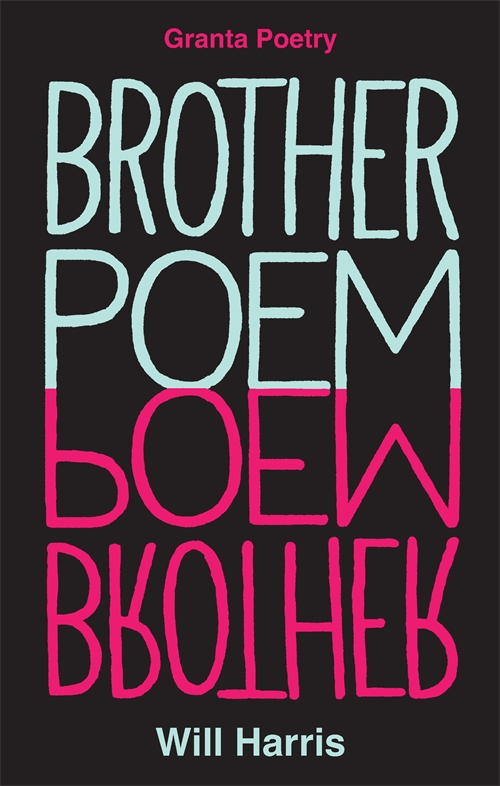

You shouldn’t always judge a book by its cover, but you can get pretty far with an epigraph. The epigraph to Will Harris’s new collection, Brother Poem (following his T. S. Eliot Prize-shortlisted RENDANG in 2020), is a brief but telling prelude, an as-if translated from Russian into English:

There stands the stump; with foreign voices other

willows converse, beneath our, beneath those skies,

and I am hushed, as if I’d lost a brother.

ANNA AKHMATOVA, “Willow” (trans. JENNIFER REESER)

These three lines work both as the book’s framing device and its recurrent textual spectre: like Akhmatova, Harris is concerned with voices, foreignness, dialogue, and the grammar of the hypothetical. More particularly, Harris is writing poems, in the epigraph’s words, “as if [he]’d lost a brother”. This is the main conceit of Brother Poem, to address a fictional sibling and describe a childhood the poet never had. It is a strange idea, but not without precedent: Laura Marling, for example, wrote an album to an at-the-time non-existent daughter, and J. H. Prynne once essayed his idea for what he calls the poet’s “imaginary”, a fantasy speaking partner with whom the poet composes, akin to an imaginary friend.

The book is constructed as a sort of wayward triptych, with the eponymous “Brother Poem” forming the central piece. On either side are poems about commuting, cuttlefish, the etymology of the word “banal”, and recording voice-notes on your phone. Despite the topical range, the book is threaded intricately together by a sustained fascination with what could have been, whether that’s an unreal childhood (“You saw me play Final Fantasy VI”), our time misspent or spent doing almost nothing (“It was in the garlic | chopped together, talking casually”), or the drafts, scraps, and false-starts of poems that get left behind (“Every poem is another | poem that didn’t make it”). All the negative labour of a life finds a home in the pages of Brother Poem.

The fake-brother-device – open, surely, to accusations of “gimmick!” – is, in fact, a refreshing fantasy. That is, it makes a nice change to read a book of poems that is not composed of documentary pieces about the poet’s life, in which biography talks over technique; these are not the facts of experience wrought – often with an unacknowledged ethical doubtfulness – into verse. As “Commute Songs” has it, “Always the voice off-screen butts in”. The poems’ relation to us is always sidelong, askew, and generatively awkward. They are poems from an alternate universe, in our world but not of it.

And this does funny things to pronouns:

What will I do

in the future

Use I or him

When I mean you

There is a sort of swirling orbit of pronominal apparitions, each one unclearly defined and ghosting into the next. Elsewhere Harris writes that “A noun is an imperfect substitute for a pronoun”. Imperfect, perhaps, because the noun is too certain about things, whereas the pronoun, in its hazy categorisations, speaks more truly of what a person is – which is very hard to say. As the exemplary poem “Voice Notes” has it,

Even if it could be named it would only be

as some token, some part-for-whole, of what

could be expressed.

Perhaps the poem’s most important centre, rather than the well-worn lyric “I”, is what Harris means when he writes “When I mean you”. In a poem, “you” always has plurality hidden within it, and resists accurate identification. In this case, “you” comes to encompass not only Harris’s possible brother, but also the possible reader, where both ideas function as indeterminate textual imaginings, at once somehow intimate and inexact: the faux-fraternity, a method of near-literal impersonality, creates a strangely touching void that anyone – and everyone – might enter.  This is not to say that these words are not, in some obscure way, connected to the Will Harris that exists. As he’s previously written, “The imagination, so far from being opposed to identity, is the sum of our experiences, recollected and rendered in legible form – it is identity.” There are references to contemporary political events and concerns – to Brexit Day, Capitol Hill, immigration, nationality, and family history (among other things). Identity, in its complex recalcitrance and prismatic refractions, is vital to Harris’s poetic imagination, and is therefore always part of his poetic thinking; but, in Brother Poem, he is able to affirm his particular presence through acts of negation, of uncanny counterfactual, of fraught subjunctive hopes: “I never asked you what | it meant, only what wish it expressed.” These poems are untrue in that meaningful way that only poems can be.

This is not to say that these words are not, in some obscure way, connected to the Will Harris that exists. As he’s previously written, “The imagination, so far from being opposed to identity, is the sum of our experiences, recollected and rendered in legible form – it is identity.” There are references to contemporary political events and concerns – to Brexit Day, Capitol Hill, immigration, nationality, and family history (among other things). Identity, in its complex recalcitrance and prismatic refractions, is vital to Harris’s poetic imagination, and is therefore always part of his poetic thinking; but, in Brother Poem, he is able to affirm his particular presence through acts of negation, of uncanny counterfactual, of fraught subjunctive hopes: “I never asked you what | it meant, only what wish it expressed.” These poems are untrue in that meaningful way that only poems can be.

This is to say that Brother Poem’s central conceit is a risky move, but one that pays off. Indeed, it is even the case that the book is powered by risks of various kinds. Take, alongside those doubtful pronouns above, its formal incoherence: never are two poems the same; the typographical experimentation can occasionally take on the aspect of a cheap magic trick (the ink of one poem, for instance, fades away progressively with each stanza); recognisable features like end-rhyme are rarely, if ever, used; parataxis flirts with non-sequitur; there are pictures.

But the effect, seemingly scattergun, is saved – again – by its conceptual framework. It is as though the texts are so many improvised, transitional objects – like a child at play, imagining endless possible states of being for an unassuming cardboard box. Words, lines, and stanzas work as though passed between distractible kid brothers, before being as quickly cast aside again. In this way they are reminiscent of Frank O’Hara’s I do this I do that poems, in which form is a mode of transient buoyancy, constructed only to serve a moment’s purpose. For Harris too, these poems are objects of wanton restlessness, and are justified in their miscellaneous aspect by sheer imaginative versatility.

And Brother Poem is well aware of its own riskiness, and the fact that it may have gone too far. It is gilded with guilt and littered with doubtfulness about its own purpose, constantly anticipating its own possible failings: “But I don’t know what I’m doing, or know just enough – scraps of poems, conversations, family stories – to make it work briefly, though I always speak so badly. I hate talking out loud”. The confession is its saving-grace. Harris, through his generous imagination, gives us “just enough”; his words work for and in the moment, however brief that may be; his worlds are held in the most tentative modality: they exist for as long as we read.

- Brother Poem by Will Harris (Granta Poetry, £10.99)

Add comment