Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Britain | reviews, news & interviews

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Britain

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Britain

A lacklustre evocation of an exciting, radical period

The exhibition starts promisingly. You can help yourself to an orange from Roelof Louw’s pyramid of golden fruit. Its a reminder that, for the conceptualists, art was a verb not a noun. Focusing on activity rather than outcome, these artists were committed to the creative process rather than the end product. The idea was what mattered, and if it led to an open-ended exploration, so much the better.

For centuries, the whole point of art had been its longevity; now mutability and destruction were welcomed as part of the creative process. Left intact, Louw’s pyramid of oranges (pictured below right) would slowly moulder and decay; if the fruit was removed however, the pyramid would quickly diminish. Either way the sculpture would disappear, leaving nothing but a photographic record and a memory.

St Martin’s School of Art was a hotbed of unruly behaviour. The sculptor Anthony Caro taught there and, inspired by meetings in New York with American critic Clement Greenberg, he preached that art should be about nothing but itself. Pure, undiluted abstraction was the goal; everything else was a distraction.

St Martin’s School of Art was a hotbed of unruly behaviour. The sculptor Anthony Caro taught there and, inspired by meetings in New York with American critic Clement Greenberg, he preached that art should be about nothing but itself. Pure, undiluted abstraction was the goal; everything else was a distraction.

Students like Bruce McLean, Barry Flanagan and Gilbert & George responded to this hermetic and self-referential view by throwing open the doors to embrace the element of time and the messy unpredictability of change. And John Latham, who also taught at the college, encouraged the dissenters. He borrowed Greenberg’s influential book Art and Culture from the college library and, during the summer of 1966, held a party; guests were invited to chew the pages and spit out the remains. Latham then fermented and distilled the pulp into a liquid. When asked to return the book, he gave the library a phial of the liquid and was promptly dismissed from his post.

It was de rigueur to use unorthodox media like photography, film, television and video, installation, performance and text, which had no art historical precedents and could reach large audiences. Richard Long and Hamish Fulton turned walking into an art form, while David Tremlett began travelling, making work on the hoof and sending postcards home to alert people to what he was doing. Putting up posters or sending cards, photos, letters and leaflets through the post were important ways of circumventing the gallery system and engaging directly with an audience.

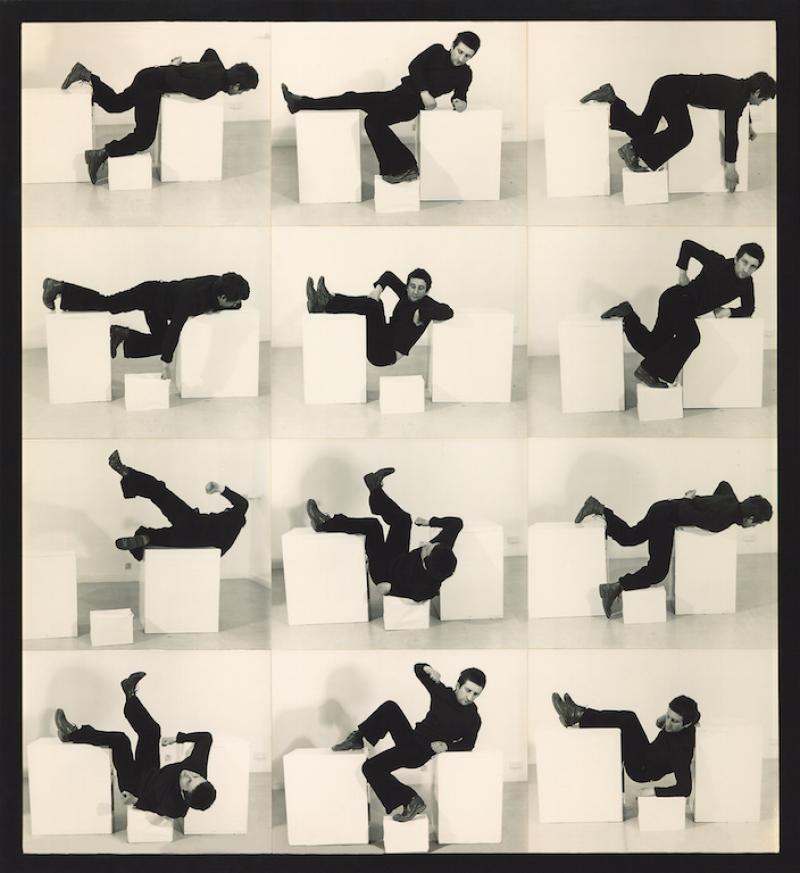

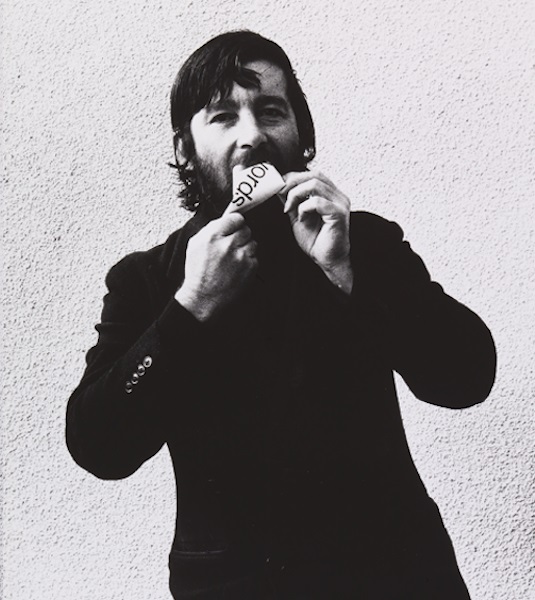

Humour, wit and parody were key elements of the new approach (pictured below left: Keith Arnatt eats his own words in Art as an Act of Retraction, (detail), 1971). John Latham did a one-second drawing and Bruce McLean reclined on plinths in poses mimicking Henry Moore sculptures (main picture). Artists began referring to their output as “pieces”, a concept parodied by Bruce McLean in a booklet from 1972 listing 1,000 ideas. Index Card piece commented on Ed Herring and Victor Burgin’s propensity for archiving and There’ll be a sculpture in the hillside piece referred to sculptures made in remote places by Richard Long.

There is no business like art business piece (sung) satirised Gilbert & George, who had declared themselves living sculptures. They mimed to a recording of the Flanagan and Allen song Underneath the Arches and having done the rounds of the art schools, their table-top performance was taken up by museums and dealers, such as Nigel Greenwood. I remember sitting at their feet as, hands and faces painted bronze in accordance with their new status, they exchanged a rubber glove and a toy walking stick with a tip that squeaked, convinced I was witnessing a key moment in art history.

There is no business like art business piece (sung) satirised Gilbert & George, who had declared themselves living sculptures. They mimed to a recording of the Flanagan and Allen song Underneath the Arches and having done the rounds of the art schools, their table-top performance was taken up by museums and dealers, such as Nigel Greenwood. I remember sitting at their feet as, hands and faces painted bronze in accordance with their new status, they exchanged a rubber glove and a toy walking stick with a tip that squeaked, convinced I was witnessing a key moment in art history.

How, though, to encapsulate in an exhibition such a plethora of unruly ideas, and convey the energy and enthusiasm that fuelled these radical departures? In focusing on work that hangs nicely on the wall or fits neatly into vitrines, Conceptual Art in Britain doesn’t even attempt to convey the scope of these innovations. It favours photographic and written documentation over installation, performance and video and gives an inordinate amount of space to the group Art & Language who treated art as an offshoot of linguistic analysis.

In a play on the word “abstract”, Michael Baldwin silkscreened onto canvas a book review from the Review of Metaphysics. This was the beginning of a period of expropriation in which philosophical texts were reproduced as paintings, published in books and magazines, or hung directly on gallery walls for hapless viewers to plough through. I doubt that anyone read them, since they were incomprehensible to all but a few academics. Soon the group began generating their own material; described as performative writing, it transforms theory into practice. Various forms of analysis – lists, charts, propositions, scores – replace creative action; but the art establishment embraced the group with alacrity and they dominate this exhibition which, as a result, is much drier and more conventional than it need be.

- Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 at Tate Britain until 29 August

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Bogancloch review - every frame a work of art

Living off grid might be the meaning of happiness

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Do Ho Suh: Walk the House, Tate Modern review - memories are made of this

Home sweet home preserved as exquisite replicas

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Ed Atkins, Tate Britain review - hiding behind computer generated doppelgängers

Emotions too raw to explore

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Echoes: Stone Circles, Community and Heritage, Stonehenge Visitor Centre review - young photographers explore ancient resonances

The ancient monument opens its first exhibition of new photography

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Hylozoic/Desires: Salt Cosmologies, Somerset House and The Hedge of Halomancy, Tate Britain review - the power of white powder

A strong message diluted by space and time

Comments

For once Kent is in the right

For once Kent is in the right county. This is exciting, restive, piss-taking, hard-thinking art ill-served by a po-faced, Procrustean show. The exhibitors have not worked out whether the art should look good, fill the space purposefully, or with aesthetic generosity, or just be catalogued in a scrupulous way. There would be nothing wrong with the second--nor in the space given to Art and Language and their arcane disagreements, theology and cod-dramaturgy. But if you're holding a The Fall theme-night, you dig out the rarities; you investigate why Karl Burns left and rejoined; you take an interest in the fashion, the recording technology; you don't just play 'I am Kurious Oranj', then put on something more palatable like Magazine. This art comes from a time when the faultline between various styles of minimalism (formalism, abstract formalism, objectivism, truth-to-materials) and the neo-conceptual was beginning to gape. It was clear then, polemically, and is clear now, philosophically--but with Louw's oranges so prominent somehow it is not clear in the show. In this way the curators forsake responsibility for the experience of the casual gallery-goer without putting anything else in its place. Though mocking, ironically McLean's Henry Moore and Richard Long takedowns are far more formally rigorous than the objects of his satire. I was surprised Sarah Kent did not find space in her piece for Margaret Harrison and Mary Kelly, whose critical and exploratory feminist pieces have becomes perhaps the most sustained and rewarding essays working out of an early 70s conceptual mode.