Music Reissues Weekly: Playing for the Man at the Door - Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick | reviews, news & interviews

Music Reissues Weekly: Playing for the Man at the Door - Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick

Music Reissues Weekly: Playing for the Man at the Door - Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick

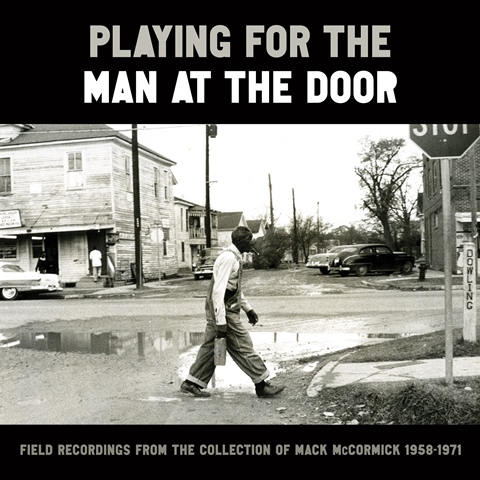

Important box set tapping US folklorist’s previously unexplored archive

Between the late 1950s and around 1971, Robert “Mack” McCormick (1930–2015) travelled through his base-state Texas, Alabama, Mississippi, west Louisiana and parts of Arkansas and Oklahoma looking for musicians to record. It wasn’t a random process: he covered 700 counties using a grid system, so nothing would be missed. As well as tapes, he made lists, filled notebooks and took photos. He kept everything.

After archivists at the National Museum of American History went through what was donated by McCormick’s daughter to the Smithsonian Institution in 2019, they found his collection encompassed, as the fabulous 128-page book coming with the 3-CD, LP-sized box set Playing for the Man at the Door: Field Recordings from the Collection of Mack McCormick 1958-1971 puts it, “over-90 linear feet of manuscripts and research notes, dozens of his fieldwork interviews captured on cassettes, and over 4000 photographs and 590 open-reel tapes. Roughly 290 of these were field recordings of music and interviews conducted during his most intensive blues research period.” The follow-on box set is properly annotated, and there are multiple essays.

Playing for the Man at the Door collects 66 tracks drawn from these tapes. Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb are familiar. Jealous James Stanchell and Kid Wiggins less so. The information on more obscure players in McCormick’s detailed notebooks can be scant, adding little to what was already known. Consequently, some of the individual biographies in the box set’s book are inscrutable. Of Andrew Everett, the full entry reads he “lived in Silas, Alabama, before moving to Texas. McCormick noted that he played in turpentine camps and worked on railroad gangs and in sugar refineries.” Of Dennis Gainus: “From Crockett, Texas, [he] was a cousin to both Blind Lemon Jefferson and the blues musician Jack Johnson. He heard many great musicians passing through his area and learned to play the 12-string guitar from a Mexican émigré named Seville. These are his only known recordings.”

Playing for the Man at the Door collects 66 tracks drawn from these tapes. Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb are familiar. Jealous James Stanchell and Kid Wiggins less so. The information on more obscure players in McCormick’s detailed notebooks can be scant, adding little to what was already known. Consequently, some of the individual biographies in the box set’s book are inscrutable. Of Andrew Everett, the full entry reads he “lived in Silas, Alabama, before moving to Texas. McCormick noted that he played in turpentine camps and worked on railroad gangs and in sugar refineries.” Of Dennis Gainus: “From Crockett, Texas, [he] was a cousin to both Blind Lemon Jefferson and the blues musician Jack Johnson. He heard many great musicians passing through his area and learned to play the 12-string guitar from a Mexican émigré named Seville. These are his only known recordings.”

Two tracks by the enigmatic guitarist Dennis Gainus are heard. “You Gonna Look Like a Monkey” has a New Orleans feel, bolstered by rolling piano. “Old Judge Blues,” recorded on 1 May 1959 is solo, less polished and feels more rural than “You Gonna Look Like a Monkey.” Andrew Everett’s cuts are measured, coming across as a ghostly Leadbelly. Jump in to this box set anywhere and everything will delight, fascinate and thrill.

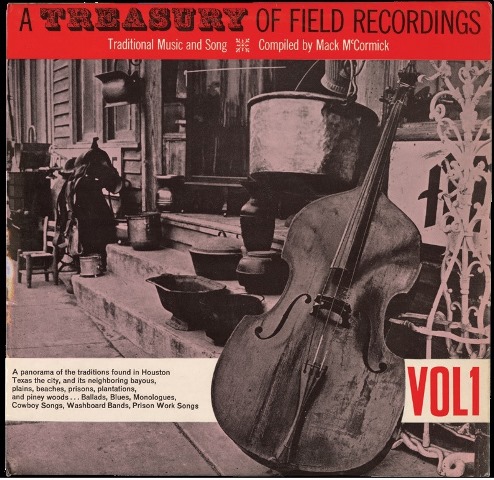

It’s a fitting tribute to this music fanatic. Despite being Down Beat's Houston correspondent from 1948, having worked, in 1949, as a press agent for Texas’ Buddy Ryland Orchestra and regular work with music thereafter – including managing Lightnin’ Hopkins from 1959 to around 1963 – McCormick did his own thing. Sitting outside the music business, he had little interest in releasing much of what he recorded. There was a compilation album titled The Unexpurgated Songs of Men in 1960 and two volumes of Treasury of Field Recordings in 1962 (pictured below left, the first Treasury of Field Recordings album). There were also Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb albums, and one each by Buster Pickens and Robert Shaw. But these records barely dug into the mass of tapes he accrued. It wasn’t just blues he was interested in: barrelhouse, country, gospel and Latino music were also captured by his tape recorder. Although he would go on his field trips with folks working for record labels, McCormick was not a scout.

Amongst his many other endeavours, he also wrote a book about the Robert Johnson phenomenon, titled Biography of a Phantom: a Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey. Characteristically, it sat in the archive and is only being published this year. Until now, the word “phantom” applied equally well to McCormick’s archive. It was known of, but that was about as far as any knowledge went.

Amongst his many other endeavours, he also wrote a book about the Robert Johnson phenomenon, titled Biography of a Phantom: a Robert Johnson Blues Odyssey. Characteristically, it sat in the archive and is only being published this year. Until now, the word “phantom” applied equally well to McCormick’s archive. It was known of, but that was about as far as any knowledge went.

All this implies being driven by the impulse to document what might vanish if it were not captured. The book goes into McCormick’s life and personality. Obsessive? Probably. What’s revealed paints him as a singular, troubled character. For example, this tale: “In August 1949, just when he had begun to establish his bona fides and lay a foundation for success, Dallas police arrested McCormick for forgery. A local newspaper reported that officers found in his hotel room ‘a check-protecting machine, about 50 drivers’ license forms, various blank checks, and a memorandum book in which he kept notations of cashed checks.’ He cooperated with police and confessed to keeping additional forgery equipment in Houston, where police found in his room ‘rubber stamps with names of Houston business firms and street addresses.’”

There’s this snapshot too: “In 1965, Alan Lomax encouraged the organizers of the Newport Folk Festival to recruit Mack to find and deliver for the festivalgoers’ edification a gang of incarcerated people who would sing work songs while actually chopping wood, demonstrating the unfree, uncompensated labor they provided daily to the state of Texas. The state’s attorney general declined Mack’s request, so instead he assembled a group of men recently transitioned from prison camps to halfway houses and drove them to the festival. McCormick later claimed to have pulled the plug when Bob Dylan’s ‘gone electric’ soundcheck cut into his group’s rehearsal time.”

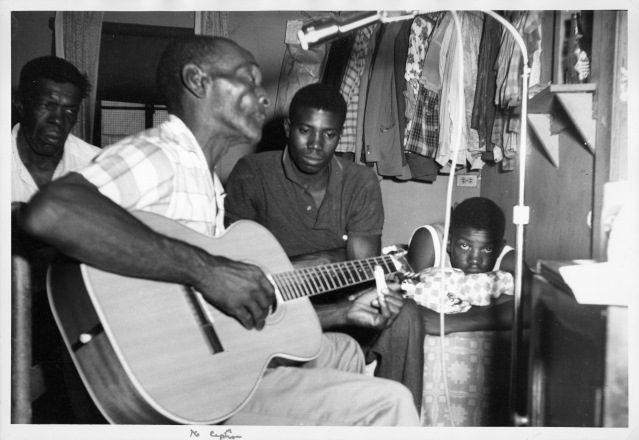

Implicit questions are raised by Playing for the Man at the Door about the issues framing the white-black dynamic. These are met head on in the text. Given what McCormick did and did not do in terms of propagation – and taking into account his distinctive character – there is nothing simple here. (pictured right, Mance Lipscomb with family. Photo by Mack McCormick. Robert “Mack” McCormick Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

Implicit questions are raised by Playing for the Man at the Door about the issues framing the white-black dynamic. These are met head on in the text. Given what McCormick did and did not do in terms of propagation – and taking into account his distinctive character – there is nothing simple here. (pictured right, Mance Lipscomb with family. Photo by Mack McCormick. Robert “Mack” McCormick Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution)

In an essay titled Thoughts on Mack’s Collection, Dom Flemons eloquently wrestles with McCormick’s motivations. Flemons ends by saying “Mack McCormick’s mental health began to deteriorate in the years following these recordings, [and] he carefully kept under wraps his collection which he dubbed ‘The Monster,’ refusing to let anyone see or hear his sources, skeptical of others’ intentions. Playing For the Man at the Door is a reminder that we still have a lot to learn about the blues.”

Collectors should note that, including Gainus’ “You Gonna Look Like a Monkey” and the Everett cuts, 15 of the box set’s 66 tracks first appeared on the two Treasury of Field Recordings albums. Given the scope of the McCormick archive, couldn’t everything here have been previously unreleased? Clearly though, Playing For the Man at the Door: Field Recordings From the Collection of Mack McCormick 1958–1971 is a major release. It is also vital reminder that context is essential and that, so often, music about more than the tunes.

- Next week: Thirty years after it first hit record shops, The Boo Radleys’ Giant Steps returns

- More reissue reviews on theartsdesk

- Kieron Tyler’s website

Buy

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Music Reissues Weekly: Joe Meek - A Curious Mind

How the maverick Sixties producer’s preoccupations influenced his creations

Add comment