Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight | reviews, news & interviews

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Shakespeare’s plays have ever been meat for masher-uppers, from the bowdlerising Victorians to the modern filmed-theatre cycles of Ivo Van Hove. And Sir John Falstaff, as Orson Welles proved in Chimes at Midnight, can be the star of his very own remix, bestriding three plays and dying offstage in a fourth.

Inventive director Robert Icke has now created Player Kings out of the two Henry IV plays for this indelible character. It showcases Falstaff’s relationship with Prince Hal but leaves intact the frame of the play – Hal’s relationship with his father, Henry Bolingbroke, now Henry IV, and the King’s wider patriarchal relationship with the family of tribes in his nation.

With a playing time pushing towards four hours, it’s a little overlong, but the gist of the wonderful originals is intact, despite updating and all the technical tricks modern theatre is heir to. Its success largely comes down to the ball of slow-moving energy at its heart, Sir Ian McKellen, soon to turn 85. I can’t recall an actor who has stayed on top of his game for so long.

This Falstaff's Eastcheap tavern is now a current-day basement bar with exposed brick walls and lounging lowlifes. A man is led in on a leash so coke can be snorted off his back. Its bustling proprietor, Mistress Quickly (a lovely turn from Clare Perkins), is a no-nonsense woman who seems as naturally at home in the 21st century as she was in the 16th. In the midst of the rowdy antics of her establishment, Prince Hal (Toheeb Jimoh, pictured above, right), in leather-look hoodie, jeans and trainers, is a happy participant, helping his mate Poins (Dan Rabin) liberate the funds of a cash drawer with a buzz-saw. Jimoh presents a likeable Hal in the first half, though his delivery can veer too far into shouting at times. Shakespeare’s Hal works best as a calculating young man, Machiavellian almost, who claims he is only playacting being bad so his true worth will make more of an impact when he reveals it; he needs a reflective tone for his memos-to-self, not just a more boisterous style for his stints as a trainee hoodlum.

In the midst of the rowdy antics of her establishment, Prince Hal (Toheeb Jimoh, pictured above, right), in leather-look hoodie, jeans and trainers, is a happy participant, helping his mate Poins (Dan Rabin) liberate the funds of a cash drawer with a buzz-saw. Jimoh presents a likeable Hal in the first half, though his delivery can veer too far into shouting at times. Shakespeare’s Hal works best as a calculating young man, Machiavellian almost, who claims he is only playacting being bad so his true worth will make more of an impact when he reveals it; he needs a reflective tone for his memos-to-self, not just a more boisterous style for his stints as a trainee hoodlum.

Player-kings abound in the text, from uneasy, ailing Henry IV, making a show of strength when he simply wants to absolve himself on a pilgrimage, to Falstaff, lord of misrule. The scene where he and Hal playact being Henry IV and son, donning a cushion as a crown, then swap roles, is a genuine hoot, as are all the comic scenes. (Some of the audience found laughs in the very fact that Henry’s wayward son is called “Prince Harry”.)

McKellen’s timing is pinpoint-perfect, his voice still an impressive instrument that can caress a line or bark it out, his smile unctuously sweet (especially when Falstaff is making ads for his beloved sack). He makes a virtue of his cumbersome fat-suit to present a beached walrus of a man, snuffling through his beard into a hankie but sharp as a tack when mischief is afoot. And he rises to the heart of the play – in his “What is honour?” speech at the Battle of Shrewsbury – projecting genuine disdain, though he will discover the sharp pain of dishonour in the final moments of his relationship with Hal.

There McKellen achieves an extraordinary slow crumple, as if doing a tai chi move, but with his back to us, so that by the time he turns round again to bamboozle Justice Swallow (played as a suitably peppery old goat by Robin Soans), he has regained some of his composure and all of his gift of the gab. The hurt is palpable, though, in one of the saddest scenes in Shakespeare.

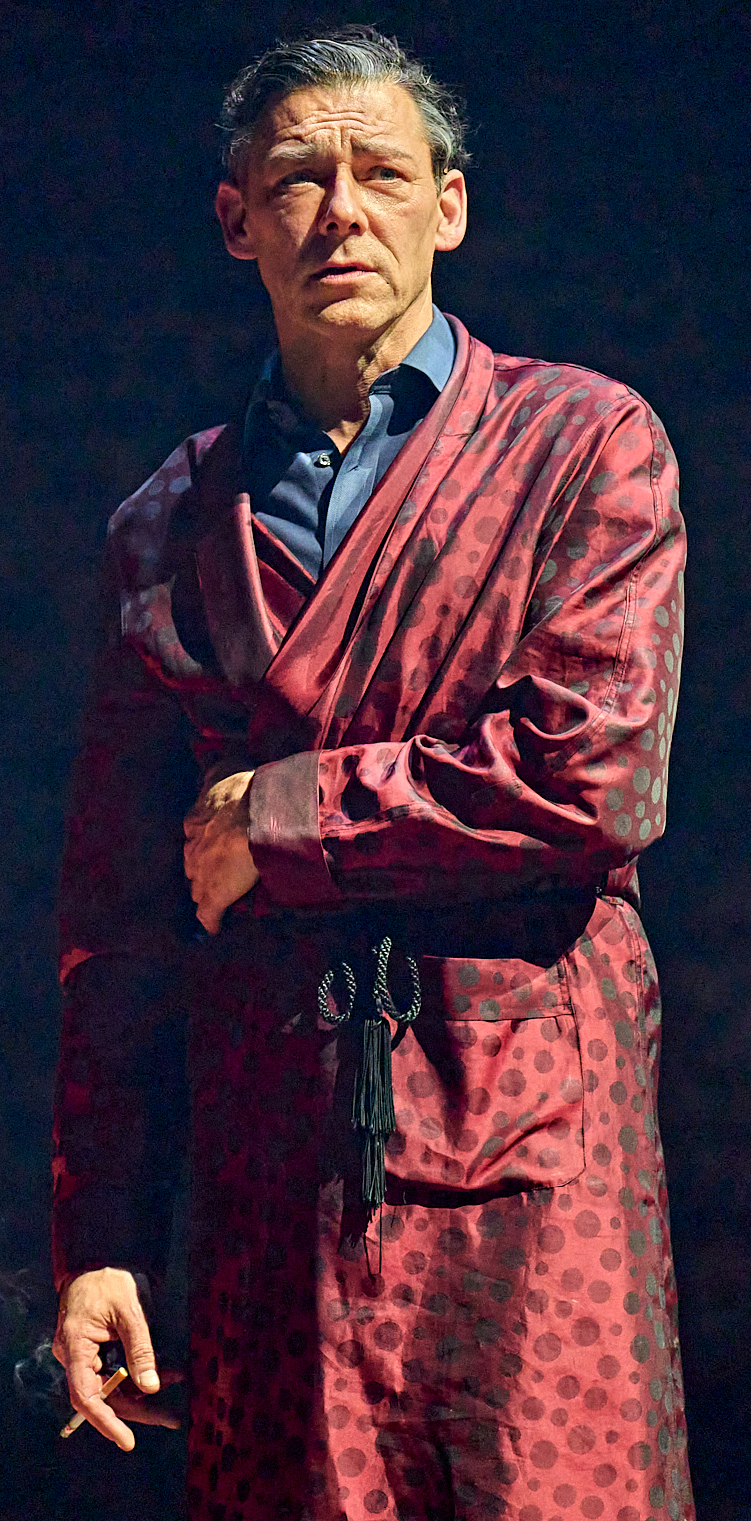

Jimoh commendably lets his mask slip here ever so slightly, so that the regret in his new coldness towards the “old man” can be felt. Similarly, he allows his buried love for his disliked father (Richard Coyle, pictured left) to surface at Henry’s deathbed. He’s the heir apparent, but the son without obvious saving graces, unlike his dutiful brothers, who have rescued the kingdom from the assorted rebel factions that, like querulous children, have taken their sulks with Henry to the battlefield.

Jimoh commendably lets his mask slip here ever so slightly, so that the regret in his new coldness towards the “old man” can be felt. Similarly, he allows his buried love for his disliked father (Richard Coyle, pictured left) to surface at Henry’s deathbed. He’s the heir apparent, but the son without obvious saving graces, unlike his dutiful brothers, who have rescued the kingdom from the assorted rebel factions that, like querulous children, have taken their sulks with Henry to the battlefield.

This wider frame – the machinations in Northumberland, led by the Earl and his son – is totally necessary to round out the portrait of patriarchal relationships that the Henry IV plays present. But compared to the Eastcheap antics these scenes (barring the violent battlefield ones) are inevitably static, with the usual revolving door of nobles and advisors. Coyle, presented as the spit of George VI, cigarette in hand, is a poignant figure, tormented by his part in the death of Richard II, though still capable of rising to the demands of kingship, even asserting his paternal power in fisticuffs with Hal in his dying moments.

The losers in Icke’s mashup are the Hotspurs (Samuel Edward-Cook and Tafline Steen), whose marriage is not the screwballish to and fro many a conventional production presents. And the fatal withdrawal of support by Northumberland that dooms Hotspur, his much lauded son, admired even by Henry IV, is still in the script but passes in a flash. Yet the frame works, a nicely symmetrical one that begins with Bolingbroke accepting the crown, and ends with his son doing the same, a look of panic on his face.

Yes, it’s a long evening (with a sensible 6.30pm start; more please), but it rarely drags. Scene changes are done with ranks of curtains swiftly pulled across, then back again, while surtitles announce key shifts of location. Icke even cheekily splices two scenes together by having the Northumberland rebels take a conference call from the king and his advisors in Westminster. Ramping up the drama are loud, bass-heavy music, thundering explosions and helicopters overhead.

But the evening’s keynote is the pure, mournful voice of a countertenor in black (Henry Jenkinson), who wanders through scenes like a one-man chorus singing minor-key versions of “Jerusalem” and Holst’s “I vow to thee my country`”. Against such solemnity, Falstaff is a welcome disruptor, a life-force with no inhibitions, selfish and dishonest, but hugely entertaining – and apparently highly clubbable: was that a Garrick Club tie he was sporting in the final scenes?

rating

Share this article

more Theatre

Two Strangers (Carry A Cake Across New York), Criterion Theatre review - rueful and funny musical gets West End upgrade

A Brit and a New Yorker struggle to find common ground in lively new British musical

Two Strangers (Carry A Cake Across New York), Criterion Theatre review - rueful and funny musical gets West End upgrade

A Brit and a New Yorker struggle to find common ground in lively new British musical

Testmatch, Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Testmatch, Orange Tree Theatre review - Raj rage, old and new, flares in cricket dramedy

Winning performances cannot overcome a scattergun approach to a ragbag of issues

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

Banging Denmark, Finborough Theatre review - lively but confusing comedy of modern manners

Superb cast deliver Van Badham's anti-incel barbs and feminist wit with gusto

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

London Tide, National Theatre review - haunting moody river blues

New play-with-songs version of Dickens’s 'Our Mutual Friend' is a panoramic Victori-noir

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

Machinal, The Old Vic review - note-perfect pity and terror

Sophie Treadwell's 1928 hard hitter gets full musical and choreographic treatment

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

An Actor Convalescing in Devon, Hampstead Theatre review - old school actor tells old school stories

Fact emerges skilfully repackaged as fiction in an affecting solo show by Richard Nelson

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

The Comeuppance, Almeida Theatre review - remembering high-school high jinks

Latest from American penman Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is less than the sum of its parts

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Richard, My Richard, Theatre Royal Bury St Edmund's review - too much history, not enough drama

Philippa Gregory’s first play tries to exonerate Richard III, with mixed results

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Player Kings, Noel Coward Theatre review - inventive showcase for a peerless theatrical knight

Ian McKellen's Falstaff thrives in Robert Icke's entertaining remix of the Henry IV plays

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Cassie and the Lights, Southwark Playhouse review - powerful, affecting, beautifully acted tale of three sisters in care

Heart-rending chronicle of difficult, damaged lives that refuses to provide glib answers

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

Gunter, Royal Court review - jolly tale of witchcraft and misogyny

A five-women team spell out a feminist message with humour and strong singing

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

First Person: actor Paul Jesson on survival, strength, and the healing potential of art

Olivier Award-winner explains how Richard Nelson came to write a solo play for him

Add comment