intellectual process, and how he became so radical. And this process was very interesting to me because now, here in France and in a lot of Western countries, a lot of people – and a lot of people from the intelligentsia – become radical, with a "you're with me or you're against me" way of thinking about the world. You're my friend or you're my enemy.

Louis Garrel is superbly cast.

I chose him from the very beginning, because he has this very intellectual charm. He doesn't have an animal, sexual charm, he's much more intellectual. So I thought that would fit perfectly with Godard. Also, because he's handsome, it's a good equivalence to charisma, because Godard was maybe not handsome but he had a lot of charisma.

When I called Louis he was afraid of it, because he worships Godard. Then I sent him the script, and he realised it was a comedy, with a lot of distance, so he accepted.

And then we started to work. I knew he could make a perfect impersonation of Godard, but that was not the goal: to be perfect it has to be always the same, so it’s not living anymore. And also Louis didn't want to do it. He wanted to do it with his own voice, but that didn’t make sense for me either, the audience needed some signal they are watching Godard. So we tried to find a middle way, one which would humanise him.

And then the wig. The wig was a huge thing. When you have such beautiful hair like Louis Garrel, it's a blasphemy just to cut it. Maybe it's a blasphemy to make a movie about Godard, but to cut Louis Garrel’s hair is even worse. So that was a huge fight during the prep.

At the same time as you were presenting a portrait of this very reclusive figure in Cannes 2017, the festival also premiered Agnès Varda’s new documentary Faces Places, in which we think we’re going to get a glimpse of Godard, but then we don’t. They’re old friends from the nouvelle vague. Was he being mean to her?

I don't think so. I really love Agnès Varda and I love [her co-director] JR as well, I think their movie is lovely. But Godard co-directed that scene – not literally, but by not opening his door he created perhaps the best sequence in the movie. If he had opened the door, they would have had a discussion around the kitchen table. It would not have been this wonderful sequence of cinema.

Did Godard react to Redoubtable?

No. I'm not sure he saw it. And I'm not sure he cares about it. I think he's far way far from all that.

- Redoubtable is released in cinemas on 11 May

Add comment