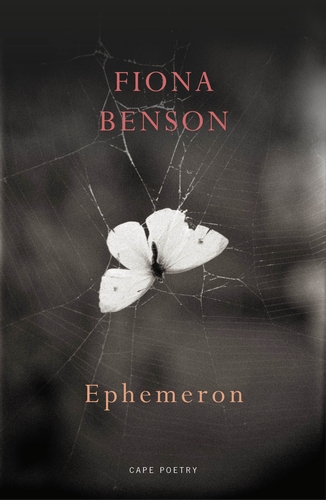

Fiona Benson’s new collection of poems, Ephemeron (Jonathan Cape, 2022), tries to capture those things that are always moving out of grasp. It does this through four sections: the first, “Insect Love Songs”, thrums with a lyric transience, zeroing-in on the minute and fleeting world of bugs, from mosquito to mayfly; “Boarding-School Tales” utters the difficult facts of childhood with sensitive recollection; in “Translations from Pasiphaë”, she retells the Minotaur myth, giving voice to Asterius’s mother and displaying the fraught, familial heart of the labyrinth; and the concluding section, “Daughter Mother”, describes the fearful love of motherhood, attending to the present and dreaming of the future: “My girls, you were pilot lights to me. | In the worst storms, how you shone.”

Ephemeron was shortlisted for this year’s TS Eliot Prize. I had the pleasure of discussing the book with Fiona on the cusp of the winner’s announcement. She gave me her thoughts on prizes, poetic subject and practice, and the dangers of perfectionism.

Jack Barron: Your new book, Ephemeron, was shortlisted for the TS Eliot Prize, as were both of your previous books. What do prizes do for poetry?

Fiona Benson: In a sort of selfish way, I’m really grateful to be shortlisted, because there isn’t that much space for poetry at the moment. Newspapers are cutting down coverage, and it’s difficult to get books out there. The people behind the prizes put in so much work, and show that people care. I’m very grateful for that. At the same time, I think that every book is special, and different, and teaches you ways to read. The idea of choosing between the books on this year’s shortlist, for example, is very difficult, because each work should be loved.

JB: Ephemeron has four sections: “Insect Love Songs”, “Boarding-School Tales”, “Translations from Pasiphaë”, and “Daughter Mother”. Would you be able to tell me a little about its composition?

FB: The first section – “Insect Love Songs” – was probably the most deliberate. I applied for a commission on the theme of “urgency”, and wanted to write about insects because I’ve always had an interest in the natural world. I read somewhere that people can be suspicious of commissioned poems, but you just have to trust that you will feed your subconscious and a poem will come out – and I think it did. It became about human interaction with insects and how callous that can be – pouring water down an ants’ nest, for example.

The other section that came together very cohesively was “Translations from Pasiphaë”. I hadn’t intended to write about myth again, but I occasionally teach in Crete and did a myths-of-Crete-based course, and, during that, one of the “Pasiphaë” poems came through very strongly. I was hooked because the story of the labyrinth has always really disturbed me, and Pasiphaë (the Minotaur’s mother) is a fascinating figure. So, that all came in a nice, big, obsessive rush.

Regarding the other two sections: there’s one about boarding-school and one about being a mother and a daughter. I think in some way they’re linked. My daughter’s about the age that my sister and I were when we were sent to boarding-school. There’s a kind of bridge in my head between those sections.

JB: Each section is, in different ways, dealing with evasive or transient subjects, be they childhood memories or the lives of insects. Why write a poem, for example, called “Mayfly (Ephemera danica)”?

FB: I wanted to give that poem the flickeriness of the mayfly, and present a fragmentary but fluent thought. Of course, once hatched they have very little time to mate and lay their eggs before they die, but the speed is just a question of perspective. All of our lives are the same; we’re just dealing in different time-scales: in terms of deep time, humans are just skittering around on the surface of things. Each life is as urgent as the next.

JB: That poem, although it’s relatively brief, has a density of sound, which gives it a kind of surprising durability.

FB: I like the idea that poems can be durable because of the sounds they make. It’s a way they can become memorable – when sound works with meaning.

JB: Are there any particular writers who informed “Insect Love Songs” and your thinking about ephemerality?

FB: There are so many! I find Anne Carson continually inspiring. In terms of insects and the eco-poetry tradition, I love Gerard Manley Hopkins and Seamus Heaney, and more recently people like Alice Oswald. There’s a really strong tradition of eco-poetry, in terms of both fauna and landscape, and it’s currently manifesting a variety of interesting ways.

JB: There seems to be – in “Insect Love Songs” but also running right the way through the book – a kind of anxiety about what one chooses as a poetic subject. For example, in the poem “Blue Morpho” you write about “trying to force a poem | from this butterfly’s blue-sheen, which I pretend I’ve bought to study”.

FB: There is this anxiety about not being exploitative. You want to be sensitive to the material. For the project that informed “Insect Love Songs”, I was doing poetry workshops as well, so I was bringing in specimens of dead bugs – which, as a lifelong vegetarian, felt quite wrong! The Blue Morpho is so beautiful, and there’s a whole industry whereby it’s bred and sold and used as art. As humans, we’re naturally pulled towards that amazing colour. There’s something very primal about it. As a child I remember buying a butterfly on a school trip – you used to be able to buy them in boxes – and my mother flipped out. I hadn’t realized that it had been bred for this purpose; I thought it had been picked up off the forest floor. I think I’ve always had a guilt about that little butterfly, so I wrote about our tendency to desire animals as property.

JB: This guilt travels into “Daughter Mother”, and a poem called “Dispatches”, in which you imagine your daughters growing old, getting Alzheimer’s, and living in a nursing home. This must have been a difficult thing to imagine.

FB: I do write about fears for my children, and there’s a further fear that somehow this might cause something bad to happen. But I remember speaking to John Burnside years ago, and he said that sometimes naming the fear is a protection in itself. I think that’s what I’m doing. My grandfather had Alzheimer’s, which was very frightening, and after graduating I went to work in a nursing home in case other members of my family became unwell. These are each means of protection.

JB: Are you a confessional poet?

FB: I don’t mind being called a confessional poet. I know there’s a kind of worry about being called that, because it sounds like you’ve sinned. But the group of poets it puts you in with is amazing: Sharon Olds, Sylvia Plath, and Lucille Clifton, for example. They all write in the confessional genre and, like them, I’m often using real things in my poems, and I think that’s OK.

JB: How do you find a poetic form for these real things?

FB: I let it emerge: I listen to the poem and see what it wants to do. A line will usually appear, or a rhythm will take you, and I think of this as the pulse or heartbeat of the poem.

JB: In the middle of the book, a sequence of poems emerges about your time at boarding-school. They feel like perhaps the most private – and confessional – poems in the book.

FB: Yes, there’s one about an erotic encounter with another girl, and it’s very private. But I make myself read it quite a lot – because, essentially, I really don’t want to read it. But because coming out was such a huge ordeal – certainly for my generation – I feel it’s very important to read this poem as an act of solidarity.

JB: You dedicate “Boarding-School Tales” to a psychotherapist-poet?

FB: Yes, my friend Hélène Demetriades. It’s not that these poems are psychotherapeutic, but I was working with Hélène on her first book of poems, and she went to boarding-school too. She was extremely supportive of owning that experience, because there’s a kind of double-bind for people who have been to boarding-school. One the one hand, you’ve had this privileged education, but at the same time you were sent away from home at a very young age. I was bullied by both adults and children. It was very traumatic. There’s a privacy to this experience, but it’s a kind of collective privacy, suffered by many children at these kinds of school. Hélène was very good at saying that it was alright to write about this. Girlhood is a very storied place. I’m interested in story-telling.

JB: Ephemeron ranges from songs to tales to translations, covering a lot of formal ground. How do you think its sections hang together?

FB: I think there’s a new pressure for poets to make a book hang together thematically. I tend to write in albums, and I just hope they speak to each other. But the most important thing for me is to keep writing, and at a certain point you have to clear your desk and move on to the next thing. Perfectionism is the enemy of creativity, as my friend Sophie Herxheimer would say.

JB: So do you have a drafting process that produces a lot of excess material?

FB: Yes. The “Pasiphaë” sequence, for instance, was originally double the length.

JB: Where does the excess go?

FB: It just goes. I have drawers full of notebooks that I need to burn some day. I have a notebook where the primary stuff goes, and then I have drafting books. But I don’t archive them and, in the end, they’re for the fire.

- Ephemeron by Fiona Benson (Jonathan Cape, £12.00)

- Book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment