Thomas Hardy: Fate, Exclusion and Tragedy, Sky Arts review – too much and not enough | reviews, news & interviews

Thomas Hardy: Fate, Exclusion and Tragedy, Sky Arts review – too much and not enough

Thomas Hardy: Fate, Exclusion and Tragedy, Sky Arts review – too much and not enough

Programme does its best to shine a light on the bleak Wessex writer

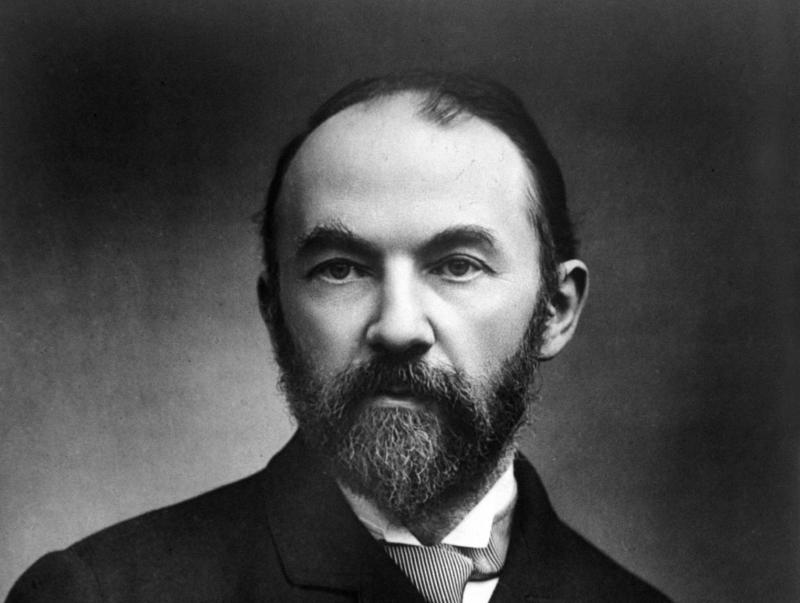

Born in 1840, Thomas Hardy lived a life of in-betweens. Modern yet traditional, the son of a builder who went on to become a famous novelist, he belonged both to Dorset and London. When he died, his ashes were interred at Westminster Abbey, but his heart was buried separately alongside his first wife in the village of Stinsford in Dorset.

In a lifetime that spanned the early Victorian period and the aftermath of the First World War, Hardy witnessed huge changes: the mechanisation of farming, the rapid growth of cities, the transformation of transport and communications. Claire Tomalin repurposes one of his poems to label him the “time-torn man” in her biography (2006). Much of his work is permeated by the seismic ruptures that he experienced, explored via the fictional region of Wessex, which was heavily based on the Dorset where he grew up.

For anyone interested in learning more about Hardy’s life and works, the recent Sky Arts documentary Thomas Hardy: Fate, Exclusion and Tragedy is a good place to start. The programme relies heavily on biographical details and focuses on Hardy’s personal life, particularly his relationships with women, and discusses the difficulties in his marriage to his first wife, Emma, along with his response to her death, and his later marriage to Florence Dugdale, 39 years his junior.

The documentary mostly takes the broad-brush thematic approach that its title implies, combining a narrative voiceover with expert interviews that home in on specific novels and poems. This left me wondering: who was the target audience? Readers like me who are already fans of Hardy’s work are unlikely to learn much new information, while those unfamiliar with his writing will probably struggle to engage. The focus on Hardy’s romantic attachments, for example, leaves many other key elements of his life unexplored; more could have been made of Hardy’s early family life, his relationship with his mother and the fact that his marriage to Emma remained childless.

The opening also surprised me: the documentary begins with a reference to one of Hardy’s lesser-known novels, A Pair of Blue Eyes (1873), generally thought to be the origin of the term “cliff-hanger” (one of the serialised volumes of the book concludes with a character literally hanging off a cliff, with the outcome not revealed until the next instalment). While this is an intriguing piece of trivia, its relationship to the broader themes of Hardy’s life and works that structure the documentary is not fully explored or explained.

It also remained unclear what exactly the documentary was setting out to achieve in its exploration of Hardy’s life in relation to his work, and why now was the moment to do so. Perhaps my feeling of unease stemmed from a concern that this sort of literary documentary is not the best format for exploring a historical writer; it can’t help but mythologise and romanticise its subject.

The documentary’s most visually striking aspect is its exploration of Wessex: a mythical landscape conjured by readings of evocative extracts from Hardy’s novels and poems alongside soaring drone footage of the Dorset coastline and countryside. Interviewee Professor Dinah Birch thoughtfully points out that the wild Wessex landscape – dramatised in novels such as The Return of the Native (1878) – is “one that predates our modern world and which, Hardy suggests, will outlive it”. While these beautiful, sweeping landscape shots may lean towards romanticising the rural landscape, the programme does its best to shine a light on some of the darker aspects of his personality, along with the impact of the Great War on his poetry. If the coming of the railway was a fissure wrought into the landscape at the beginning of Hardy’s life, then the First World War was a rupture that cleft through his later years.

- Thomas Hardy: Fate, Exclusion and Tragedy aired on Sky Arts on 14 September and is available to stream until 14 October

- Read more TV reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Wessex is not a mythical

Wessex is not a mythical region. It is an Anglo-Saxon area of the south of England. We have the Earl of Wessex.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wessex