Petrushka/ Song of a Wayfarer/ Raymonda, English National Ballet, London Coliseum | reviews, news & interviews

Petrushka/ Song of a Wayfarer/ Raymonda, English National Ballet, London Coliseum

Petrushka/ Song of a Wayfarer/ Raymonda, English National Ballet, London Coliseum

Tribute to Nureyev is a richly entertaining evening

A magical folktale, a male duet, a classical jewel-box - programmes like this should be a rich part of the warp and weft of a ballet company, a night of rich interest and variety, stimulating dancers with challenges to their grace and storytelling skills. That it comes as the briefest glimpse in English National Ballet’s year is truly a pity, especially as it pays tribute to that superlative catalyst in ballet, Rudolf Nureyev.

As a legend he almost instinctively attracts the adjective “blinding”, so impossible an act to follow was he as a stage creature, particularly for the men - but in fact “illuminating” is much the more apt word. Nureyev’s impact was not to blind and limit, but to light up and show new paths - how sensual dancing is, how exciting classical ballet’s technical and physical challenges are, how powerful character storytelling can be, and how the fine art of dance expresses more than any of the verbal arts those strivings and anxieties that can’t be told in public, but which drive all of us on.

If you want an indication of this Russian emigrant’s motives and influence look no further than comparison between this ENB programme and what the Bolshoi Ballet are offering over the next three weeks at Covent Garden - over there the big party-processed Soviet versions of classics, the world that Nureyev escaped, and over here dances that he preferred, dances that look back to the most original geniuses in ballet, Petipa, Fokine, the voices the Soviets overrode.

Nureyev loved dancing Petrushka, if with very mixed success, and it is a wonderful excuse to see it back on stage, the freshest and most vivid of the Ballets Russes folktales, telling a charmingly chilly little tale of the puppetmaster whose creations seem to come alive and plunge us into a scary new world of secret emotions.

Nureyev loved dancing Petrushka, if with very mixed success, and it is a wonderful excuse to see it back on stage, the freshest and most vivid of the Ballets Russes folktales, telling a charmingly chilly little tale of the puppetmaster whose creations seem to come alive and plunge us into a scary new world of secret emotions.

Petrushka is the floppy, cotton-handed pierrot whose heart beats for the porcelain, glassy-eyed Ballerina doll, but she as if by clockwork heads for the brusque, bullying Moor whose brain is only big enough to understand his own entitlement to be number 1. (Pictured right, Nancy Osbaldeston's Ballerina, Fabian Reimair's Petrushka)

While there remain continual disagreements about what is "original" Fokine choreography (last week's Russian Seasons so-called Fokine at this venue was hollowest fake) the impression of Petrushka remains eyecatchingly interesting.

The picturesquely dressed crowds in the street are never one mass, the individuals are picked out deftly by Fokine's staging and Stravinsky's music: vignettes only seconds long focus our eyes briefly - like a TV camera roaming for close-ups - on buskers, drunken oafs, off-duty nursemaids, a man with a bear. They laugh, flirt, rollick, have contretemps with a sheriff over their right to occupy the pavement - it has nothing whatsoever to do with classical ballet, everything to do with life, yesterday’s life, today’s life. And who should ever say that their life is more significant than that of the three puppets, notably Petrushka?

In the middle part we suddenly lose the “outside” view of us looking at the public looking at the shabby little theatre - we are plunged with Petrushka inside his black, empty, deprived world, a slave without liberty, raging impotently against his master and his own handicaps. As is the way in folktales, he gets his revenge only after his death: which is yet another sinister metaphor rather too close to contemporary life than it ought to be.

ENB were generously lent the fabulous costumes and sets by Birmingham Royal Ballet, reproductions of the 1911 designs of Diaghilev’s wizard of folklore Alexandre Benois. How those black demons do fly in the sky! How scarily long the Charlatan’s beard is, how perfect are the painted cheeks and eyebrows on the Ballerina, how exotic and vain the Moor's accoutrements (pictured left, Shevelle Dynott with Osbaldeston).

ENB were generously lent the fabulous costumes and sets by Birmingham Royal Ballet, reproductions of the 1911 designs of Diaghilev’s wizard of folklore Alexandre Benois. How those black demons do fly in the sky! How scarily long the Charlatan’s beard is, how perfect are the painted cheeks and eyebrows on the Ballerina, how exotic and vain the Moor's accoutrements (pictured left, Shevelle Dynott with Osbaldeston).

A responsive company performance, played in lively fashion by the ENB orchestra under Gavin Sutherland, with Fabian Reimair’s Petrushka almost conquering a slightly too robust physical approach with the pathos of his mobile, expressive face and the submissive dip of his neck. Nancy Osbaldeston is the most perfectly glassy of Ballerinas and the mesmerising Charlatan (the puppetmaster) turned out, unsurprisingly, to be James Streeter, who constantly amazes me by his vibrant stage presence and narrative charisma. He also turned out to be the zesty, babyfaced Hungarian leading man in Raymonda who I couldn’t stop watching, even if his feet flap rather than beat.

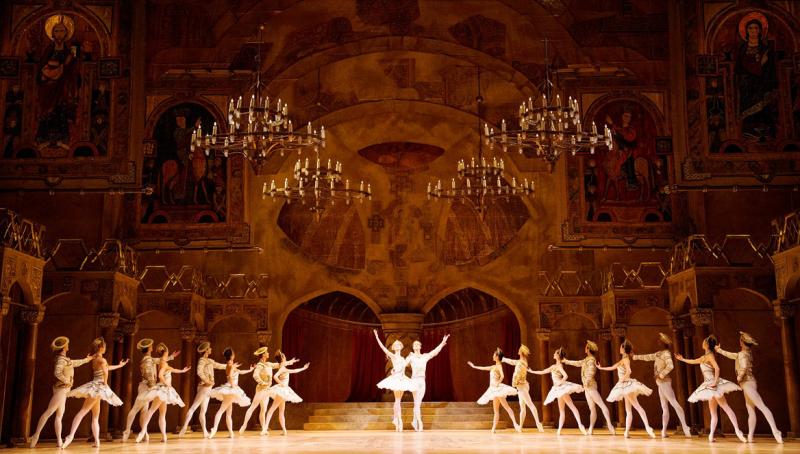

The stage fills with chandeliers and rich white brocades and diamonds, the dancing is a mighty royal party

Character-playing was as much an imperative in Nureyev’s greatness as his classical energy; it was his relish of all the variety of the stage that imbued his dancing with this unforgettable presence, and Streeter's enjoyment is as much evidence of the eclecticism of ballet as the grand pleasure taken in the glittering classic Raymonda by Daria Klimentová and Vadim Muntagirov and company. I admire the sweet poignancy of this partnership between a woman in her forties and a youth in his twenties every time I see it; Klimentová was a longtime useful ballerina until by chance she was put with a callow young Russian by previous director Wayne Eagling. With that lightning that only rarely strikes a partnership, they have become dazzling together, and if I saw them do nothing ever again after Raymonda it would be the right memory.

Klimentová is a fount of joy, her smile of beguiling sweetness, her precise grace spiced by a Czech spirit swaying in the delectably Hungarian-inflected music of Glazunov and some of Petipa’s most jewelled classical choreography, embellished most tastefully by Nureyev himself. The stage fills with chandeliers, palatial luxury and rich white brocades, the dancing is a mighty royal party, but tougher on ENB's men than the women, which is faintly concerning given the prospect of the pirate romp Le Corsaire this autumn.

Klimentová is a fount of joy, her smile of beguiling sweetness, her precise grace spiced by a Czech spirit swaying in the delectably Hungarian-inflected music of Glazunov and some of Petipa’s most jewelled classical choreography, embellished most tastefully by Nureyev himself. The stage fills with chandeliers, palatial luxury and rich white brocades, the dancing is a mighty royal party, but tougher on ENB's men than the women, which is faintly concerning given the prospect of the pirate romp Le Corsaire this autumn.

Between these two demanding old treasures a contemporary work created for Nureyev by Maurice Béjart, the Frenchman whose better work so rarely reaches our shores. By repute the master of grandiosity, In Song of a Wayfarer he made a male duet so pared of excess that you see how prim and modest a step-maker he really is. Set to Mahler’s song cycle, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, it’s a male duet that purports to show a man’s existential journey, accompanied by another man who one supposes to be his guru, teacher, mentor, angel.

The work certainly has some echoes of Kenneth MacMillan’s much richer and more resonant Mahler ballet Song of the Earth - richer because MacMillan used two men and a woman to create a poignant range of different relationships and suggestions about their roles in each other’s thoughts, while here Béjart can’t find sufficient character in his smoothly lyrical choreography for the two men to raise it above a nice display of male grace. He fully presents the two men face-on to the audience with too much openness of the body, they rarely use the contrapposto possibilities that greater choreographers (such as Petipa of course, or Ashton, or Robbins) use to tease, hide, reveal, hint at unspoken things. Tears do not prick the eyes as the man-boy is led out into the dark by his double - it has all been too obvious.

The work certainly has some echoes of Kenneth MacMillan’s much richer and more resonant Mahler ballet Song of the Earth - richer because MacMillan used two men and a woman to create a poignant range of different relationships and suggestions about their roles in each other’s thoughts, while here Béjart can’t find sufficient character in his smoothly lyrical choreography for the two men to raise it above a nice display of male grace. He fully presents the two men face-on to the audience with too much openness of the body, they rarely use the contrapposto possibilities that greater choreographers (such as Petipa of course, or Ashton, or Robbins) use to tease, hide, reveal, hint at unspoken things. Tears do not prick the eyes as the man-boy is led out into the dark by his double - it has all been too obvious.

But Vadim Muntagirov remains so joyously effortless in his boyish classical line and flow that he could dance the Yellow Pages and it would be as interesting. The too impassive Esteban Berlanga couldn’t match Muntagirov’s grace (who could?) and did not use this difference to bring out any other inflections that could stimulate life into the men's relationship (the two dancers pictured above). However, given a thoughtful and telling musical performance by the baritone Nicholas Lester and the orchestra, the pallidness of the choreography mattered less than it might. My stars are for Petrushka and Raymonda - and for the flautist and cor anglais players in them, each with an earworm of a tune, and making the most of it.

- English National Ballet dance A Tribute to Rudolf Nureyev at the London Coliseum today and tomorrow

- ENB's Le Corsaire tour opens 17 October in Milton Keynes, and tours till February 2014

Watch Noëlla Pontois dance Raymonda's solo in Nureyev's Paris Opera Ballet production

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Dance

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

How to be a Dancer in 72,000 Easy Lessons, Teaċ Daṁsa review - a riveting account of a life in dance

Michael Keegan-Dolan's unique hybrid of physical theatre and comic monologue

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

A Single Man, Linbury Theatre review - an anatomy of melancholy, with breaks in the clouds

Ed Watson and Jonathan Goddard are extraordinary in Jonathan Watkins' dance theatre adaptation of Isherwood's novel

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Peaky Blinders: The Redemption of Thomas Shelby, Rambert, Sadler's Wells review - exciting dancing, if you can see it

Six TV series reduced to 100 minutes' dance time doesn't quite compute

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Giselle, National Ballet of Japan review - return of a classic, refreshed and impeccably danced

First visit by Miyako Yoshida's company leaves you wanting more

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

Quadrophenia, Sadler's Wells review - missed opportunity to give new stage life to a Who classic

The brilliant cast need a tighter score and a stronger narrative

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

The Midnight Bell, Sadler's Wells review - a first reprise for one of Matthew Bourne's most compelling shows to date

The after-hours lives of the sad and lonely are drawn with compassion, originality and skill

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

Ballet to Broadway: Wheeldon Works, Royal Ballet review - the impressive range and reach of Christopher Wheeldon's craft

The title says it: as dancemaker, as creative magnet, the man clearly works his socks off

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

The Forsythe Programme, English National Ballet review - brains, beauty and bravura

Once again the veteran choreographer and maverick William Forsythe raises ENB's game

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Sad Book, Hackney Empire review - What we feel, what we show, and the many ways we deal with sadness

A book about navigating grief feeds into unusual and compelling dance theatre

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Balanchine: Three Signature Works, Royal Ballet review - exuberant, joyful, exhilarating

A triumphant triple bill

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet review - Shakespeare without the words, with music to die for

Kenneth MacMillan's first and best-loved masterpiece turns 60

Add comment