Janet Malcolm: Still Pictures - On Photography and Memory review - a rare glimpse at a guarded personal history | reviews, news & interviews

Janet Malcolm: Still Pictures - On Photography and Memory review - a rare glimpse at a guarded personal history

Janet Malcolm: Still Pictures - On Photography and Memory review - a rare glimpse at a guarded personal history

Old photographs catalyse this evasive and poignant book of memoirs

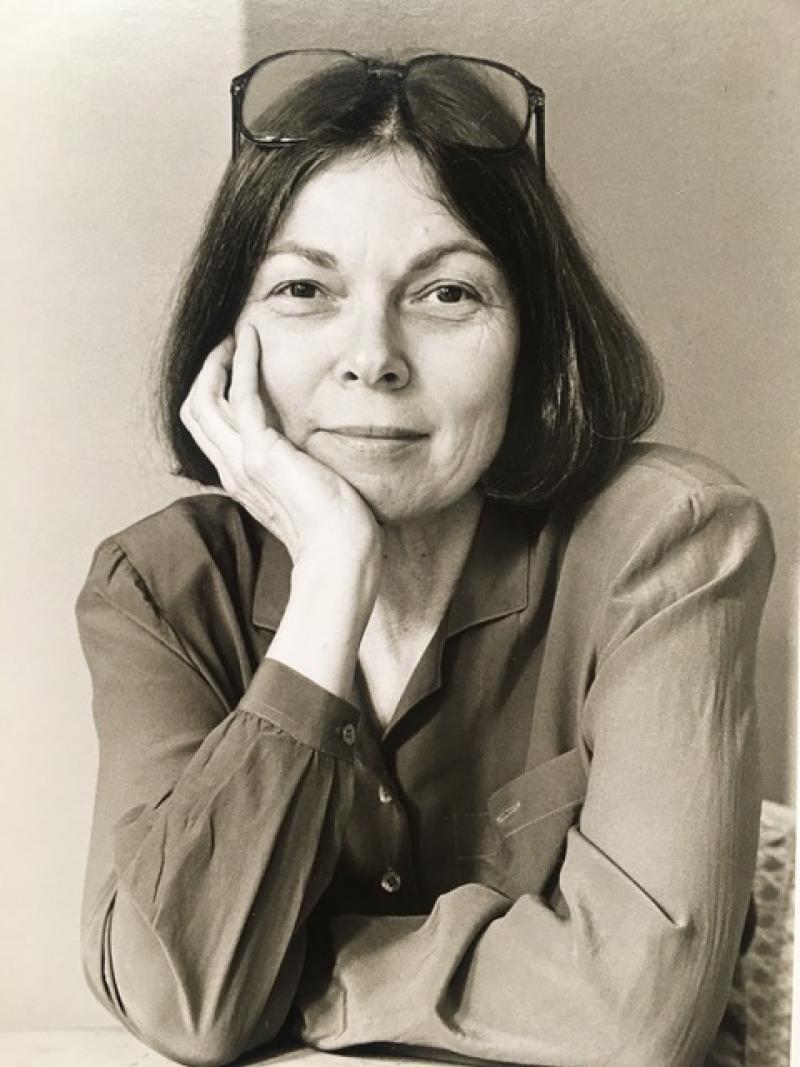

For almost half a century, from the mid-1960s until her death in 2021, Janet Malcolm was a staff writer on the New Yorker where her meticulous reporting and provocatively strong opinions won a devoted readership. Yet she began her career as a kind of hack, writing magazine fillers about shopping and design.

No doubt these routine weekly assignments, and later a photography column, helped her to develop the keen eye for detail that she brought to long-form journalism. In countless articles and a dozen genre-bending non-fiction books, including In the Freud Archives (1984), The Journalist and the Murderer (1990) and The Silent Woman (1994), she delved into the world of cranks and obsessives, uncovering stories of bad blood and hidden motives.

Her unsparing investigative style, which often read like detective fiction, illuminated her subjects' lives and pretensions while also questioning her own cranky profession. Reporters were the literary equivalent of burglars and con artists, she argued, pilfering material and betraying trust. In particular, the opening sentence of The Journalist and the Murderer provoked a chorus of disapproval: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible.”

Much of her work focused on people's vanity and self-regard. Yet she herself was too modest or detached to explore what happens when the reporting eye – and "I" – becomes the subject of its own gaze. In Reading Chekhov (2001), she diagnosed the Russian writer's "autobiographobia" – and it was a condition that Malcolm shared. She too was more comfortable probing the lives of others than her own. The lens of her sensibility always faced outward, not inward, for reasons she cited in a brief essay, “Thoughts on Autobiography from an Abandoned Autobiography”: “Memory is not a journalist’s tool. Memory glimmers and hints, but shows nothing sharply or clearly. Memory does not narrate or render character. Memory has no regard for the reader.” She was not an obvious memoirist, in other words.

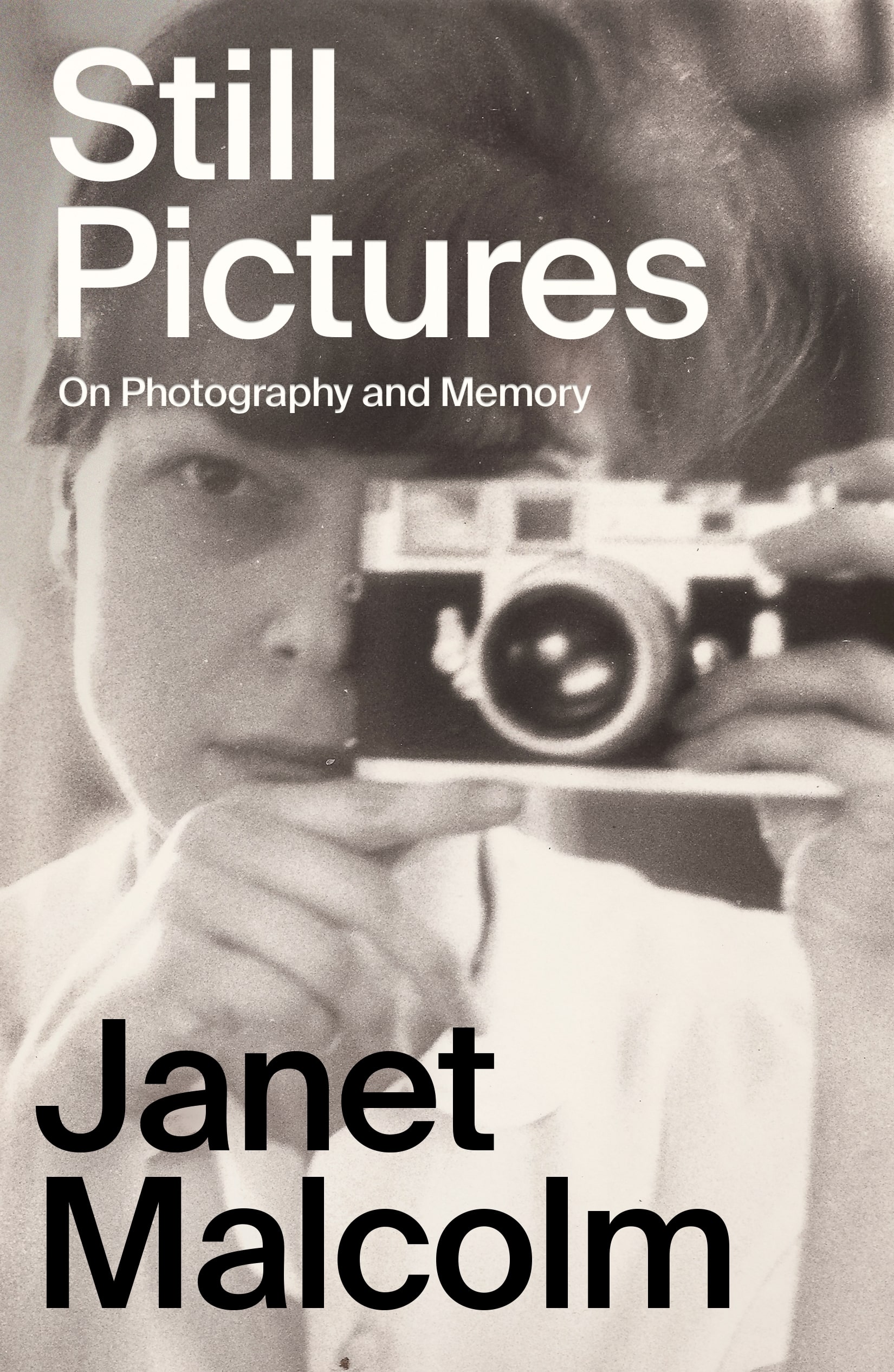

How delightful then to discover this posthumous book of memoirs, even if, typically, Malcolm finds a way to deflect the reader's attention from herself. So, rather than a chronological narrative, Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory offers 26 vignettes prompted by snapshots she found at home, shortly before her death, in a box labelled “Old Not Good Photos”. Most of the chapters begin with a small black-and-white photo, or with family letters and diaries, dating back to pre-war Czechoslovakia where Malcolm, née Jana Wienrova, was born in Prague in 1934 to a non-observant Jewish family.

The most heart-wrenching image is of her, aged five, leaning out of a train window with her parents en route to Hamburg to board a ship for America. Having bribed Nazi officials for an exit visa, they were “among the small number of Jews who escaped the fate of the rest by sheer dumb luck”. Other chapters paint a picture of émigré life in post-war New York, though Malcolm also touches on the $10-million libel lawsuit brought by Jeffery Moussaieff Masson, the anti-hero of In the Freud Archives, who claimed that Malcolm had misquoted him. The case dragged on for a decade until the US court of appeals ruled in the New Yorker's favour. Another chapter describes an equally long-running but romantic affair with Gardner Botsford, her editor at the New Yorker, whom she later married.

The most heart-wrenching image is of her, aged five, leaning out of a train window with her parents en route to Hamburg to board a ship for America. Having bribed Nazi officials for an exit visa, they were “among the small number of Jews who escaped the fate of the rest by sheer dumb luck”. Other chapters paint a picture of émigré life in post-war New York, though Malcolm also touches on the $10-million libel lawsuit brought by Jeffery Moussaieff Masson, the anti-hero of In the Freud Archives, who claimed that Malcolm had misquoted him. The case dragged on for a decade until the US court of appeals ruled in the New Yorker's favour. Another chapter describes an equally long-running but romantic affair with Gardner Botsford, her editor at the New Yorker, whom she later married.

Unlike her Diana & Nikon (1980), which collected many of the pieces Malcolm had written as the magazine's photography critic, Still Pictures is not a book about aesthetics or even about photography itself. Indeed she admits that few of the grainy images have any artistic merit. In the final chapter, "A Work of Art", she discusses a particular picture because it was nothing of the kind, a snapshot of an unknown couple on a tennis court that Botsford kept on his desk for many years because it was so bad it was almost avant-garde. The opening chapter, “Roses and Peonies”, had taken a genuine work of art – an Ingres oil portrait of a man in his sixties, hand on thigh – and juxtaposed it with a photo of herself as an infant sitting on a doorstep, adopting the same pose.

Her real subject is the way snapshots can trigger memories, some of which are "barely readable", like old photographs, full of gaps or beyond recognition. However, as Malcolm notes, "occasionally, like memory itself, one of these inert pictures will suddenly stir and come to life.” The gaps are important, she argues, because most of what happens to us goes unremembered. "The events of our lives are like photographic negatives," she adds. "The few that make it into the developing solution and become photographs are what we call memories.” In Still Pictures, Janet Malcolm has taken all three elements – pictures, memories and gaps – and arranged them into a mischievous verbal collage.

- Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory by Janet Malcolm (Granta, £14.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Add comment