When did Big Ideas make a comeback at the Turner Prize? Did they ever go away? In its 30-year history it seems that everything that wasn’t painting has been labelled “conceptual art”. But we know that labels can be very misleading, and the “conceptual” in “conceptual art” obviously need not apply.

Walking through the mind-maze of this year’s exhibition of four shortlisted artists, particularly the work of Dublin-born Duncan Campbell, one feels at the mercy of a lot of portentous theorising. But that’s probably because Campbell seems to dominate the exhibition with a film, It for Others, that’s just under an hour long. And though I really want to like Campbell’s work, because it wants to say chewy and interesting things, the chewy and interesting things it wants to say are a bit obvious to anyone who’s thought about them seriously for more than five minutes. What’s more he says them in a way that is both terribly obvious and indigestible. If you actually break it down, it all ends up sounding art-school trite rather than seriously challenging or unsettling.

Campbell’s film takes as its starting point Chris Marker and Alain Resnais’ 1953 film Statues Also Die. This film challenged Western responses to African art, with the title referring to how, under colonialism, this so-called “ethnographic” art had become denuded of its original purpose and context – hence it had become a dead language.

This is just a completely ghastly turn of events – the complete sealing off of the echo chamber

Campbell concurs with an argument made much more directly and eloquently 60 years before his own film, when African nations were still under colonial rule and colonialism hadn’t yet become a dirty word – hence it was properly radical and was censored in France. To this mix, Campbell introduces notions of value, hopping and skipping between wildly disparate-seeming connections (Adam Curtis does this so much better) which take in everything from Chinese textile workers to an IRA "volunteer" – he and Tate marketing are careful not to use the word “terrorist” – whose photographic image in combat has been used on Christmas stockings. Then we’re told of the disconnect between notions of value in art and the actual art object, as if we’ve really never thought about all that, or any of the other stuff, before. So why does Campbell make it all so tiresomely obfuscating? Institutions like Tate are clamouring to embrace this “edgy” stuff. Baffling.

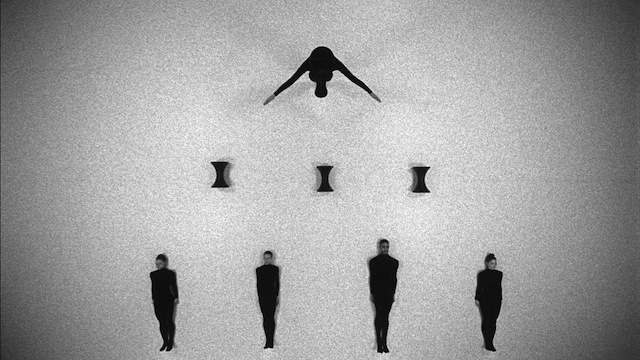

The best bit of the film is the segment showing a beautiful and imaginative piece of choreography by Michael Clark (pictured above: It for Others, 2013). It’s meant to illustrate Adam Smith and David Ricardo’s “Labour Theory of Value”, as laid out by Marx. Whether it will prove helpful to students of economics, I have no idea, but, hell, they should watch it anyway. And at least it adds more "value", as do the segments of Marker and Resnais’ original footage, to Campbell’s somewhat pretentious film.

The best bit of the film is the segment showing a beautiful and imaginative piece of choreography by Michael Clark (pictured above: It for Others, 2013). It’s meant to illustrate Adam Smith and David Ricardo’s “Labour Theory of Value”, as laid out by Marx. Whether it will prove helpful to students of economics, I have no idea, but, hell, they should watch it anyway. And at least it adds more "value", as do the segments of Marker and Resnais’ original footage, to Campbell’s somewhat pretentious film.

James Richards' work is even thinner. In Rosebud he uses photographic images to make a video collage. His theme is eroticism and censorship, and he’s photographed pages from photography books in a Tokyo public library which have been officially censored. This has been done crudely by simply scratching out the offending part of the image: a Man Ray picture with the female genitals scratched out; Robert Mapplethorpe’s bullwhip self-portrait similarly erasing the offending spot. The effect reminds you of Bellocq’s photographs of his Storyville prostitutes with scratched-out faces, but these are neither as captivating or as mysterious, since most photography-lovers will know these undoctored images well. Meanwhile, intercutting the stills from the photography books is grainy black and white footage Richards has filmed: in one recurring sequence a sprig of elderflowers caresses skin, lips, a puckered anus, all in extreme close-up. It’s a sensual world, to quote a Kate Bush song, so get over it.

Richards has a further two pieces in the exhibition, and these are much weaker, including a slide show of photos of cuts, bruises and blooded flesh which you quickly see turns out to be theatrical make-up (pictured above: The Screens, 2013). The other work takes as its subject the Eighties New York street artist Keith Haring, or at least his absence. Six big banners show three of his male lovers and three male gallery dealers, each one a double portrait in which Haring appears, but only partially, since the image has been cropped. If this is what rocks the judges’ world then so be it, but again I'm baffled. This is not good art. It doesn't even come close.

Richards has a further two pieces in the exhibition, and these are much weaker, including a slide show of photos of cuts, bruises and blooded flesh which you quickly see turns out to be theatrical make-up (pictured above: The Screens, 2013). The other work takes as its subject the Eighties New York street artist Keith Haring, or at least his absence. Six big banners show three of his male lovers and three male gallery dealers, each one a double portrait in which Haring appears, but only partially, since the image has been cropped. If this is what rocks the judges’ world then so be it, but again I'm baffled. This is not good art. It doesn't even come close.

Then there’s Ciara Phillips, whose wallpaper of blurry screenprints (main picture) is attractive enough, and naturally, because it's screenprint wallpaper, one thinks of Warhol, but again, seriously? As one part of the installation, there's a cubicle with a speaker placed above head level where you hear words, in alphabetical order, that might provoke "interesting topics of conversation". Do the judges really think this makes the grade? Each judge is a director of an art institution, including the chair of judges, and Tate Britain director, Penelope Curtis – that’s five directors of art institutions – all picking, again and again, from the same galleries (if I see another Showroom gallery artist included in a contemporary Tate show or nominated again for the Turner Prize I'll scream). Curtis must hate journalists as she appears to have banned them from being on the panel. I’m not necessarily suggesting journalists would pick better art – oh, OK, maybe I am – but could the Turner Prize become any more insular and inward-looking than it has this year? This is just a completely ghastly turn of events – the complete sealing off of the echo chamber. What about a little diversity?

Finally, there’s Tris Vonna-Michell, who’s a photographer, filmmaker and performance artist. There are two films of his here, and I’m intrigued by one, a slide presentation that appears to be a fictional story, though it may be half fact, involving the (fictional) narrator’s grandfather, an architect, in a dangerous tale of wartime capture and survival in Berlin (pictured above: Postscript IV (Berlin), 12014). But as soon as I start following the narrative, it fragments (fragmented, non-linear narratives have undoubtedly become a style cliché – a mannered default), though it becomes difficult to sustain interest only for a very practical reason – there’s too much noise bleeding from the adjacent gallery. I would have liked to have spent just a little more time with this work, but Campbell, with his hour-long film, gobbled it up somewhat. That said, this really isn't a vintage year.

Finally, there’s Tris Vonna-Michell, who’s a photographer, filmmaker and performance artist. There are two films of his here, and I’m intrigued by one, a slide presentation that appears to be a fictional story, though it may be half fact, involving the (fictional) narrator’s grandfather, an architect, in a dangerous tale of wartime capture and survival in Berlin (pictured above: Postscript IV (Berlin), 12014). But as soon as I start following the narrative, it fragments (fragmented, non-linear narratives have undoubtedly become a style cliché – a mannered default), though it becomes difficult to sustain interest only for a very practical reason – there’s too much noise bleeding from the adjacent gallery. I would have liked to have spent just a little more time with this work, but Campbell, with his hour-long film, gobbled it up somewhat. That said, this really isn't a vintage year.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment