Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten | reviews, news & interviews

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Benjamin Britten’s last opera Death in Venice (1973), adapted from Thomas Mann’s novella of the same name (1912) and the subject of one of Visconti’s later, most celebrated films, explores homoerotic attraction, the nature of beauty and the inescapable presence of mortality.

Britten lay ill, close to death, within sight of the sea, as does the story’s elderly writer Gustav von Aschenbach. The composer was unable to attend the premier in Aldeburgh, in which the title role was sung by his partner the tenor Peter Pears.

The tragic story, in which a famous and burnt-out writer seeks solace in the mythical and liberating “South”, travels to Venice, where he falls for an angelic Polish youth, Tadzio, explores the gulf between beauty as idealised and the beauty embodied in the senses. The opera opens, after a short period of darkness, as if we were waking from a dream, with the author alone at his desk, paralysed by writer’s block. He faces the inadequacy of the words he has depended upon to craft literary beauty, whose source, as he knows deep down, inhabits the real world not the constructs of his cloistered mind.

The tenor Mark Le Brocq evokes Aschenbach’s inner torment with great empathy. His voice never feels forced, and yet, the singer communicates many different shades of emotion very vividly. He is our constant companion throughout the work, with monologues sensitively rendered in recitative with halting piano accompaniment, interspersed with orchestral passages, and the more dramatic scenes that unfold in episodic fashion towards the opera’s tragic end.  Roderick Williams deftly handles seven roles, including the unctuous hotel manager and an over-rouged androgynous figure who taunts the embarrassed writer. He shines in each of them, with his assured baritone and charismatic stage presence. He provides, throughout the work, a dark and comic counterpoint to the psychologically rigid author, both distorting mirror and unnerving Fool.

Roderick Williams deftly handles seven roles, including the unctuous hotel manager and an over-rouged androgynous figure who taunts the embarrassed writer. He shines in each of them, with his assured baritone and charismatic stage presence. He provides, throughout the work, a dark and comic counterpoint to the psychologically rigid author, both distorting mirror and unnerving Fool.

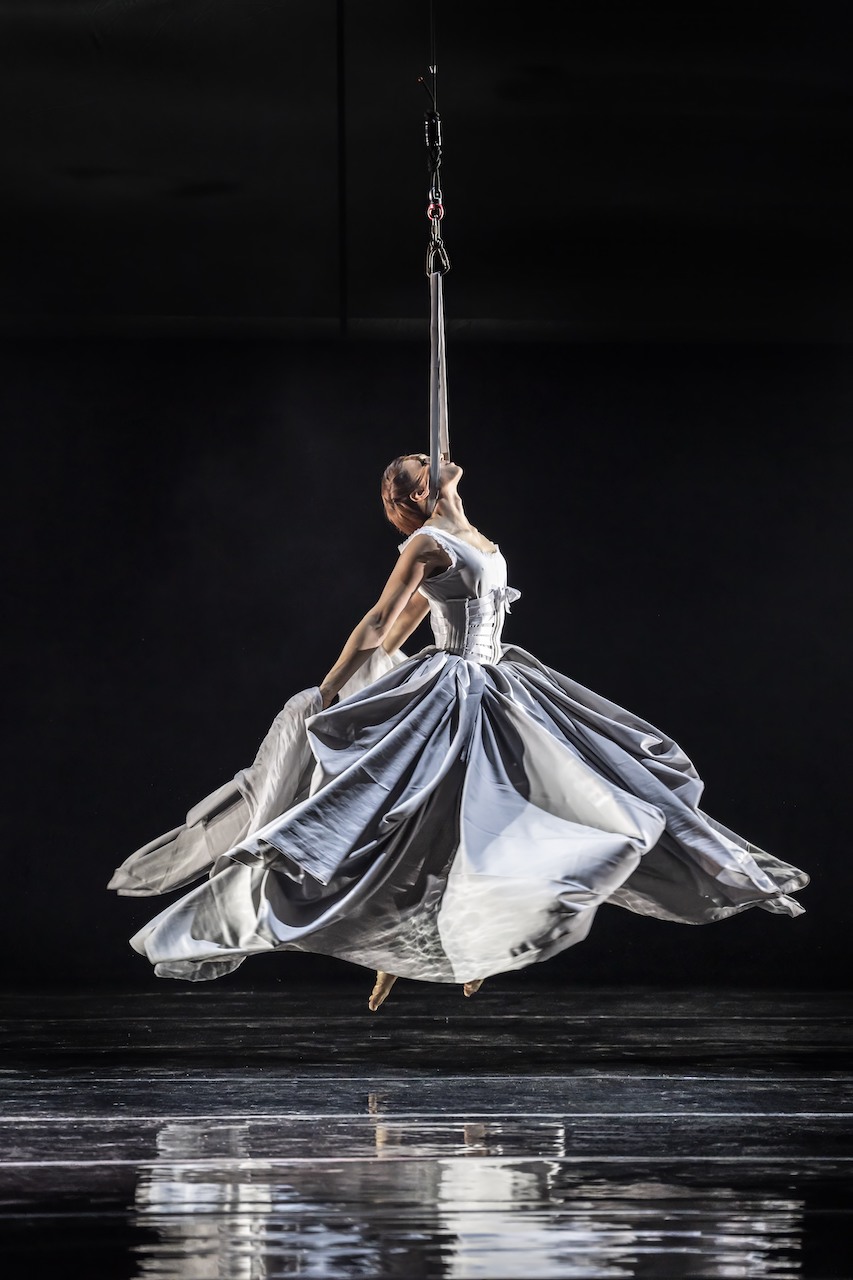

The opera calls for dancers as well as singers, and director Olivia Fuchs has called on NoFit State a wonderful circus and acrobatics company based in Wales. The dancer-acrobats are all wonderfully agile and expressive – virtuosity tempered by an always intelligent sense of emotional authenticity. The star of the show is Antony César as Tadzio, who brings to the role a combination of gymnastic excellence and a feel for expressive movement. Equally impressive is Diana Salles (pictured above), Tadzio's mother, a wonder of aerial dance with a gift to enchant.

With the astonishingly inventive circus designer Firenza Guidi, Fuchs has devised a breath-taking flow of moving tableaux – which are much more than that, as they are constantly evolving images that evoke most perfectly the imaginings of the troubled author, as physical desire gradually takes over an imagination he admits has been at the service of his will. Britten had seen the importance of embodying desire and cast dancers for this opera. Fuchs and her brilliant team – the same - excluding the acrobats – as for her previous WNO production, Janaček’s “The Makropulos Affair” (2022) – follows the composer’s choice with immense flair, drawing on the humour and magic of circus. Most of all, she displays in the playful physicality of the production a deep and visceral sensing of what’s at stake when an uptight intellectual opens up to the senses.

There is often mind-blowing beauty on stage, the stuff of visual poetry made concrete through exquisite lighting, the simple yet versatile set and props, and running through the piece, gorgeous video from Sam Sharples. Video can be misused in opera and theatre. Complicité, Robert Lepage do it very well, and yet there are excesses: as in Peter Sellars production of Tristan and Isolde (2005) in which Bill Viola’s work was much too present and detracted from the very good direction of actors in the foreground. Here, the moving image, in sombre black-and-white is ever-present, but always at the service of emotional shifts in the story – in this case the movements of Aschenbach’s soul. Swirling, almost viscous water, the light playing on its surface evokes the pull between forbidden desire and guilt, more turbulent waves a kind of abandon and potential liberation. Wagner is often associated with the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk, an artistic creation in which different media are meshed in order to produce a whole much greater than the parts. This Britten production does just that, a rare achievement in opera.  Conductor Leo Hussain, not unfamiliar with 20th century repertoire, brings out the richness of a score that shifts from gamelan-influenced textures and tonalities, with expressive percussion to strings with a late romantic feel. His pace complements the unfolding drama onstage beautifully: there’s a show-stopping moment at the start of the second act, when four acrobats swirl above the dramatically-lit stage, with Aschenbach curled up on his armchair, ready for the decision to cut all ties, and be himself fully, no longer halting, in accord with his desire. Light pizzicato strings alternate with heavy low-register chords on strings and brass. The tragic end of the story musically foretold, a kind of trailer for the man’s own death from the cholera epidemic that has engulfed the city and its canals. Everything at this point, visually as well as musically ushers in the growing panic and unleashing of desire that takes the opera inexorably forward.

Conductor Leo Hussain, not unfamiliar with 20th century repertoire, brings out the richness of a score that shifts from gamelan-influenced textures and tonalities, with expressive percussion to strings with a late romantic feel. His pace complements the unfolding drama onstage beautifully: there’s a show-stopping moment at the start of the second act, when four acrobats swirl above the dramatically-lit stage, with Aschenbach curled up on his armchair, ready for the decision to cut all ties, and be himself fully, no longer halting, in accord with his desire. Light pizzicato strings alternate with heavy low-register chords on strings and brass. The tragic end of the story musically foretold, a kind of trailer for the man’s own death from the cholera epidemic that has engulfed the city and its canals. Everything at this point, visually as well as musically ushers in the growing panic and unleashing of desire that takes the opera inexorably forward.

The writer progressively gives way to his unrequited passion, the deadly disease in resonance with the darkest side of the Eros unbound in him. In a dream, Aschenbach is courted by two opposing forces – a Dionysiac figure, dressed in tight-fitting red, and lasciviously played by Roderick Williams, in dispute with the Voice of Apollo in glittering gold. Madness, chaos and the dance of the God from the East wins over the cool solar voice of reason. There is a very powerful moment, a musical explosion, when Aschenbach, who allowed himself to be sacrificed to Dionysus (pictured above), is torn apart and consumed alive by the god and his crazed disciples – as in the ancient Greek myth.

There are many layers to this strange and wonderful opera. Olivia Fuchs clearly connects very sensitively with different dimensions that draw, at the point of origin, from the inner conflicts that tormented Thomas Mann: questions about imagination unbounded and the rigour of form and rational thought, and the life of Benjamin Britten, whose homosexual life was anything but straightforward, and whose desires led him to live as something of an outcast. Fuchs and her team – not to forget the very present chorus, on and off stage, acting with great conviction – have pulled it off. David McVicar in his 2019 production at Covent Garden, with Mark Padmore – so perfect for Britten - and Gerald Finley in the leading roles, did very well indeed, but this production has something else, that runs a little deeper: form and content in more than just accord, but, with a rare mixture of intellect and imagination, granting the work unforgettable emotional power.

Add comment

more Opera

Simon Boccanegra, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - thrilling, magnificent exploration

Verdi’s original version of the opera brought to exciting life

Simon Boccanegra, Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - thrilling, magnificent exploration

Verdi’s original version of the opera brought to exciting life

Aci by the River, London Handel Festival, Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse review - myths for the #MeToo age

Star singers shine in a Handel rarity

Aci by the River, London Handel Festival, Trinity Buoy Wharf Lighthouse review - myths for the #MeToo age

Star singers shine in a Handel rarity

Carmen, Royal Opera review - strong women, no sexual chemistry and little stage focus

Damiano Michieletto's new production of Bizet’s masterpiece is surprisingly invertebrate

Carmen, Royal Opera review - strong women, no sexual chemistry and little stage focus

Damiano Michieletto's new production of Bizet’s masterpiece is surprisingly invertebrate

La scala di seta, RNCM review - going heavy on the absinthe?

Rossini’s one-acter helps young performers find their talents to amuse

La scala di seta, RNCM review - going heavy on the absinthe?

Rossini’s one-acter helps young performers find their talents to amuse

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Death In Venice, Welsh National Opera review - breathtaking Britten

Sublime Olivia Fuchs production of a great operatic swansong

Salome, Irish National Opera review - imaginatively charted journey to the abyss

Sinéad Campbell Wallace's corrupted princess stuns in Bruno Ravella's production

Salome, Irish National Opera review - imaginatively charted journey to the abyss

Sinéad Campbell Wallace's corrupted princess stuns in Bruno Ravella's production

Jenůfa, English National Opera review - searing new cast in precise revival

Jennifer Davis and Susan Bullock pull out all the stops in Janáček's moving masterpiece

Jenůfa, English National Opera review - searing new cast in precise revival

Jennifer Davis and Susan Bullock pull out all the stops in Janáček's moving masterpiece

theartsdesk in Strasbourg: crossing the frontiers

'Lohengrin' marks a remarkable singer's arrival on Planet Wagner

theartsdesk in Strasbourg: crossing the frontiers

'Lohengrin' marks a remarkable singer's arrival on Planet Wagner

Giant, Linbury Theatre review - a vision fully realised

Sarah Angliss serves a haunting meditation on the strange meeting of giant and surgeon

Giant, Linbury Theatre review - a vision fully realised

Sarah Angliss serves a haunting meditation on the strange meeting of giant and surgeon

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera review - compellingly lucid with an austere visual beauty

Bryn Terfel's Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure in this otherworldly interpretation

Der fliegende Holländer, Royal Opera review - compellingly lucid with an austere visual beauty

Bryn Terfel's Dutchman is a subtly vampiric figure in this otherworldly interpretation

The Magic Flute, English National Opera review - return of an enchanted evening

Simon McBurney's dark pantomime casts its spell again

The Magic Flute, English National Opera review - return of an enchanted evening

Simon McBurney's dark pantomime casts its spell again

Così fan tutte, Welsh National Opera review - relevance reduced to irrelevance

School for lovers not much help to the singers

Così fan tutte, Welsh National Opera review - relevance reduced to irrelevance

School for lovers not much help to the singers

Comments

This is a truly wonderful

This is a truly wonderful production. Disturbing, beautiful, with amazing acrobats, indicating spiritual daring behind the physical skill.