On 25 November cinemas all over Britain and overseas will host a live relay from the Bolshoi Ballet of a rampantly OTT and enormously entertaining ballet set in ancient Egypt, The Pharaoh's Daughter. It has mummies coming to life, English tourists in timewarps, frenzied cobras, underwater ballets, jaunty tunes, and phalanxes of delectable archeresses. The original ballet premiered exactly 150 years ago, and what you'll see is a recreation of the fantastical, surreal exotica of the kind of theatre provided at the dawn of classical ballet. It is a sight that had been thought lost until 12 years ago; for it's not just the pharaoh's daughter who's coming to life in the story, the ballet itself is a bit of a mummy too.

As any archaeologist knows, digging up a sarcophagus is a nailbiting business. What are the chances that inside the shredded linen wrappings will lie a recognisable body with some scant flesh upon it? Enough to reconstruct the living person's age, state of health, status - perhaps even enough detail on the face to bring the dead features back to life and a guess at personality? Properly mummified, a human body can yield an extraordinary amount of living information after thousands of years. Ballets vanish far quicker.

Stop performing a ballet for a decade and a generation of dancers is lost who knew it. Stop performing it for 25 years, and a generation of audience and new leaders has hardly any idea it had existed. Even the most opulent, luxurious ballets of the masters are not invulnerable, as ballets have never adopted the written traditions of classical music and drama, where texts are set down on the record. And nowhere does this perishability more crucially affect the art of ballet than the fate of the works of its greatest master, the Frenchman who over half a century created the gold reserves of the 19th-century classical ballet artform from his position in the courts of the Tsars of Russia in St Petersburg - Marius Petipa.

The choreography we see has been handed across decades from one memory to another, with a rewrite here, a substitution there

We know Petipa (or think we do) from a very small number of familiar landmarks - The Sleeping Beauty, La Bayadère, Don Quixote, the brilliant court acts of Swan Lake, less familiar glimpses of Raymonda and Paquita. But the choreography we see in various productions has been handed across decades from one memory to another, with a bit of this and a bit of that, a wholesale rewrite here, a modern substitution there. Perhaps one sees two-thirds of the original text, if one's lucky; less than half of it is common enough. This is why Nutcrackers and Sleeping Beauties vary so much from company to company.

Not until the discovery only a dozen years ago that some aged volumes of code, stored in the Harvard Theatre Library in the US, actually held verbatim notations of two dozen of Petipa's ballets (notes made on his command) did the possibility surface of decoding, recreating, reconstructing his productions in their original style. Since then a new movement has arisen (amid considerable argument) to consolidate and fix the true Petipa choreography of the 19th century, and even to try to reclaim ballets thought lost, such as his first major ballet, The Pharaoh's Daughter.

It was Petipa's choreographic debut in his adopted new homeland of Russia, in 1862 (left, young Petipa). Its colourful travelogue location and fast-footed romantic comedy made Petipa's name, and set a pattern that he cannily capitalised on with his next two smash-hit ballets, Don Quixote (the Spanish one) and La Bayadère (the Indian one). These two ballets made it through time to future eras, but not The Pharaoh's Daughter, which was thrown out with the trash when the Russian Revolution caused a swift revisionism across all cultural artefacts.

It was Petipa's choreographic debut in his adopted new homeland of Russia, in 1862 (left, young Petipa). Its colourful travelogue location and fast-footed romantic comedy made Petipa's name, and set a pattern that he cannily capitalised on with his next two smash-hit ballets, Don Quixote (the Spanish one) and La Bayadère (the Indian one). These two ballets made it through time to future eras, but not The Pharaoh's Daughter, which was thrown out with the trash when the Russian Revolution caused a swift revisionism across all cultural artefacts.

Being the maestro's wildly lauded opus 1, The Pharaoh's Daughter became the equivalent of a lost royal tomb in Luxor, the subject of curiosity as, late in the 20th century, the notion of doing some ballet archaeology started to become current.

Pierre Lacotte was a former Paris Opera Ballet star who had won himself the gratitude of balletomanes worldwide when in 1972 he recreated the first Romantic ballet, the original La Sylphide - not the one known to stages today by August Bournonville, but its predecessor by Filippo Taglioni, the ballet that introduced to the public the ethereal, floating figure of his daughter Marie Taglioni, a vision that became the icon of a whole cultural movement across the arts, from literature to opera.

He had found historical texts for that groundbreaking Sylphide in the Louvre Museum. In the late 1990s the news that the original ballet texts of Petipa had been found, stored in America, and were being decoded set alight a flare of curiosity about the possibility of retrieving dozens of St Petersburg's legendary balletic pageants.

He had found historical texts for that groundbreaking Sylphide in the Louvre Museum. In the late 1990s the news that the original ballet texts of Petipa had been found, stored in America, and were being decoded set alight a flare of curiosity about the possibility of retrieving dozens of St Petersburg's legendary balletic pageants.

While the Kirov Ballet hastened to clean up existing known ballets, The Sleeping Beauty and La Bayadère, the Bolshoi Ballet hatched the idea of retrieving Petipa's Egyptian fantasy-romance from the lost tombs of time - and they called on Pierre Lacotte. The result charmed the public and dancers alike, and has become, after its long oblivion, the most durable yet of all the reconstructions attempted.

Yet what is it that we see? The name on the credit is not Petipa's but Lacotte's. That curious fact betrays a fascinating story of the caution, honesty and daring creativity that ballet reconstruction entails. It is 40 years since Lacotte did his first reconstruction; since that beguiling Sylphide appeared from the darkness in 1972, he has disinterred - as faithfully as he believes possible - several works from that elusive first half of the 19th century when ballet was in high Romantic period. But as he explained to me when we met in Paris in 2004, the pitfalls are many when you go digging.

This year Lacotte turned 80, and the presence of The Pharaoh's Daughter in the Bolshoi Ballet repertoire this year as well as his similarly reconstructed Ondine at the Mariinsky Ballet are apt birthday tributes to the ingenuity with which he tackles trails into ballet's history, trails as convoluted as any journey to find a lost pharaoh's tomb.

Q&A with Pierre Lacotte starts on the next page

ISMENE BROWN: When did this all start?

ISMENE BROWN: When did this all start?

PIERRE LACOTTE: A long time ago I was working with Lyubov Egorova and she would talk about this ballet, The Pharaoh's Daughter. She had worked with Marius Petipa, and she said it was wonderful - there were so many things to dance in it, and a nice story about travelling in Egypt. We talked a lot about it - she always said she wanted to show it to me. Well, I was living very near Mathilde Kschessinska [Petipa's most famous ballerina], the other side of the road, and she says, "Why are you working with Egorova, you are so close to my place?" I said, "Because I like Madame Egorova. She's always talking about The Pharaoh's Daughter, how the Petipa style there is so different from what is known in other ballets."

And one day Rudolf Nureyev, the director here [at Paris Opera Ballet], told me, "Listen, Pierre, think about doing the Pharaoh's Daughter." And I started to look all around the world to find what there was [of the choreography], and we talked again at the Paris Opera, and they said it would be so expensive, so many sets and costumes - and they gave up.

I was in Moscow a bit later with my company when I was director of Ballet de Nancy, and we did [Lacotte's reconstruction of] La Sylphide, and in an interview I was asked what I would like to do next. I said, "I'd like to do Ondine and Pharaoh's Daughter." That got to the ears of [the then Bolshoi ballet directors] Vladimir Vasiliev and Alexei Fadeyechev. Fadeyechev reached me by letter and said what if we invited you to do Pharaoh? I said, "Good idea, but be careful because it will be very expensive." They said, "Don't worry about the money, Vasiliev is very interested in this production."

So first I went to St Petersburg and asked the older dancers whether they remembered anything of the ballet. I knew there was also the notation of Stepanov now so I thought we could do it. I asked a friend living in America [Douglas Fullington, a specialist in Stepanov notation] to send me a video [of a sample of reconstruction]. But I was surprised, because he said, "You know, not everything is right in the score. Sometimes you have the arms, sometimes the legs, it's difficult to get it." Well, two variations were very clear, two girls in the pas d'action. I accepted them, and I asked him to do the River [scene]. So he did the Rivers. But I'm sorry, when I saw it, it just was not right, it was not clear, it was, like, two steps here and nothing else - and I know Petipa. I said, I'm sorry, I don't want that, the notation isn't very good.

Then I thought, maybe I'd ask [the ballerina Marina] Semionova, who was the last one to dance it, what she thought. And she said, "Forgive me, you know my age? I am 91, I danced it twice in 1927 and I can't remember it. But listen, I'll give you good advice - you know the style, you know all the ballets of Petipa very well, do it yourself. Pay respect to the style but do it yourself." So that's what I did.

I understand that the Harvard collection score of The Pharaoh's Daughter has 250 pages, which is a lot. You went through this and was it not good enough?

Not good enough. It is good for Sleeping Beauty, La Bayadère, and many other ballets, but for Daughter it was only good for [the balletmaster's] memory. There are a lot of notes, which I used, but choreographically it's not in detail. For instance it might say, she arrives on the right or she arrives on the left, or she is in the centre. What can you do with that?

You expected more detail? That must have been daunting. Because with [Taglioni's] La Sylphide you had a lot of notes.

Yes, I had more for Sylphide.

Is that one Lacotte-after-Taglioni or did you recover the original choreography?

Yes, mostly. Just a few things I did.

It must be such a thrill to look back 180 years when you're doing that work.

It is fantastic. I want to tell you something. In the second act I had a lot of things known, except for the entrance of Marie Taglioni herself as the Sylphide. I looked at the sets and I thought, well, it's strange, but here is a rock, and I think this is where she must have entered. Well, when I was visiting St Petersburg, the director said he would open his archive to show me everything he had of La Sylphide. He opened the book - and the entrance of the Sylphide in Act 2 was exactly as I imagined! You have no idea how thrilling is that kind of thing. It's strange, but it's true.

Feels like a supernatural connection.

And something else. I knew that Marie Taglioni's son Gilbert des Voisins had gone to the Louvre and gave them various documents, so I went there and asked, and they said, "Yes, it's true, but there's no numbering or indexing in the stores." There were thousands of documents without numbers. He said he would give me a month to look at them. I went in and I spent a month there, but right up until the last day I found nothing. And with just one hour to go, I suddenly found, I picked at random, the material. It was just fantastic.

Everything of the choreography I found with Sylphide was written by actually naming the steps, it was not a notation. And though I had a lot of empty parts, there was more detail than I found for Pharaoh. I was of course very disappointed with the variance between them. But it was the same with the Pharaoh sets and costumes - I found certain things were complete, one set here, and another one would be from a completely different period. It was not a [design scheme] clear from the beginning to the end. It would be a little bit of this and a little bit of that, quite a mixture of tastes, if you tried to recreate that production (pictured right, Mariinsky ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska as Aspicia in The Pharaoh's Daughter).

Everything of the choreography I found with Sylphide was written by actually naming the steps, it was not a notation. And though I had a lot of empty parts, there was more detail than I found for Pharaoh. I was of course very disappointed with the variance between them. But it was the same with the Pharaoh sets and costumes - I found certain things were complete, one set here, and another one would be from a completely different period. It was not a [design scheme] clear from the beginning to the end. It would be a little bit of this and a little bit of that, quite a mixture of tastes, if you tried to recreate that production (pictured right, Mariinsky ballerina Mathilde Kschessinska as Aspicia in The Pharaoh's Daughter).

Is it possible to make a more authentic version from the notation of Pharaoh than you did?

Yes, of course. Because when Rudolf asked me to do it, at that time Felia Doubrovska was alive, and she had been in the corps de ballet for Pharaoh's Daughter in St Petersburg. She said she would help any time, if I needed it, but she died soon after. I did it too late, probably.

So when you started with Pharaoh, you looked through all this stuff, knew you'd have to choreograph it yourself.

Yes.

Did you think you'd have to give up, because it wasn't what you expected?

No, when you are approached you have to be honest and not lie about it. If you want to do this kind of ballet, if you have a lot of love and sincere respect for the style of the period, you can do it, but you have to say it's in the style of Petipa but it's my choreography. And that's what I did. But at the beginning, I'd thought with all those notes in the Stepanov notation, ah, I've got the original. Douglas (Fullington) was very sorry about it, but I told him afterwards, "Look, if something isn't clear in the middle, how can I use it?" And when I saw the River variations, I said, "Douglas, this isn't possible, it cannot be true. Even in the music - it was for a school, not for a ballet company."

There are nearly 30 years between The Pharaoh's Daughter and The Sleeping Beauty, and Petipa's style must have matured and changed a lot. Was that difference recorded in those late 19th-century notations?

Yes, because when Petipa arrived in St Petersburg he came straight from the French school. Immediately he started to work on his first big production, The Pharaoh's Daughter. After that he started to change and be influenced by what he did with Cecchetti, but what I was told everywhere is that when he arrived he was doing it in French style.

Yes, which leads on to how you style the dancing, not just mastering the steps. The Bolshoi dancers told me it was very difficult.

Yes, which leads on to how you style the dancing, not just mastering the steps. The Bolshoi dancers told me it was very difficult.

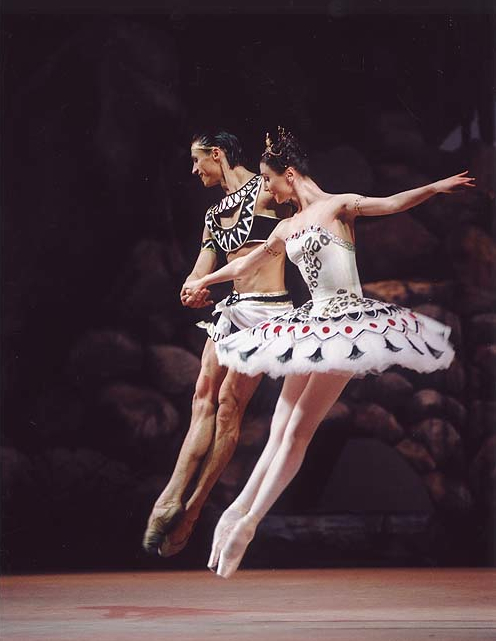

At first, yes, but you see the difference now - they understand it and they like it (pictured, Svetlana Zakharova and Sergei Filin from the Bolshoi film).

What's the biggest difference in style between 1860 and today's classical performance? Is it carriage? Femininity?

Yes, with the beginning of Romantic ballet they tried to do something completely different in feeling. Before [Taglioni's] La Sylphide, people expected a demonstration of technique, a very strong presentation. La Sylphide started something better, which was to make the very difficult look very easy - it was in that period of French style and interpretation of movement that Petipa was starting. You know, his brother was the first Albrecht in Giselle and very close to him.

But I want to say another thing about notation. I was very surprised when I saw the Mariinsky Sleeping Beauty, very very surprised. Happily surprised in some things, very badly in others. I think when Nikolai Sergeyev did the reconstitution in Sadler's Wells with Margot Fonteyn, that was very close to the original, because Egorova danced Aurora as well, and what she showed to me and everybody was exactly the same as what Margot did. But the reconstitution of Sleeping Beauty now - the tempi are wrong, the steps are strange. For instance, in the pas de deux, they went much slower, and it's not Petipa. That's what is strange - I wondered if it was just badly written down or else not understood and then changed.

Sometimes Russian conductors play ballet music far slower than we do in Europe or America.

The corps de ballet was all right, but the principals - I'm not sure. I would like to talk with the person who did it there.

Sergei Vikharev?

Yes

He danced in your reconstruction of La Vivandière, I heard, it was where he started his interest in reconstruction.

Yes, but may I tell you something honestly? Oleg Vinogradov called me once and said come and see these two new dancers, and they showed me Vivandière. And I said to Oleg, "Why on earth has this choreography been changed?" I corrected it. It should be on the right and it was on the left, and this was changed to that. And I said to them, "Why you do this?" They said, "Well, it's very difficult like this." And I said, "I want you to do the choreography, you are not bad dancers, why change it?" But when they did it again, they started to change it again.

Look, you have to be clear with the audience what they are seeing. When you don't have the choreography, let everybody know

Another example. You saw the Petrushka in St Petersburg? You think it's possible for Petrushka to do this big solo? How could you make this strange big solo with grands tours to the left and grands tours to the right? Petrushka can't dance like that, he is [he mimicks a soft doll]. If somebody is able to change it, you cannot say this is Fokine - you can say it is "after" Fokine or something. In Paris everyone was very shocked by the new Petrushka.

And the same thing in Sheherazade - they do a pas de deux, but this pas de deux did not exist originally. And there's a wonderful carpet of Bakst for that ballet, wonderful colours, it looks like a miracle when all the dancers arrive - but they say, "Oh, the dancers don't like the carpet." And I must say, "Well, how could you say sets and decoration by Bakst when it is not? And Zobeide is supposed to be in white - so why is she in green now?"

Look, you have to be clear with the audience what they are seeing, it's important to respect the past, and when you don't have the choreography, okay, but let everybody know. They [the Kirov] did Chopiniana very well, wonderful. And a wonderful Polovtsian Dances, absolutely Fokine, absolutely Fokine. But Sheherazade and Petrushka... [makes a face].

I think authenticity and reconstruction is a very important issue. It's important for people to agree what is right.

Of course.

In Moscow I was talking with [veteran dance historian] Elizabeth Souritz; she said you can't find people in agreement about it there, teachers or professors or dancers.

It's very difficult, but it's much better in Moscow now. I adore the Leningrad school, for me it's the passage between French and Russian schools, it's the story of dance. But I think now they are getting it right in Moscow, and I'm surprised (pictured left, latest cast in the Bolshoi's Pharaoh's Daughter, Olga Smirnova and Semyon Chudin).

This question of defining authenticity. I'm a musician - in music everyone used to play Bach like Brahms, Prokofiev like Beethoven, but then the authentic movement cleaned up people's attitudes, provoked new stylistic sensitivity, it did a wonderful thing. This should happen to ballet.

This question of defining authenticity. I'm a musician - in music everyone used to play Bach like Brahms, Prokofiev like Beethoven, but then the authentic movement cleaned up people's attitudes, provoked new stylistic sensitivity, it did a wonderful thing. This should happen to ballet.

I agree completely. I think what is interesting in music, dance or theatre is to present everything in its different style, if you do Romantic period or baroque style and Fokine - I adore Fokine. Otherwise everything will look the same.

And it's stimulating for the artists too.

But you know, it's not the fault of the Russian dancers. They were educated in a certain way to think "you are the best, everything you do is much better than anywhere else." And if you show the choreography of the film of Petrushka - the right one, and the one they do - they will say, yes, maybe, but our version is more interesting. That's their last word.

Because in Russia they have had that eternal tradition of changing things, never writing things down, no fixed text, each teacher coaches the pupil to change the classic to suit them. So Swan Lake keeps changing.

That was only after the Revolution, because before it they wrote everything down. Except the coda - in which Petipa accepted changes to certain steps for the stars, and they changed the variations.

So when Petipa saw a ballet, he would take the story and concept, but take a new composer and make his own completely different version. Whereas in the 20th century Soviet era people just change one bit here, and one bit there, and the old thing gets pushed around. Swan Lake changes and changes, and look at Nutcracker, what is Nutcracker now?

All the ballets Alicia Markova danced, that was all the correct choreography of Petipa and Ivanov. At that moment it was clear, and if you talked with her or Egorova or Preobrajenska or Kschessinska, they said, yes, it's the same. But then later as certain stars wanted to change it, even after the Revolution they didn't respect anything any more.

It's now become the set tradition. The teachers like their oral tradition, they don't want to record things the way Mozart wrote his scores. Even when Balanchine was alive he changed things, but when he died we know there are now set choices. With Ashton there are more problems. The thing is, if historians and teachers and theatre directors don't agree about the value of authenticity, what happens to it?

It's difficult to know about the future, but now we have so many possibilities with technology and notation to try to fix the choreography, style and work of the past. And teachers are not choreographers.

But they are very powerful - particularly in Russia.

The coaches are. But I think they are starting to learn the steps and to respect style more now.

Let's talk about the differences between early Petipa and late Petipa. Women were different physically (pictured, Maria Alexandrova as Ramze in Pharaoh's Daughter).

Let's talk about the differences between early Petipa and late Petipa. Women were different physically (pictured, Maria Alexandrova as Ramze in Pharaoh's Daughter).

That's right. It's a question of interpretation. The legs are higher, that's true.

They didn't look like they do now.

That's true. Except, no, look at pictures of Pharaoh with Anna Pavlova...

Yes, true, but does it bother you? I mean, I hate it if I see a girl in Giselle sticking her leg up high. I want to scream.

Oh, I agree completely with you, I scream. I see this in Sleeping Beauty [leg vertical] and I say to her, what are you doing? That is a wrong step. That is a very bad way of dancing. If you start not respecting style, you can't respect yourself, and nobody will respect you. I think if the girls don't understand the style, they should stop dancing it.

That doesn't stop them. Zakharova tells me she must put her leg high because the public expects her to. She says, the audience's eyes have changed today, and they won't be interested if they aren't given what they expect.

Of course not. Crazy. I'm sorry, but no, it isn't true. Of course people will accept it, if it's done with emotion and belief - it's crazy to say that.

What is the best thing to say to a young modern girl to throw her mind back?

Stop thinking how you live now; try to remember how girls were then, try to have good shoes, good education, talk slowly and listen to others; go to museums and read the subject; give me your hand and let me teach you Petipa. Afterwards it will be like having new gloves in your size and putting them on.

That's one big sticking point for reconstructing 19th-century ballets - the ballerinas! The other is the leading men, who have so little to dance in late Petipa.

No, they danced, they danced. In the period of French romantic ballet the male dancer was very very important.

There was a lot of male dancing in Pharaoh's Daughter, which surprised me.

Yes, it surprised you. But one of the two variations for the boys in the pas d'action was the original one; the other is by Gorsky. There's a very strange story - Alexander Volinin from the Bolshoi was a teacher once here in Paris, and Jean Babilee told me, "I know a variation from Pharaoh, the pas d'action." He showed me what he was taught by this Bolshoi man. So I put it in!

When Babilee showed you that variation, and when another dancer showed you a variation, did you have to check that against notation to see if it was original, or did you just accept it and put it in?

I took it. This Ramze variation is made by Madame Preobrajenska [who demonstrated it to Lacotte] but there is no notation. Of course you could see the style was right. She was sure of the original version because they kept it as a solo in examinations (below, Maria Alexandrova as Ramze dances this genuine Petipa solo in the Bolshoi film).

If you had to make an argument for or against establishing all the originals of all the ballets we can - from the Sergeyev notations - would you be for or against?

For it, with respect. But against, if I think it's not correct. I don't want to destroy the memory of Petipa by using a variation I think is poor, like the River variation.

Do you think Petipa checked the notations to see they were correct?

No, he had no time, he trusted Sergeyev. He made his own notes as named steps, not notation.

And drawings?

Yes.

I thought some of those corps de ballet groupings looked as if they'd been drawn! Like flowers or statue groups.

Yes, exactly.

Above, Aspicia falls into the River Nile - one of the notated scenes that Lacotte chose to substitute

Was Sergeyev reliable?

Yes, completely. Two things: he had a fantastic memory. He adored Petipa, and if his memory was not clear he could produce his book of notations. Even if he wasn't clear in his notes for us, when he says, she arrives on this side, he knew the steps in his mind clearly. Certain ballets like Bayadère are absolutely clear from beginning to end, everything.

Do you like the Mariinsky reconstitution?

Yes, but I don't like everything - I would cut certain things, like the little child at the end, not interesting to me. What do you think?

I think sometimes I accept something danced by Russians but not by others!

I agree! [laughs]. When Sergeyev came to Paris Opera teaching, he did it very well, and I kept these versions in my mind, because I saw and enjoyed them. And I talked with Spessivtseva who was in America, and she said, "Keep it, it's right." And when he came to London he did Swan Lake and Nutcracker and Giselle for Sadler's Wells, and they were absolutely correct.

Swan Lake must have changed more than any of the others over time.

Oh yes, because in Russia they changed everything.

Your Nancy version [of Swan Lake] was a reconstitution of Petipa-Ivanov?

Yes.

All the people who do research should agree together how to keep the tradition and history. Because if dancers and teachers decide what is done, they will change everything

But if your Nancy version is the closest and most faithful, should not all the other versions be thrown away? It's like saying Shakespeare's Othello is only a basis for other people to change it. Once you fix the original and true one, the others must be thrown out.

I think now we must try to cooperate between all the people who do research to agree together, to find a good way to keep the tradition and history. Because I am worried. If dancers and teachers decide what is done, they will change everything - like they've done all this time in Russia.

In 50 years' time how much will be left of Swan Lake if nothing is fixed?

I'm afraid now something must happen. We have to find a solution, to get together and say "okay, you can do all you want to change - but we must at least reconstitute the originals to film them, for instance, to have it documented." If people are crazy enough to change these classics, I think it's better they do something radical like Mats Ek with Giselle.

As William Forsythe said to me, it also subverts creativity, because people instead of writing completely new ballets just use their energy on tinkering with existing things. You should ban tinkering, he said.

I agree completely, I agree, I agree.

But it seems to be an argument very hard for coaches and dancers to accept.

But teachers are teachers, not choreographers.

But they are so powerful.

Well, why don't spectators stand up and demand teachers run things? Teachers are teachers, coaches feel they always must respect their tradition.

So the logical extension of this is that the Mariinsky originals are now set as the text for Sleeping Beauty and Bayadère, and all other versions should be thrown away. But there would be a riot in theatres.

Yes, there would. But things have already happened. Giselle, for instance, was originally much longer. If it was cut, maybe it was for useful reasons. The Bayadère, for instance, is better, for me, shorter - because it has more life.

The audience is like a child. If you tell a good story to a child, it listens to you. If you don't know how to read the story, the child loses interest

Peter Martins [New York City Ballet ballet-master] thinks Sleeping Beauty is better if it's shorter, which allows people to get home to the TV. It's a powerful vote, the audience.

Two things. The audience is like a child. If you tell a good story to a child, it listens to you. If you don't know how to read the story, the child starts to play with things and loses interest. If you know how to take the audience in your hand and bring them to the stage, make them sleep or dream, that's the point. If the performance is good, it's good. When I was young I was in love with two people, Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh, and I saw everything they were in, and for me it was always too short. If you know how to play, if you know how to dance, people follow you.

Then the Bayadère, four hours long, must be kept - you have to be consistent!

Maybe... for instance, let's say with Bayadère. If Sergei Vikharev was working with a good choreographer, brought the score, if he'd got Mr Frederick Ashton working with him, it would be better. If you just have a good student who reads Stepanov and puts this on stage, that's no good.

This is my argument against the Hodson-Archer Nijinsky so-called restorations. The choreography is completely lost, so they choreograph it.

Do you like it?

No, I hate it. Because they are professors, not choreographers. I don't want to judge Nijinsky's genius from their Sacre.

The only thing of Nijinsky that is absolutely right is L'Après-midi d'un Faune.

But that holds the theatre, I think, but Jeux is fake. And Sacre really worried me.

I saw Sacre du printemps and I thought it was a good performance.

But I think their methods are problematic because they have no choreography there, not even the beginnings of notation - they have photographs, drawings, writings. I have the same problem with reconstituting Petipa, because I ask, "How much Petipa is actually here?"

You are right, and that's why I don't want to lie.

I asked Svetlana Zakharova (pictured right) what Petipa was to her, in terms of the great classics. Effectively I think she felt that Petipa's choreography was less important than "Petipa-style" because the original choreography isn't properly established. I was really worried by this.

I asked Svetlana Zakharova (pictured right) what Petipa was to her, in terms of the great classics. Effectively I think she felt that Petipa's choreography was less important than "Petipa-style" because the original choreography isn't properly established. I was really worried by this.

Yes, that would be a wrong mentality. But I assure you when I was working with Zakharova on Pharaoh and said I'd change something for her, she said, "No."

But I was trying to picture the tradition in which she is working. How the dancers think. There was apparently a damaging argument about Balanchine style in the St Petersburg school... Gabriela Komleva said, "Balanchine came from us, and the way we do it is best."

That was really stupid, that. Balanchine did come first from St Petersburg, but he did everything in evolution in America, and we have to follow him there, not the style of St Petersburg, because he changed it completely. And bring it back and be proud. Of course it's a new language.

You specialise in 19th century ballet, but do you worry about 20th century choreographers and reconstruction questions? Or did the 20th century give us a clearer idea of what text is?

Yes, in a way it's clearer. But very few people can do this kind of work, and they don't have to argue between each other. The best thing is for people to get together. Everybody has something to say.

Life is too short to disagree, we all love ballet and must talk nicely and give to each other, try to help each other

I know there are disagreements around the world about how to read the notations, and whether they are full enough, and whether it's even relevant to recreate fragments.

You have to respect everyone else. For instance, Ann Hutchinson knows very well how to describe things - she was not a ballerina, but she is often right. I think life is too short to disagree, we all love ballet and must talk nicely and give to each other, try to help each other. I don't go in for competition. I think it's wrong to be too proud of yourself, wrong to say, "I'm right, nobody else can be right." Why is it interesting to talk to you when you have an opposite view and you are trying to know more? That is better. There are ways to talk with each other, even when you disagree. I'm so worried when I see people saying, "This is best, that is not." We have to respect each other, and talk to each other.

So what would you say if someone said, I can do a more authentic Pharaoh's Daughter?

Do it!

In the end, will there be many more reconstructions? They are tiring and very expensive, and few people know how to do them.

We have to be the testing ground for younger people to try to do it. I'm sure there are a lot of ballets very ripe for reconstitution, but we don't know exactly where they are. And you said something very important - it's all about finding the style of a period. The steps may be the same but they are done in different style for a period and for their music. I know the style of Fokine and Perrot and Petipa, and I want to explain this to people. Just as Ashton is absolutely a style; I knew him, he could talk about Pavlova for hours and hours and hours. Each choreographer has something to say of their own, and we need to find people who can respect and understand that choreographer. But if you just find steps correctly without the tempi, with the expression, without the punctuation - of course that's not right.

I would like to pass my enthusiasm to younger people and dancers to do this. I have a young girl working with me. Maybe there will be young dancers who will suddenly realise they want to keep the tradition true.

- The Bolshoi Ballet is relaying The Pharaoh's Daughter live to UK cinemas on Sunday 25 November via Picturehouses

- The Bolshoi Ballet performs The Pharaoh's Daughter at the Bolshoi Theatre, Moscow from 22 to 25 November

Who's Who in the Back-to-Base Movement

Pierre Lacotte (originally of Paris Opera Ballet): Romantic ballet specialist and choreographer, who recreated from available texts Taglioni's 1832 La Sylphide (Paris Opera Ballet, 1972), Saint-Léon's 1870 Coppélia (Paris, 1973), Saint-Léon's 1844 Vivandière pas de six (Paris, 1976), Taglioni's The Fairy Lake (Berlin Opera Ballet, 1995), Petipa/Ivanov's Swan Lake (Ballet de Nancy, 1998), Petipa's The Pharaoh's Daughter (Bolshoi, 2000), Mazillier/Petipa's 1860 Paquita (Paris, 2001), Perrot's 1843 Ondine (Mariinsky, 2006).

Sergei Vikharev (originally of the Mariinsky Theatre): Petipa specialist and Stepanov notation reader, who (assisted by Pavel Gershenzon) restored "authentic" stagings of Petipa's The Sleeping Beauty (Mariinsky, 1999), La Bayadère (Mariinsky, 2002), Coppelia (Novosibirsk Ballet 2001 and Bolshoi Ballet 2009), The Awakening of Flora (Mariinsky 2007), Coppelia (Bolshoi 2009), Raymonda (La Scala Milan, 2011), and Fokine's Petrushka (1920 version at Mariinsky 2000, Bolshoi 2010) and Carnaval (1910 version, Mariinsky 2008)

Douglas Fullington, US early music specialist and Stepanov notation reader: assisted Lacotte's recreation of The Pharaoh's Daughter (Bolshoi 2000); recreated Petipa's Le Corsaire ("Jardin Animé" scene for Pacific Northwest Ballet School 2004, the whole ballet for Bavarian State Ballet 2006); recreated dances from Petipa's Raymonda and The Awakening of Flora (Pacific Northwest Ballet School 2007); recreated the final Petipa production of Giselle (Pacific Northwest Ballet 2011) and the 1895 version of Swan Lake Act 3 (Pacific Northwest Ballet)

Yuri Burlaka (director of the Bolshoi Ballet): scholar and notation reader who, with Alexei Ratmansky, reconstructed Petipa's Le Corsaire (Bolshoi 2007); recreated from Stepanov notation Petipa's Paquita Grand Pas (Bolshoi 2008); with Vasily Medvedev recreated Petipa's Esmeralda (Bolshoi 2009)

Alexei Ratmansky (ex-director of the Bolshoi Ballet): choreographer who with Burlaka, recreated, with some original passages, Petipa's Le Corsaire (Bolshoi 2007); rechoreographed, with some original passages, Vainonen's The Flames of Paris (Bolshoi 2008)

Isabelle Fokine: granddaughter of Michel Fokine, heir and stager of his ballets Petrushka, Sheherazade and The Dying Swan at the Mariinsky from the mid-1990s, despite disputes about her authority and ownership

Ann Hutchinson Guest: dance notation expert and historian who assisted Mary Skeaping's restaging of Petipa's original The Sleeping Beauty (American Ballet Theatre 1976); restored from Nijinsky's notation his L'Après-midi d'un faune (Royal Ballet 2000)

Mary Skeaping: former Pavlova dancer and Sadler's Wells ballet mistress who researched and restaged Perrot's 1841 Giselle (London Festival Ballet, 1971); restaged from dance notations, assisted by Ann Hutchinson Guest, Petipa's The Sleeping Beauty (American Ballet Theatre 1976)

Millicent Hodson and Kenneth Archer: professors who created from photographs, drawings and writings an impression of Nijinsky's 1913 The Rite of Spring (Joffrey Ballet, 1987 and Mariinsky 2003)

Watch Zakharova, Filin and the Bolshoi Ballet in the closing scene of Lacotte's The Pharaoh's Daughter

Add comment