The lawns, fields, meadows and sheds of the Henry Moore Foundation themselves exemplify the notion of in-and-out, exterior-interior and are thus the ideal setting for exploring the notion of body and void in Moore’s work and the way it is echoed in the sculpture of succeeding generations.

Thus we have a subliminally provocative setting for a succinct, even oddly exquisite (however monumental) selection of the contemporary sculptural avant-garde, varyingly echoing in new guises notions of inside-outside which we can now see obsessively preoccupied Moore. Moore himself, although a teacher for some time at the Royal College of Art where he himself had been a student, seemed to leave no influential legacy, no school. Interestingly, senior sculptors such as Anthony Caro and Phillip King, both of whom actually worked in their early days as assistants to Moore, are not represented.

Yet Moore too had taken sculpture off the plinth, worked in an area between abstraction and figuration, at times a kind of abstract, geometric humanism, and in particular explored dichotomies. There is, as this show has it, body and void, and beyond that, absence and presence.

The Schüttes look as though they could leap up at any moment and cause mayhem; the Moores majestically stay put

There is a handsome and rather provokingly near-invisible high grass North South Line , set in the rough lawn by Richard Long, a new work made for the show, and created on a north-south axis. Its subtlety means it is very easy to walk over, but once noticed it is rather beguiling. The curious lambs in the sheep meadow have rather taken to wandering into and round another new work, this by Richard Deacon, Associate, a playful stainless steel geometric tangle in four interlocking parts. It is an intricate and satisfying riff on Moore’s Locking Piece and Reclining Figure: External Form which are nearby.

Moore’s own work often has a kind of calm which it is easy to mistake for blandness, a neutrality that seems to emasculate emotions. It is a master stroke to site two ferocious, even violent reclining nudes by Thomas Schütte near reclining figures and internal-external forms by Moore – Stahlfrau No 1 and Bronzefrau No 3 both from 2000 are perhaps intended as a millennial comment. Stahlfrau is caught up in some amazing combat, some intensely aggressive situation, contorted either in giving birth or some alarmingly violent self-embrace. In a curious way these overwhelming female figurations, contorted and twisted, yet recognisable, are layered with notions of the classic reclining nude female creatures of western art history, turned into an up-to-the-minute variation reflecting a puzzled and distressed zeitgeist. Their contained savagery underlines the restrained serenity and the fascinating damped-down energy that animate the Moores. The Schüttes look as though they could leap up at any moment and cause mayhem; the Moores majestically stay put.

The anthology does not attempt to suggest legacy or influence but rather, in the show’s own phrase, echoes. Thus Rachel Whiteread’s solid void, Detached 3, a concrete and steel interior of a garden shed, no longer penetrable nor useful, closed forever yet recalling in its unassuming solidity those utilitarian overlooked vernacular sheds which house not only workshops or garden tools, but escapes into solitary endeavour, away from family and housebound domesticity.

There are exuberant large pieces from Tony Cragg, a graceful corkscrew Early Forms St Gallen, 1997 (pictured below), based on the débris – plastic bottles, discarded vessels – that he so elegantly chooses as a basis for his inventive metamorphoses.

The handsomely converted sheds that are the art galleries set in the meadows house a variety of contemporary sculptures, including such convincing masterpieces as Moore’s carved elmwood Reclining Figure. There is the devastating two-part early Damien Hirst, Mother and Child Divided (main picture), a four-vitrine piece of odd poignancy with both calf and cow sliced in two. It is easy to forget how emotionally powerful even affecting these early animalistic pieces of Hirst were, calling on mortality just as they preserved these bodies in formaldehyde, a take on the specimens of natural history.

The handsomely converted sheds that are the art galleries set in the meadows house a variety of contemporary sculptures, including such convincing masterpieces as Moore’s carved elmwood Reclining Figure. There is the devastating two-part early Damien Hirst, Mother and Child Divided (main picture), a four-vitrine piece of odd poignancy with both calf and cow sliced in two. It is easy to forget how emotionally powerful even affecting these early animalistic pieces of Hirst were, calling on mortality just as they preserved these bodies in formaldehyde, a take on the specimens of natural history.

There are miniatures too, and, really surprising, a wryly hilarious joke by that guru, the evangelist of fantasy and happenings and installations, the late Joseph Beuys: Beuys’ Sculpture by Henry Moore is just a twisted rubber band, a convincing reclining figure, perched in a little box inset in a wooden frame. On a much larger scale Sarah Lucas twists pink nylon tights into a convincing take off of Cycladic figures (ancient sculpture which Moore much took to) called Nud Cycladic 6 and sets the resulting sexless humanoid creature onto a breezeblock plinth.

This is not, however, a cosy love-in show. Most of the artists on view are formidably critically successful and innovative sculptors, and hardly any are tainted with the corporate embrace that at times almost smothered Moore in his last decades. It is a highly intelligent compilation with a curious climax, the legacy of criticism incisively expressed either with a light satirical touch or a more profound disillusion.

Simon Starling’s mesmerising 25-minute film, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010, made in a documentary style and with dialogue voiced by Simon McBurney, focuses on an episode when Moore, once a member of the CND, actually made sculpture in celebration of atomic energy. The conceit is a Japanese craftsman preparing Noh masks for a complex mythological play which is, in fact, calling on Enrico Fermi (Moore’s sculpture commemorates the lab in Chicago where Fermi made his discoveries before joining the Manhattan project in Los Alamos), James Bond and Anthony Blunt among others as part of the complex presentation. The scene is set in a nondescript flat with close-ups of the making of masks. The improbable scenario is almost hypnotically captivating and is flavoured by rage at what is seen as the hypocrisy of a public figure misusing his art.

Starling also shows a proposal for a project to sink Moore’s Warrior with Shield in Lake Ontario, encrusted with Russian mussels that had hitchhiked to Canada on Russian cargo ships.

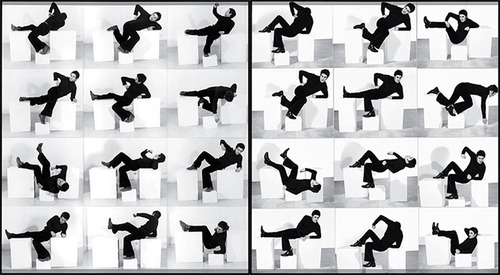

And there is an hilarious coda: photographs of performances by Bruce McLean, Fallen Warrior, 1969 and Pose Work for Plinths, 1971 (pictured above), cheeky carry-ons when Moore was in his international prime. McLean, fully-dressed and male, exuberantly sets himself on a base set in a vast landscape in every convoluted twist into which a reclining figure – in Moore’s case almost invariably female – might be forced.

And there is an hilarious coda: photographs of performances by Bruce McLean, Fallen Warrior, 1969 and Pose Work for Plinths, 1971 (pictured above), cheeky carry-ons when Moore was in his international prime. McLean, fully-dressed and male, exuberantly sets himself on a base set in a vast landscape in every convoluted twist into which a reclining figure – in Moore’s case almost invariably female – might be forced.

Body & Void: Echoes of Moore in Contemporary Sculpture at Henry Moore Foundation, Perry Green, Hertfordshire, until 26 October

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment