There are moments in Straight Shooting (1917), the first feature directed by John (then "Jack") Ford, when its star Harry Carey (1878-1947) exudes a naturalism that the famous Western actors who followed him, most notably John Wayne, strove to emulate.

When Carey's character Cheyenne Harry is looking confidingly at the camera, his surly almost-smile is millimetre-perfect in its grudgingness and sense of the ironic. His unsteadiness and glazed expression when drunk convey that bizarre mix of hyper-selfawareness and dimmed comprehension everyone knows when they've had two or three too many. In the rhetoric-heavy era of silent cinema acting, Carey was a marvel of minimalism – unlike William S Hart, his peer (and fellow New Yorker) in seminal silent Westerns.

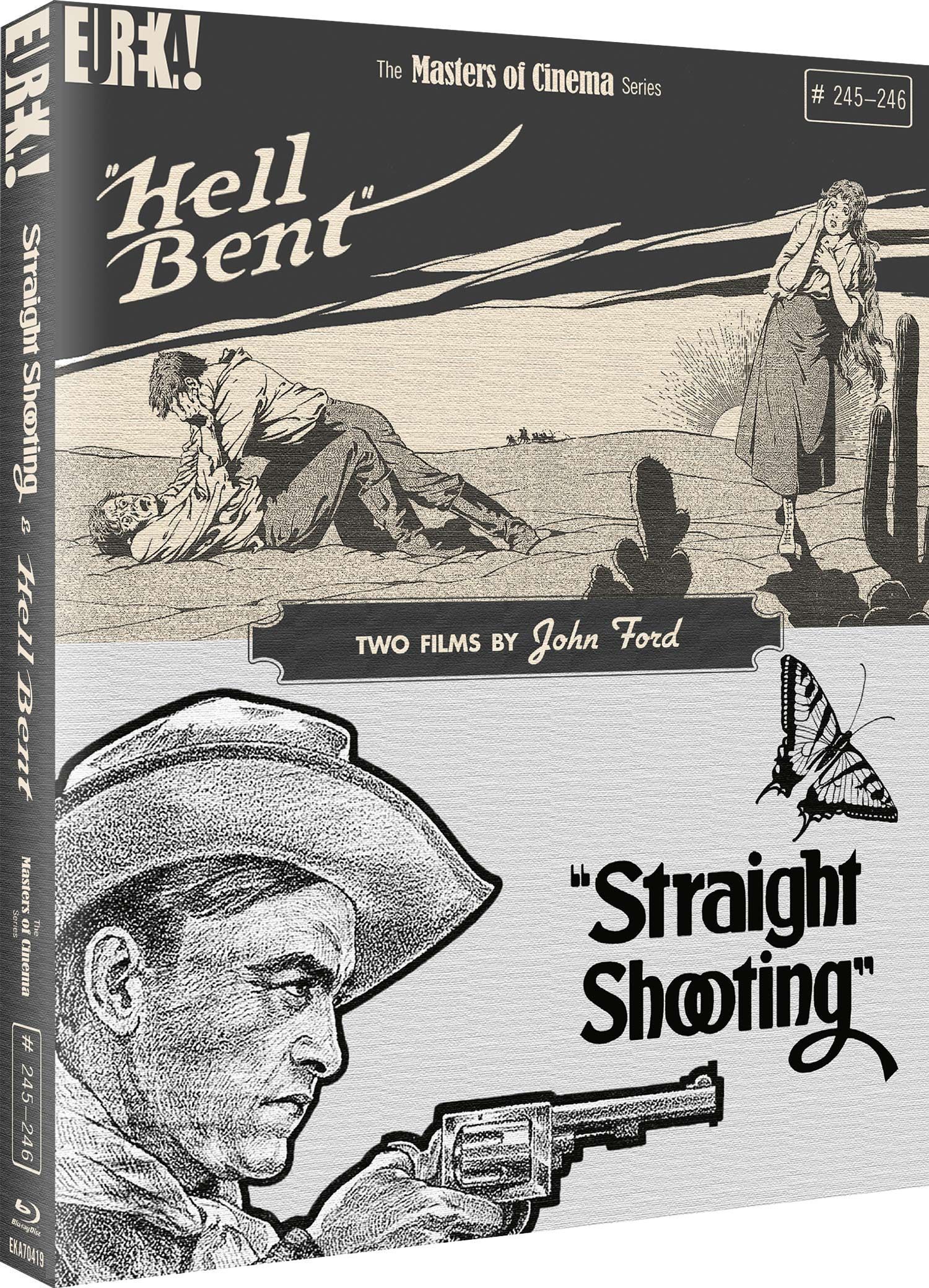

Straight Shooting and the comic Hell Bent (1918), pristinely restored in 4K and paired on this Masters of Cinema Blu-ray, were the 13th and 20th of Carey's 30 frontier adventures as Cheyenne Harry, 18 of them directed by Ford, few of which have survived. The character was the archetypal "good bad man", a robber and sometime killer, one often redeemed by an awakened conscience and the love of a good (that is, virginal) woman.

In the range war drama Straight Shooting, which anticipated Shane's representation of the 1889-1893 Johnson County War, Harry is first seen peering out of a hole in a tree – bearing a new $1000 reward poster for him – with a Cheshire Cat grin. Though currently working as a gunman for a ruthless cattle baron (Duke R Lee), Harry is pricked by the murder of an innocent young settler to side with the grieving father and sister, Joan (Molly Malone). He surprises himself by falling for the girl, whose feelings for him grow after he rescues her from the cattle baron's thugs.

In Hell Bent, drifter Harry matter-of-factly rides his horse into a saloon and a hotel room above it. He bonds with the occupant, Cimmaron Bill (Lee), after they sing "Sweet Genevieve" together and share the bed, Harry hiring on the next day as the saloon's bouncer. Bill's affection for his new friend is comically but frankly wistful, possibly a mark of Ford's sentimental attachment to Carey. (Ironically, gibes about Ford's masculinity made by Joe Harris, a member of Ford's stock company who lived on Carey's ranch, contributed to Carey and Ford's professional split in 1921.)

In Hell Bent, drifter Harry matter-of-factly rides his horse into a saloon and a hotel room above it. He bonds with the occupant, Cimmaron Bill (Lee), after they sing "Sweet Genevieve" together and share the bed, Harry hiring on the next day as the saloon's bouncer. Bill's affection for his new friend is comically but frankly wistful, possibly a mark of Ford's sentimental attachment to Carey. (Ironically, gibes about Ford's masculinity made by Joe Harris, a member of Ford's stock company who lived on Carey's ranch, contributed to Carey and Ford's professional split in 1921.)

Harry is nonplussed when Bess (Neva Gerber), the virtuous young townswoman he admires, is forced by the laziness of her brother (Vester Pegg), who joins an oulaw gang, to become a dancer at the saloon to support their sick mother. Like Straight Shooting's craven sheriff, the brother in Hell Bent is a well-dressed dude – soft, feckless, a symbol of urban decadence – whom Ford contrasts with the scruffy, earthy, empathetic Harry. Descended from James Fenimore Cooper's Hawkeye (aka Natty Bumppo), Harry was succeeded by chivalrous, hardy (and lethal) Westerners like the outlaw Ringo (Wayne) in Stagecoach (1939) and the horse trader Travis Blue (Ben Johnson) in Wagon Master (1950).

Ford and Carey shared the Victorian morality of DW Griffith, who had helped launch Carey's film career. In rescuing Bess from a saloon mob and later the suave outlaw boss who kidnaps her (the aforementiioned Joe Harris) – leading to an exciting desert finale – Harry protects the girl's "honour"; he cradles her in his arms and carries her from the saloon as Ethan Edwards (Wayne) cradles his teenage niece Debbie (Natalie Wood), a Comanche captive and squaw, at the climax of Ford's The Searchers (1956), rescuing her from what he perceives would be further defilement. Similarly, Ringo and Travis court the fallen women Dallas (Claire Trevor) and Denver (Joanne Dru), respectively, and deliver them from what Stagecoach's alcoholic doctor (Thomas Mitchell) calls "the blessings of civilisation".

Women for Ford meant not only virtue, but the tug of home and permanence. Harry is so torn between staying to marry Joan and continuing his rootless ways, however, that Ford shot and incorporated two endings for Straight Shooting, the romantic one possibly foisted on him by Universal Pictures. Ford resolved the male existential dilemma at the end of The Searchers by having Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter) enter the ranch house of his future bride (Vera Miles) and her parents while Ethan turns away into the desert after pausing in the doorway, his left hand clutching his right arm at the elbow – his and Ford's famous salute to Carey, who was given to that vulnerable pose in his films, Straight Shooting among them.

Carey's widow Olive and their son Harry Jr, both actors in The Searchers, were inside the ranch house with Ford when he made that shot. The Blu-ray includes a talk on Carey by the critic Kim Newman, who concludes that Ford, who also paid homage to Carey in 3 Godfathers (1948), was prompted to honour him belatedly because of the guilt he felt for neglecting the actor professionally after 1921, their sole talkie collaboration being The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936).

Twenty-three when he directed Straight Shooting, Ford was already demonstrating his genius for pictorialism. He used doorways and rivers as separating devices charged with moral and emotional resonance. Winchester Repeater-toting Harry's one-on-one gunfight with a former drinking partner (Pegg) – they stalk each other round a single building in a deserted street – is brief and authentic-seeming, a far cry from the fake ritualism of most Western duels. The interior shot of Joan's mounted beau (Hoot Gibson) hurtling toward the open doorway of her house was replicated by Ford in the shot that introduces Martin in The Searchers. (Pictured below: Neva Gerber in "Hell Bent")

Both of these silents feature precipitous action shots of horsemen riding pell-mell on their paltry errands against and within implacably Olympian scenery – a deep natural bowl into which an army of outlaws descend (you wonder it doesn't close over them), a cliff from which a stagecoach topples, its train of spooked horses galloping past the wreck moments after taking a hairpin bend. Ford hadn't yet discovered Monument Valley, but in Straight Shooting and Hell Bent he evocatively uses Beale's Cut Stagecoach Pass, Santa Clarita, California, the towering divide he (supposedly) had Tom Mix's horse leap in Three Jumps Ahead (1923).

Both of these silents feature precipitous action shots of horsemen riding pell-mell on their paltry errands against and within implacably Olympian scenery – a deep natural bowl into which an army of outlaws descend (you wonder it doesn't close over them), a cliff from which a stagecoach topples, its train of spooked horses galloping past the wreck moments after taking a hairpin bend. Ford hadn't yet discovered Monument Valley, but in Straight Shooting and Hell Bent he evocatively uses Beale's Cut Stagecoach Pass, Santa Clarita, California, the towering divide he (supposedly) had Tom Mix's horse leap in Three Jumps Ahead (1923).

Ford's cameraman Ben F Reynolds (partnered by George Scott on Straight Shooting) brilliantly foregrounded objects like lamps to increase the depth of field in interiors. At the start of Hell Bent, a successful novelist encouraged by his publisher to create more morally complex characters ponders his framed copy of Frederic Remington's 1897 drawing "A Misdeal" – showing the body-strewn aftermath of a saloon card game – which comes magically alive with scurrilous card cheat Harry at its centre.

The disc extras are impressive. Newman's seemingly extemporised on-camera piece on Carey is complemented by pithy, nuanced essays on each movie by Tag Gallagher, author of John Ford and His Films (1986), the richest critical analysis of the master's oeuvre. Joseph McBride, whose biography Searching For John Ford: A Life (2001) is unsurpassed, provides engaging full-length audio commentaries. During his assessment of Straight Shooting, McBride recalls how as a young man he sent a screenplay he'd written about a Harry Carey-like saddletramp to Wayne, who was apparently offended McBride thought he'd want such a part.

Add comment