Two hundred years ago in Durham taverns you could find men in wooden clogs clattering on the tables, with their mates pressing their ears to the underside of the surface. Meanwhile, at the other end of the world, African slaves with bare feet were shuffling on dirt with metal bottle caps held between their toes. Now picture a Mediterranean gypsy dancing of sorrow and pain with swirling shawls and angrily pounding heels. Three quite different scenes, different places, different eras, but all rooted in one human impulse, common the world over.

Rhythm, in its expressive sense, has been quietly receding from modern Western life, as the regulated throb and hum of the electronic age swept syncopation and surprise aside. And , with flamenco, Irish, African and Indian percussive dance, Stomp and Tap Dogs all dependably pulling in the crowds. Sadler's Wells has become a frequent host for the rising tide of percussive feet, with the next two weeks pulsating to Spain's rattles and yowls at the London Flamenco Festival and South African dance beats at UMOJA.

How different these pulses feel, geographically as well as emotionally - the pictures they evoke crisscross the world from Andalusia to Appalachia, from Lucknow to Londonderry, from Newcastle to New York. Many of them are almost forgotten: South African gumboot, Northumberland rapper dancing, lindy-hop. Yet there are powerful family relationships here, traced by the great migrations of human beings around the globe, taking their cultural individuality, their dancing, their music, their physical rituals, with them.

Clogs became everyday work footwear, people danced on hard factory floors, imitating the rhythms of the machines

“Percussive dance is music, wherever it comes from. As a dancer, in any of these styles, I‘m a musician, because the percussion comes first, then dance,” says Ira Bernstein, a multi-skilled New Yorker who is master of jazz tap, Appalachian clogging (see Bluegrass video at end), Irish and Canadian step-dancing, English clog and South African gumboot. Bernstein reckons that constant rhythm in everyday life caused the explosion of rhythmic step-dancing around the West in the past 200 years and the emergence of the 20th century's ubiquitous tap-dance. Dancing, he says, tells human history.

“Many percussive dances are work dances. The South African boot dance (see Cape Town video), originally a sugar-cane plantation dance, was taken up by miners wearing wellies in the mines. English clog dances were associated with the Industrial Revolution - clogs became everyday work footwear, people danced on hard factory floors, imitating the rhythms of the machines.”

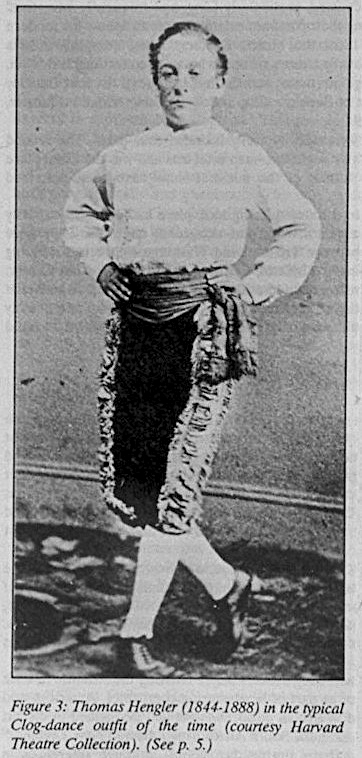

Percussive riffs led to rivalry between men - a major force of Western percussive dancing. Irish step-dancing has become probably the most virtuosic foot dance in the world through its honing by a global championship circuit that takes in Australia as well as Florida. Chicago's Michael Flatley was a Guinness world record-holder when he used Riverdance to sweep Irish dancing for the first time into the field of popular theatrical entertainment. But more than 100 years before him Irish stepdancer Thomas Hengler was the most popular dancing act in New York (pictured right, courtesy Harvard Theatre Collection).

Percussive riffs led to rivalry between men - a major force of Western percussive dancing. Irish step-dancing has become probably the most virtuosic foot dance in the world through its honing by a global championship circuit that takes in Australia as well as Florida. Chicago's Michael Flatley was a Guinness world record-holder when he used Riverdance to sweep Irish dancing for the first time into the field of popular theatrical entertainment. But more than 100 years before him Irish stepdancer Thomas Hengler was the most popular dancing act in New York (pictured right, courtesy Harvard Theatre Collection).

Today competition remains remains the vital force that keeps thousands of Irish floors worn down by the thunder of boots, high-switching legs and crisscrossing feet that makes Irish step so dazzling. In this kind of speed-dancing, arms get in the way - it's got nothing to do with nuns forbidding carnal touching.

What tells a remarkable tale of the universality of human impulses is how well Irish step dance and English clog dance travelled, along with their fiddles and accordions - Canadian step dance is a variant of them; so is Appalachian clog. As the steps travelled to larger spaces, so the arms became more sociably expressive. And what a child resulted when fast rhythmic white boots met swaying, improvisatory black soul - tap.

Tap-dancing is far older than the Hollywood confection whipped up by Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly in the 1930s and ‘40s, according to tap specialist Tobias Tak. “Tapping originated in sand dances,” he says, “African slaves in America shuffling barefooted, singing work songs and homesick blues, who then put metal bottle tops between their toes to make a noise on hard dirt.”

In time they got shoes, and they began noticing the dancing of Irish and English immigrants with their fleet aerial virtuosity, and they hammered the tin caps onto the shoes to up the percussion as they experimented. With their profound, deep-footed stomp and swaying songs, Africans loosened up the strict Northern European posture - and hoofing was born (see Gregory Hines video). Solo tap could be anything from thrillingly competitive to improvisatory private blues.

Meanwhile another hybrid was forming out East, where travelling gypsy blacksmiths who drummed their heels like their hammers met North Indian Kathak balladeers, and gave the world flamenco. Although flamenco needs high heels and Kathak dancers wear bells round the ankles of bare feet, the two forms are very similar. Both contrast fast, earthy foot-percussion with highly expressive arms, describing powerful pictures. And both dance forms are sensual and spontaneous in rhythm in a way that few of the European step and clog traditions are. They also express a much wider range of emotional stories, love, lust, death, transfiguration, prayer.

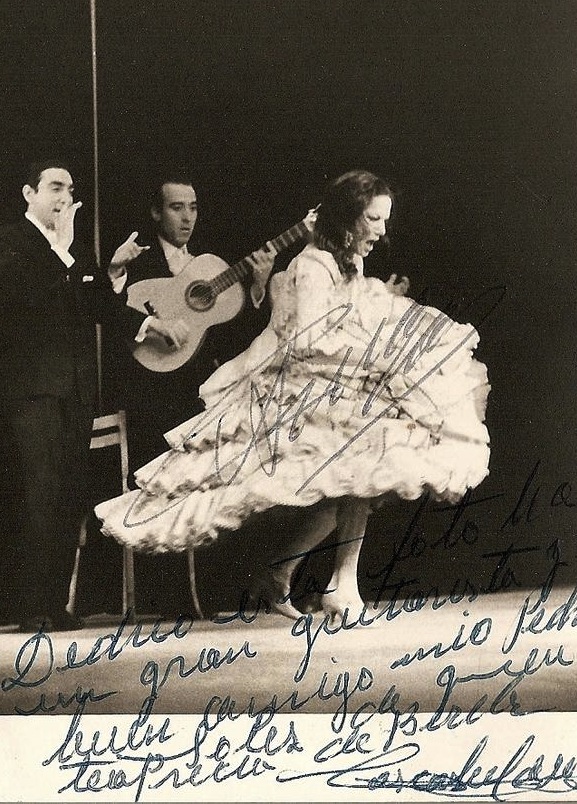

While rhythm from the step-dancing traditions tends to be regular, four-square, dictated by a band, in flamenco and kathak the rhythm is led by the dancer, who improvises much of his or her show with a highly sophisticated musical sense. Each of these dance traditions looks for its essence in its music - flamenco with its emotional songs, kathak with its bubbling tabla. The flamenco framework may be 12 beats to a bar, but a dancer will divide that up into threes, fours, fives, according to her mood. (The legendary Carmen Amaya pictured left, courtesy Pedro Soler)

While rhythm from the step-dancing traditions tends to be regular, four-square, dictated by a band, in flamenco and kathak the rhythm is led by the dancer, who improvises much of his or her show with a highly sophisticated musical sense. Each of these dance traditions looks for its essence in its music - flamenco with its emotional songs, kathak with its bubbling tabla. The flamenco framework may be 12 beats to a bar, but a dancer will divide that up into threes, fours, fives, according to her mood. (The legendary Carmen Amaya pictured left, courtesy Pedro Soler)

The challenge for a kathak specialist is not foot virtuosity for its own sake but to master exactly the sound of his or her bare foot striking the floor, and the timbre of the ankle-bells, which may entwine more than one rhythm at a time. Unlike the other great Indian dance form, bharathanatyam, with its Hindu religious origins, kathak is a secular tradition that has constantly swallowed other influences. Now kathak is not only being influenced by Western popular music and tap but feeding stories back into unlikely new places - such as British contemporary dance, where rhythm has seemed very far away.

The remarkable artistry of Akram Khan (see video), celebrated now as a contemporary choreographer of stunning variety, is deeply embedded in the range of his virtuosity and understanding of kathak, the form in which he began, and whose stories of the gods have become his dramatic materials too. Increasingly, with the sweeping of Indian and Asian musics through British musical culture, dancers are being challenged to go back to the very origins of their dance form - expressing not just beats, but the constantly altering rhythms of work, love, entertainment and survival.

Now watch the videos...

South African gumboot: Performers in a Cape Town street

New York hoofing: Gregory Hines

Northern England: Northumberland Rapper Dancing

North American: Bluegrass Clog Dancing, 1964, US North Carolina

Show-tap: The Nicholas Brothers in what Fred Astaire called the greatest dance ever filmed, from Stormy Weather

Flamenco: An extract from Antonio Gades's Fuenteovejuna

Kathak: Akram Khan on The South Bank Show describing and performing kathak

- Sadler's Wells Flamenco Festival runs from 7-19 February at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London - 7 February, guitarist Vicente Amigo; 8 & 9 February, dancer Manuela Carrasco; 10 February, Olga Pericet Company; 11 & 12 February, Garcia Lorca gala; 13 February, guitarist Gerardo Núñez & dancer Carmen Cortés; 14-16 February, Antonio Gades Company’s Fuenteovejuna; 17 & 18 February, dancer Rafael Amargo; 19 February, cantor José Mercé

- UMOJA is at the Peacock Theatre, London till 19 February

- Akram Khan's Vertical Road is performed at The Hawth, Crawley on 23 February; and also at Montclair University, New Jersey 8-12 February, Oslo's Dansens Hus 2-4 March, an extensive French tour 7-30 March, then Colombia, Switzerland and Austria into May. Complete touring schedule here

- The interviews with Ira Bernstein and Tobias Tak took place in 1996

Add comment