Martha Argerich Edition (EuroArts)

Martha Argerich Edition (EuroArts)

Almost eight hours of Martha Argerich on film. What a glorious prospect! This six-DVD set mostly consists of recordings of live concerts. The set was released to celebrate the great Argentinian’s 80th birthday last month. Again and again in performance, she finds depths, colours and transcendence that simply stop you in your tracks. There is a Prokofiev 3rd Concerto with the LSO and Previn recorded in Croydon in 1977, where she switches from the most delicate of dream sequences to playing which is forceful, propulsive, totally commanding. And there are those occasional precious moments when the cameras have managed to catch not just the exuberance of her playing, but also her capacity to find joy in it. The grateful, amazed, radiant smile she gives to Charles Groves right at the end of an exuberantly, almost illegally fast performance of the Tchaikovsky concerto at the Guildhall in Preston (!) in 1977 is to be treasured. And witness her mischievous joy as she launches into two encores in Warsaw in 2010 before the audience has had the chance to sit down. The second, a coruscating “Traumeswirren” from Schumann’s Op. 12, is unforgettable.

The very short essay in the booklet by German journalist Juliane Moghimi mainly focuses on drawing a few simplified conclusions from Bloody Daughter an intimate, 95-minute portrait of the pianist and her patchwork family which Argerich and Stephen Kovacevch’s daughter Stéphanie made and narrated in 2012. The film comes and goes on the internet, currently freely available on the Euro Arts Channel. It's interesting to watch because it gives some biographical context – but probably only once.

The music has been captured in a range of circumstances and styles. The most self-consciously "filmic" is the Abbado CD of four Prometheus works (Beethoven, Liszt, Scriabin and Nono – Argerich is only in the third of those) which gives us everything from weirdly colour-processed footage of the orchestra to confusing image superimpositions, and even a few inexplicable outings into a Kenyan game park. And we could have done without some members of the audience at the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires taking the law into their own hands at a duo recital Argerich plays with Daniel Barenboim: during announcements they intervene with some cringe-making heckling, which Barenboim, clearly irritated, deals with imperiously.

Argerich’s art is always alive to the moment. That is its joy, but we are too often at the mercy of what camera placement, cameramen and film editing have either chosen or been able to capture. Sometimes the camera work is sensitive to the logic and the progression of the music. The Croydon and Preston cameras are all well-placed and one feels grateful that all involved have done their work quite so well. The 2010 Warsaw camera placement switches back and forth from some well-placed cameras to one pointlessly placed in a cricked-neck position right under the keyboard. And for the most recent concert, a superb 2020 duo recital with violinist Guy Braunstein in the Boulezsaal in Berlin, the producer flicks randomly as if on auto-pilot from one poorly placed camera to another. Musically stunning, yes but more or less unwatchable. This is a set in which Argerich’s artistry shines through gloriously, but production quality is far too variable.

Sebastian Scotney

Dutilleux: Le Loup Sinfonia of London/John Wilson (Chandos)

Dutilleux: Le Loup Sinfonia of London/John Wilson (Chandos)

Henri Dutilleux’s ballet Le Loup is an early work, premiered in 1953. Its scenario, co-devised by playwright Jean Anouilh, tells the tale of a young bride who unwittingly marries a wolf. Dutilleux was immediately taken with the idea, creating a thematically complex one-act work which will surprise anyone who’s only heard the composer’s refined, spare mature music. Le Loup is a new addition to a long line of colourful French ballet scores; if you’ve responded to works as different as Ravel’s Daphnis or Poulenc’s Les Biches, you’ll find plenty to savour here. The orchestral writing is terrific: sample the brassy circus opening, replete with trombone pedals and galloping brass, and the sequence of dances in the second tableau, one of which recalls Prokofiev’s Cinderella. Dutilleux deploys his large forces (you wonder how an ensemble this big could fit into the pit) with such skill; I love the use of bass piano notes to add weight to dense chords. Things end badly, alas, the wolf hunted and killed with his bride, Dutilleux replaying the first tableau’s trumpet theme as a sentimental funeral song. Wonderful stuff, handsomely played and recorded here. There’s a tantalising mention in Caroline Potter’s notes of a follow-up, a ballet based on La Belle au bois dormant which Dutilleux destroyed after a muted reception to its first performance.

This disc serves as a reminder of John Wilson’s wide range. Yes, he’s great at Broadway musicals and MGM scores, but he’s recorded Eric Coates and Richard Rodney Bennett with exactly the same care and attention to detail. The couplings are exquisite: orchestrations by one-time Dutilleux pupil Kenneth Hesketh of three early solo wind pieces. Each is wonderfully realised and impeccably performed. Flautist Adam Walker is affecting in the limpid Sonatine, while oboist Juliana Koch gives us the Sonate for Oboe and Piano. As with the Hindemith sonatas discussed below, each is so well-written, alert to each instrument’s expressive possibilities. I’m especially fond of the Sarabande et Cortège for bassoon, its quirky march my earworm of the week. The booklet interview with Hesketh is a good read, mentioning Dutilleux’s reluctance to discuss his early music as well as his conviviality.

Hindemith: Wind Sonatas Les Vents Français (Warner Classics)

Hindemith: Wind Sonatas Les Vents Français (Warner Classics)

That Hindemith was a viola virtuoso is widely known. He could also play just about every orchestral instrument and dabbled in some obscurities too, writing music for the Trautonium and the hecklephone. Wind players will know and love these five solo sonatas already; having them collected on a single disc, performed by a starry line-up, will hopefully prompt the rest of you to have a listen too. Musically, they’re incredibly rewarding, and it’s striking how perfectly each sonata is attuned to the characteristics and quirks of its solo instrument. The earliest piece here, the 1936 Flute Sonata, has a few austere corners but is readily accessible, a perfect example of Hindemith’s mature style. There’s an abundance of dense counterpoint, the pianist often faced with some tricksy writing, and the harmonic language, however complex, has a delicious knack of resolving on a familiar-sounding chord just when you’re starting to scratch your head. Emmanuel Pahud plays it here, brilliantly partnered by Éric Le Sage, whose lucid accompaniments are a consistent pleasure. And François Leleux in the Oboe Sonata is terrific, the music’s spikiness and lyricism captured with such wit. Paul Meyer’s liquid slurs are unobtrusively impressive in the Clarinet Sonata’s opening movement, and he’s relaxed and joyful in the little finale.

Gilbert Audin’s account of the tiny Bassoon Sonata is a delight; anyone unsure about this anthology should hear him and le Sage at the start of the second movement, high bassoon singing over a rocking piano accompaniment. And instead of the usual Horn Sonata, Radovan Vlatković plays the less familiar Sonata for althorn, intended the German equivalent of the Eb tenor horn used in UK brass bands. Richly melodious, the surprise comes just before the finale, the performers instructed to recite a poem about the horn. We hear a plea “to conserve those things of permanency, peace and heartfelt meaning”, and it’s a wonderful moment, though I’d have preferred Vlatković and le Sage to have done the speaking rather than a pair of (admittedly decent) actors. Still, a lovely disc.

Mozart Momentum 1785 Leif Ove Andsnes, Mahler Chamber Orchestra (Sony)

Mozart Momentum 1785 Leif Ove Andsnes, Mahler Chamber Orchestra (Sony)

Andrew Mellor’s booklet describes sees 1785 as the year in which Mozart “changed gear”, his improved financial circumstances giving him the breathing space to reduce his quantitative output of piano concertos whilst increasing their emotional and technical complexity. No. 20 in D minor still sounds disconcertingly modern, a 19th century concerto several decades before its time. Leif Ove Andsnes, directing the Mahler Chamber Orchestra, is on marvellous form, brilliantly blending the concerto’s lyrical and dramatic elements. And what superb orchestral support he secures, details like the plangent woodwind chords seven minutes into the first movement really telling. The finale’s shift to D major is marvellous here, the dash to the finish utter joy. Concerto No. 21 is a sunnier affair, Andsnes and orchestra making the second movement sound fresh and unfamiliar.

Best of all is No. 22 in E flat, Andsnes’ woodwinds and horns ringing out in the opening tutti, and the hunting finale full of colour and bounce. Good couplings too: Andsnes gives us a dark, probing reading of the K475 Fantasia in C minor and is joined by three of the orchestra’s principal players for the K478 Piano Quartet, a nicely balanced reading where the pianist never threatens to overwhelm the strings. And there’s a splendidly rich-sounding Masonic Funeral Music thrown in. All excellent, with a second, 1786-theme volume, coming next.

Prokofiev: Symphony No. 6, Myaskovsky: Symphony No. 27 Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko (Lawo Classics)

Prokofiev: Symphony No. 6, Myaskovsky: Symphony No. 27 Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra/Vasily Petrenko (Lawo Classics)

I remember being blown away by Neeme Järvi's Chandos recording of Prokofiev 6 in the mid-1980s, his first release with the then Scottish National Orchestra. I don’t think it’s been surpassed; Järvi's musicians play as if their lives are at stake and the engineering is incredible. Since then, this once-neglected symphony has almost entered the standard repertoire and here’s another new recording. Listen to Vasily Petrenko straight after Järvi and you quickly notice the closer recording balance and brusquer take on the opening bars, the engineering allowing us to pick out individual voices in Prokofiev’s thicker textures. Petrenko’s swiftness is arresting, the first movement’s fast 6/8 section whizzing by, and the ominous third theme’s reprise comes with some superbly menacing trombone chords. Impressive too is the “Largo”, despite an opening which never quite screams as Järvi's does. The Oslo principal trumpet really cuts through in Prokofiev’s sinuous melodies, and we hear the echoes of Cinderella’s clock music in the central processional. Petrenko’s finale starts incredibly brightly, making the clouds’ descent all the more distressing. And I do like Petrenko’s coda, refusing, as does Andrew Litton, to do the customary unmarked slowdown in the final bars. An impressive, sober performance.

And coupled with the final, 27th symphony by Prokofiev’s friend Nikolai Myaskovsky. Music of impeccable restraint and craft, but difficult to get one’s head around, Myaskovsky’s personality remains appealing; it is a mellow work with an exquisite slow movement and a rousing finish. Great while it lasts, but curiously unmemorable despite some handsome playing from the Oslo players. Buy this for the Prokofiev, and pick up Järvi's version if you don’t already have it.

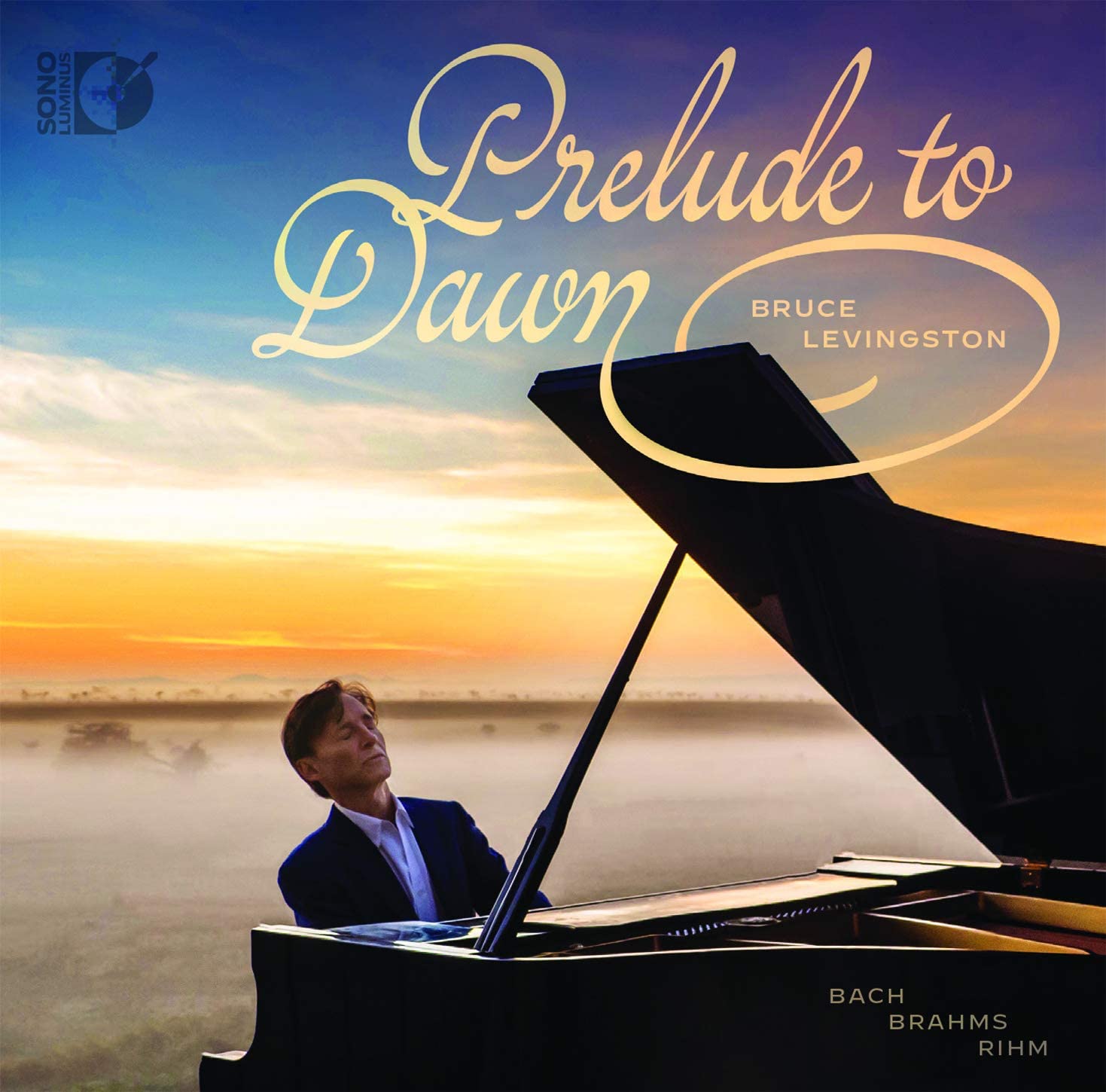

Prelude to Dawn – Music by Bach, Brahms and Rihm Bruce Levingston (Sono Luminus)

Prelude to Dawn – Music by Bach, Brahms and Rihm Bruce Levingston (Sono Luminus)

More a celebration of Bach's influence than a Bach recital, Bruce Levingston's latest disc opens with Brahms's inventive left-hand transcription of the Chaconne in D minor. Which, to my shame, I hadn't heard before. It's a remarkable reinvention, the only way in which he could enjoy "a greatly diminished but comparable and absolutely pure enjoyment of the work". The sense of strain, of a musician being pushed to the limit is, what gives the piece its power. Levingston's technique is as impressive as always but he never makes the piece sound glib, this performance feeling like a single take and ending with such finality that you're obliged to hit the pause button for a few minutes. A pair of Preludes by Wolfgang Rihm are imaginative 20th century responses to Bach, one a burbling toccata, the other a mournful processional.

Levingston's account of Bach's BWV 998 Prelude, Fugue and Allegro is all serenity and smiles, the "Prelude" softly-spoken and warm, preparing us for unshowy but immaculate accounts of the following movements. Sono Luminus's engineering helps: this is one of the best-sounding solo piano discs I've heard in ages. We get Busoni's transcription of Bach's Watchet auf, sweetly done, and Busoni's marvellous arrangement of Brahms's late Chorale Prelude in A minor, less austere and more consolatory than the organ original. Brahms's Theme and Variations in D minor makes for an apt closer. Levingston's restraint in the fifth variation is something to behold, as is his handling of the radiant major key close.

Add comment