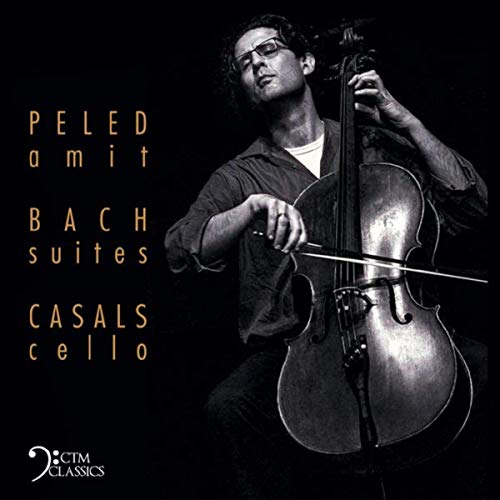

Bach: Cello Suites 1, 2 & 3 Amit Peled (CTM Classics)

Bach: Cello Suites 1, 2 & 3 Amit Peled (CTM Classics)

Pablo Casals famously recorded Bach’s six Cello Suites in 1936, his accounts largely responsible for changing public perceptions of these works. Previously regarded as little more than technical studies for students, Casals’ decision to include the suites in concert programmes transformed their status. If you know and love the Casals set, you'll want to hear this disc, if only for the fact that Amit Peled plays the 1733 Gofriller cello once owned by Casals and used back in 1936. As heard here, it does make a delicious, earthy sound, though that's arguably as much to do with Peled as it is with the instrument. In his words, “I’m happy to be the instrument’s servant… all I'm doing is riding in this terrific car at the moment,”

As modern performances go, these are highly desirable. Peled’s lightness of touch gives us a Bach who’s convivial, witty and only occasionally irascible. Preludes unfold as if they're being improvised on the spot. The faster numbers are exhilarating, my favourite being the gigue which closes the D minor suite. In Peled’s words, if a listener "wants to stand up and dance while I play, then I have done my job.”

Boris Lyatoshynsky Symphony No 3, Grazhyna Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Kirill Karabits (Chandos)

Boris Lyatoshynsky Symphony No 3, Grazhyna Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra/Kirill Karabits (Chandos)

Boris Lyatoshynsky's Symphony No 3 should have been officially premiered in Kiev in 1951. Alas, the Soviet authorities deemed the work unpatriotic and the performance was cancelled, Lyatoshynsky's subtitle “Peace shall defeat War” seemingly incompatible with Stalin’s belligerent, expansionist foreign policy. Despite the ban, conductor Natan Rakhlin showcased the symphony in an open rehearsal, though public outings were forbidden until Lyatoshynsky reworked the supposedly “bourgeois” finale four years later. Kirill Karabits restores the original ending. It's spectacular, a brassy hymn capped by pealing bells, the triumph heartfelt rather than glib. It feels all the more deserved after the angst in what's come before. Stylistically the music is fascinating, closer to Scriabin than Shostakovich. The opening movement’s dissonant opening is striking, and there’s an ear-tickling moment two minutes in where a series of snarling wind and brass chords are answered by groaning lower strings. What follows is turbulent, edgy stuff, undeniably exciting if short on memorable tunes. Lyatoshynsky's slow movement starts in delicate, rarified fashion before a percussive climax, and the scherzo's malice is tempered with an exquisite, bittersweet trio. All brilliantly played by the Bournemouth orchestra and captured in spectacular, wide-screen sound.

The epic ‘symphonic ballad’ Grazhyna dates from 1955. Inspired by the Polish writer Adam Mickiewicz’s narrative poem, it depicts which a plucky Lithuanian noblewoman battling Teutonic knights before meeting a tragic end. The central battle section is impressive, as is the ensuing funeral procession. Karabits's energy prevents the work from sprawling, and again, the playing is superb.

Esbe: Desert Songs (Music and Media)

Esbe: Desert Songs (Music and Media)

Desert Songs grew from classically trained guitarist esbe’s fascination with Middle Eastern literature, prompted by a discovery that European troubadours had been inspired by travelling Bedouin poets. A few days spent in the British Museum introduced her to the likes of Ibn Sa’id, Jamil of Udhra and Jalaluddin Rumi. Verses by Rumi, a 13th century Afghan mystic, dominate the disc, the words heard in newly commissioned translations by Raficq Abdullah. As read in the booklet, the texts are strikingly contemporary, tales of love, longing and loss, accompanied variously by an ensemble including guitar, strings and percussion. Esbe sings, occasionally multi-tracked.

It's impossible to know exactly how 13th century music sounded, but the standout tracks here are the simpler, sparer ones. “Take Heed” features just esbe's unaccompanied vocals, imploring us to listen “or your heart be lost in hell,” and “Where You Dwell” unfolds over percussion and zither. Rumi’s words don’t need ornate musical embellishment, and on just a couple of tracks the arrangements become a little too rich: I'd love to hear unplugged, stripped-down versions. Good notes and full texts are provided.

Add comment