That ages-old dictum "write what you know" has given rise to the intriguingly titled My Mum's a Twat, in which the Royal Court's delightful head of press, Anoushka Warden, here turns first-time playwright, much as the Hampstead Theatre's then-press rep, Charlotte Eilenberg, did back in 2002. While some may cry nepotistic foul at a theatre insider grabbing such a coveted perch, Warden has as much a right as anyone to tell a story that in this instance finds an ideally sparky interpreter in the protean Patsy Ferran. Astonishingly, Ferran is delivering the 80-minute monologue twice nightly throughout the run, so whatever else mum may or may not be, the actress playing her daughter, known here simply as Girl, is every inch a star.

More and more movies based on true stories have taken to qualifying their own veracity (Victoria and Abdul, to name but one), and so it proves with this play. Warden says of her own confessional and presumably cathartic account of losing her mum to a cult that the narrative is in fact "an unreliable version of a true story filtered through a hazy memory and vivid imagination". That assessment has the perhaps unintended result of making a spectator doubly curious about what actually went on, and wanting a fuller account of a story that, one imagines, was possibly more ferocious than is indicated here.

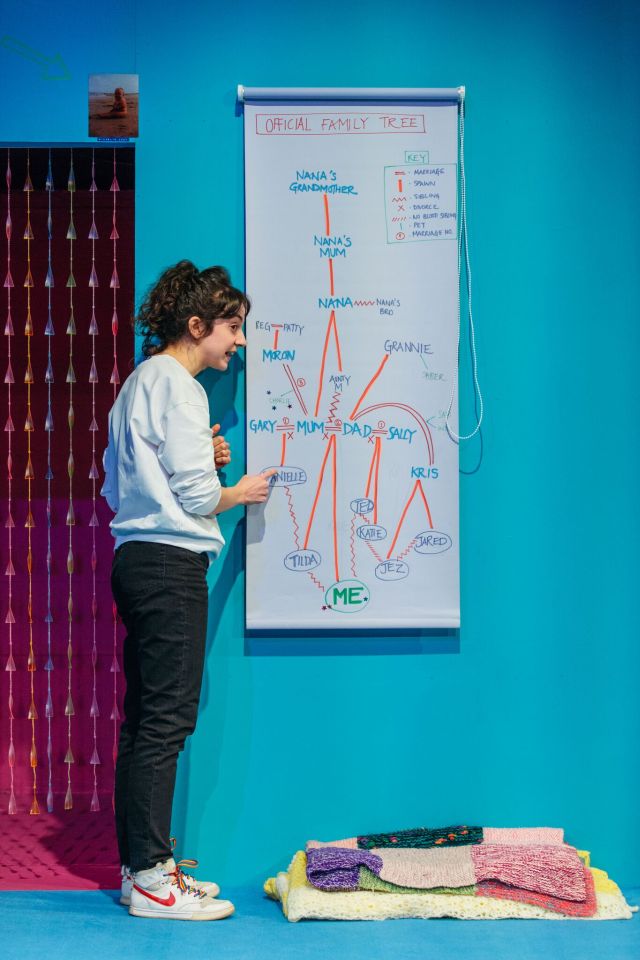

What we get is the immediately enchanting Ferran – her girl-woman features exactly suited to the role – scooping up the intimate confines of the Theatre Upstairs with her saucer eyes as she recalls a childhood that went sour. Born into a labyrinthine network of siblings (at one point, Girl pulls down a chart so we can clock the various parentages for ourselves), this sprightly pre-teen finds herself first having to confront the "total tool" that is her Canadian stepfather, otherwise known as Moron.

What we get is the immediately enchanting Ferran – her girl-woman features exactly suited to the role – scooping up the intimate confines of the Theatre Upstairs with her saucer eyes as she recalls a childhood that went sour. Born into a labyrinthine network of siblings (at one point, Girl pulls down a chart so we can clock the various parentages for ourselves), this sprightly pre-teen finds herself first having to confront the "total tool" that is her Canadian stepfather, otherwise known as Moron.

Before long, both stepdad and the twattish mum are indoctrinated into the dubious ways of the Somerset-based Heal Thyself Centre for Self-Realisation and Transcendence (not its real name). Can Girl reclaim her mum for herself, while preserving her own equilibrium? Therein lies the drama underpinning a project that certainly ends affirmatively for the speaker at least. Girl herself, so the closing moments report (and the ever-cheerful presence of Warden bears out), is doing just fine, and I like the cheeky challenge posed by the final line: "You'll have to take my word on that."

What's missing, one feels, is some sort of twist or complexity to the rather bald-faced narrative voice: the sort of thing that makes such direct address plays as Brian Friel's masterful Faith Healer (a onetime occupant of the Court downstairs) so endlessly rewarding. The details are pungent and varied and range from Girl's gathering fondness for David Jason and gangsta rap on the one hand to her newly awakened 18-year-old self's direct confrontation with the hateful-sounding "guru" who has more or less taken possession of mum. Elsewhere, one simply wants more: if mum is a twat, what about Girl's apparently cold and unfeeling dad, whose rural English homestead offered nothing resembling a safe haven. And one can't help but note the missed opportunity to dramatise goings-on and encounters that simply aren't as potent when reported in passing. It might be interesting if this entire play were recast not as a solo chronicle but as an opportunity for a clash of voices.

That said, I doubt anyone would want to miss the chance to absorb Ferran in such close quarters: a one-person performance that comes, rather unusually, with two directors, Vicky Featherstone and Jude Christian. At times, one feels the implicit pain of the piece being dampened down as if to avoid sentimentaity, which seems odd given the journey from anger towards something approaching acceptance that underpins the piece. (One parallel, on an entirely different scale, might be the Joan Didion/Vanessa Redgrave Year of Magical Thinking.) And having allowed something so private and purgative to be made public, Warden makes one eager to see where her buoyant gift for self-analysis will take her, and us, next.

Add comment