Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism | reviews, news & interviews

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

Richard Dorment: Warhol After Warhol review - beyond criticism

A venerable art critic reflects on the darkest hearts of our aesthetic market

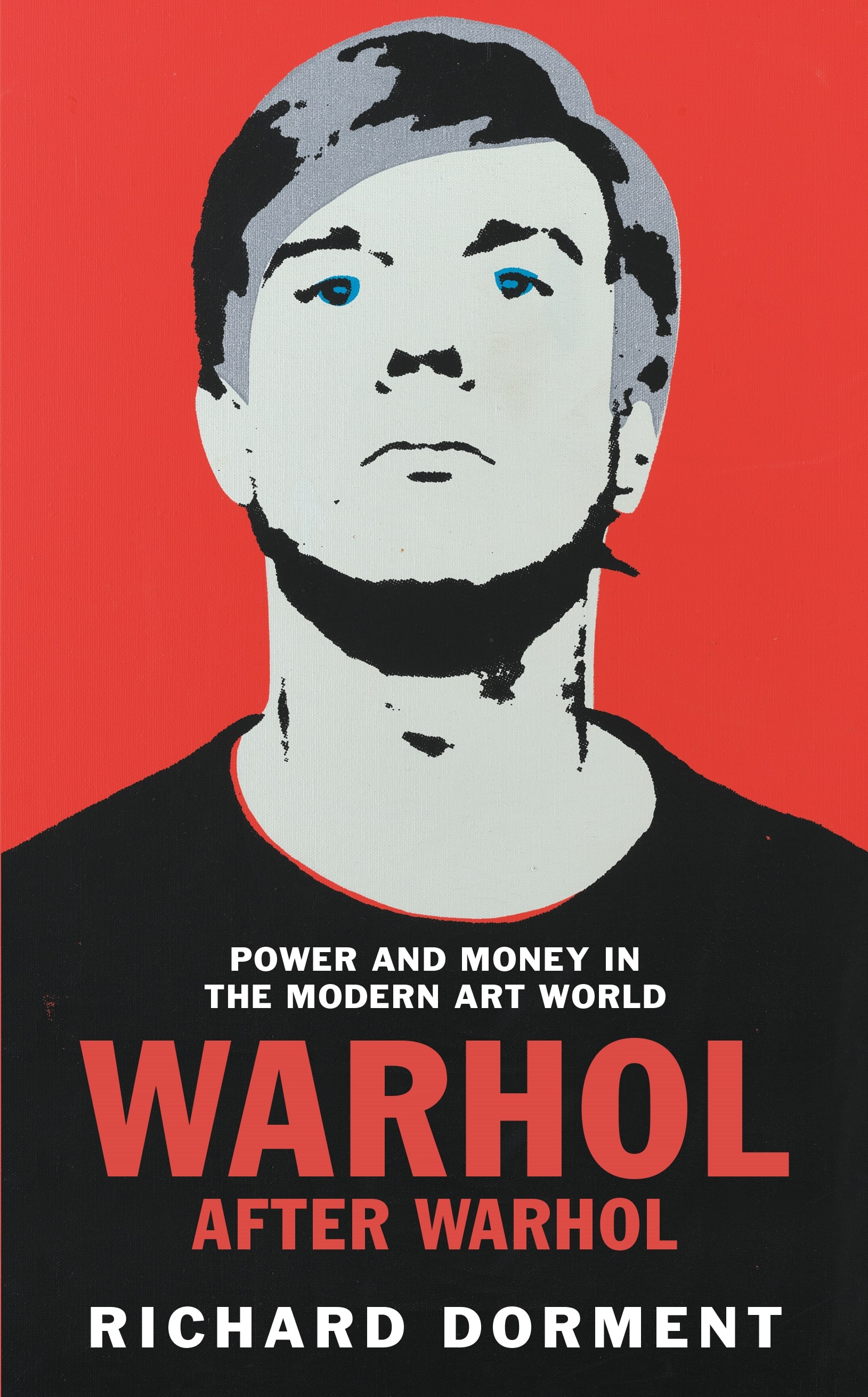

2023 was a good year for Andy Warhol post-mortems: after Nicole Flattery’s Nothing Special, after Alexandra Auder’s Don’t Call Home, Richard Dorment’s Warhol After Warhol.

Their publication journeys undoubtedly benefitted from the value Anglophone cultural programming currently puts upon "pre-awareness": bookshops, for instance, are full of feminist and queer retellings of well-known novels and myths; the highest-grossing film of last year was Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, the first of many films that the toy company Mattel intends to eke out of its intellectual property.

For Warhol scholars, it is much the same as it ever was. Rarely does a year go by without a new exhibition or biography, or an interview given by someone with whom Warhol was tangentially associated. With the possible exception of Pablo Picasso, it is difficult to name an artist with a life so anecdotally rich, so already like an expanded universe or media franchise. This is incidental to Warhol's practice: he was a prolific, documentary artist who habitually displaced the tasks of art-marking onto others. (Flattery’s novel makes both tendencies explicit: its narrator is one of the typists of Warhol’s A, a novel – a work of conversational transcription where every typing error and abbreviation is reproduced verbatim.) "The story of Andy Warhol", as Wayne Koestenbaum once put it, "is the story of his friends, surrogates and associates."

Established shortly after the artist’s death in 1987, the first task of the Andy Warhol Foundation was to find a way to deal with such unwieldiness, to capitalise upon the size and increasing value of his oeuvre and his considerable personal art collection and property portfolio. At the time of his death, it was reported that "4,118 paintings, 5,103 drawings, 19,086 prints and 66,512 photographs" made by Warhol were in his possession.

Established shortly after the artist’s death in 1987, the first task of the Andy Warhol Foundation was to find a way to deal with such unwieldiness, to capitalise upon the size and increasing value of his oeuvre and his considerable personal art collection and property portfolio. At the time of his death, it was reported that "4,118 paintings, 5,103 drawings, 19,086 prints and 66,512 photographs" made by Warhol were in his possession.

It is out of the Foundation that the Andy Warhol Authentication Board was established, and it is this latter institution that Warhol After Warhol is chiefly concerned. While a catalogue raisonné had already been compiled by the German art historian Rainer Crone in 1970, Warhol’s death made possible the existence of an absolutely definitive list of his works: the Authentication Board was established to verify its contents. Funding such a document, the Foundation would (by its own private admission) "contribute to the stabilisation of the market for Warhol works over time, [benefitting its] long-term goal of converting its Warhol works into cash for favourable prices."

Dorment’s personal involvement with the Board began eight years later: then-chief art critic for The Daily Telegraph, he received a phone call from the American film producer Joe Simon. Centre stage in their subsequent conversation was a silkscreen canvas from a series known as Red Self-Portraits (1965), made with the same acetates used in Warhol’s famous 1964 work, Self Portrait. (Also in Simon’s collection was a work subsequently proved a genuine piece of apocrypha: "a meticulous arrangement of crisp one-dollar bills pasted onto a small canvas.") Wishing to sell the works, Simon was advised to submit them to the Board for approval. Works owned by the Foundation were exempt from such a process; anyone else displaying or selling a Warhol without its prior authentication would "[receive] a lawyer’s letter stating that the sale could not proceed until the Board confirmed that the artwork was genuine."

The Board rejected both works, stamping their reverse sides with the word denied in indelible red ink – and therefore reducing their sale values to zero.

What followed was an almost decade-long attempt to understand why and how the Board made its decision. Initially met with non-compliance, Dorment’s public criticism of the Board in the pages of the New York Review of Books prompted threats and smears. Comprising the latter two thirds of the book is a legal trial roughly contemporaneous with Dorment’s own interventions: at great personal cost, Simon attempted to sue the Board. His legal team compiled 157 allegations, including:

"worldwide conspiracy to monopolise trade in Warhol’s work in violation of the Sherman anti-trust laws, and conspiracy to persuade Warhol owners to submit their works for authentication when denial was a foregone conclusion."

A dead Russian oligarch, possible phone-tapping, a mysteriously useless prosecution team: Warhol After Warhol aspires to the tone and pace of a legal thriller; Dorment’s actual argument for the Red Self Portrait’s authenticity instead resembles a piece of detective fiction; he must show the means, motive and opportunity of its production. Warhol’s displaced approach to art making here comes in useful; so too, his documentary ethic: Dorment has a great deal of evidence to draw upon, both contemporaneous and retrospectively given. The Red Self Portraits, we learn, were made by the trade magazine mogul Richard Ekstract: Ekstract had lent Warhol expensive video recording equipment; Warhol negotiated its long-time loan by lending him the acetate transparencies made from the earlier series of self-portraits. He would later select one of the Ekstract-produced portraits for an exhibition at the ICA in Philadelphia. He also chose to sign, date and dedicate another from the series, having "personally chosen the picture for the image on the dust jacket of the [1970] catalogue raisonné".

Members of the now-disbanded Board are still employed to the Foundation, and it is through possible emendations to the newer catalogue raisonné that they continue to influence decisions on Warholian canonicity. As in the example of some screen-printed underwear sold by Christies for $16,250 in 2011, due process does not apply to works sold by the Foundation.

What Warhol would have thought of such an afterlife is unclear: he famously described "good business" as the "best art"; in the final interview he ever gave, he expressed dislike of others’ attribution of his name to works with which he had not personally signed off. And while it is a cliche, it is also difficult to find instances of institutionally successful American art that has not benefitted from dubious financial resources: the philanthropy the Sackler family, for instance, or the CIA’s infiltration of Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s. A subtler example might be the fact that US art collectors benefitted hugely from the fire-sale of European avant-garde art during the 1930s and 1940s, and were incentivised via tax breaks to donate these works to public art galleries.

Given how quick Dorment is to champion the editorial freedoms of the NYRB, how much he wishes for a critical culture in which mistakes in attribution can be "seen, debated, and... corrected", we would do well to remember that reliance upon tax-break seeking donors is still commonplace in non-legacy culture magazines in America. It is striking how much more critically ambitious and better-paying these publications are compared to British equivalents. If the equation that Warhol once made between art and business is a vindication of the future that his Foundation has secured for him, it is also a good description of art’s conditions of possibility. Criticism’s, too.

- Warhol After Warhol: Power and Money in the Modern Art World by Richard Dorment (Picador, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment