William Forsythe's position as the most articulate, fascinating, provocative ballet choreographer of the past 25 years is demonstrated by the Royal Ballet of Flanders' brief visit to Sadler's Wells for three nights with his epic, maddening, engrossing creation, Artifact. The cutting edge of theatre and ballet at its premiere in 1984, it is a four-act ballet, no less, that pays homage to the early court spectacles out of which ballet was born, and the superb physical elegance into which classical ballet then evolved.

I append below Forsythe's own explanation to me of what it's about, but in terms of what you see - Sadler's Wells strips back its stage to a black brick box, like a vacant warehouse waiting to be lit and filled, into which step three odd characters beamed in from past eras and a troupe of modern ballet dancers.

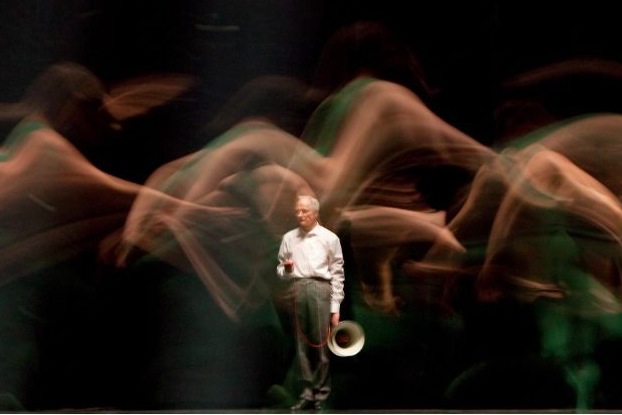

Two of them are speaking parts. The "Character in Historical Costume" is a woman out of her wits, or out of her own time period, or dreaming, urging herself (or us) to "step inside" again and again (pictured left, Kate Strong). A "Character with a Megaphone" is an old man who looks like a gardener, murmuring through his megaphone suggestive ideas for word association, rocks, sand, dust (pictured below, Nicholas Champion). "The Other Person" is a slinky dusty creature prowling barefooted through the action, who, if you are of a fanciful turn of mind, you might imagine to represent a primitive movement idea learning to be born. Or you might just think, to hell with all this clever-clever philosophising, shut up and dance.

Two of them are speaking parts. The "Character in Historical Costume" is a woman out of her wits, or out of her own time period, or dreaming, urging herself (or us) to "step inside" again and again (pictured left, Kate Strong). A "Character with a Megaphone" is an old man who looks like a gardener, murmuring through his megaphone suggestive ideas for word association, rocks, sand, dust (pictured below, Nicholas Champion). "The Other Person" is a slinky dusty creature prowling barefooted through the action, who, if you are of a fanciful turn of mind, you might imagine to represent a primitive movement idea learning to be born. Or you might just think, to hell with all this clever-clever philosophising, shut up and dance.

However, that would be to miss much of the fun. "Welcome to what you think you see," says the regal lady at one point. Games are being played throughout, with Bach's Chaconne, which is constructed, reconstructed and deconstructed - for piano, for violin, chopped up, run backwards and overlapped - and with all sorts of tricks and ideas from balletic eras. Given that the huge corps de ballet are such a magisterial feature of the piece, you aren't shortchanged for the ballet itself either - no one that I've seen since can match Forsythe's Eighties ballets for voluptuous attack and strictness of form. I weep with joy just to see the rigour of it in these starved times.

In their dark second-skin leotards and semi-opaque tights they hit a perfect equilibrium between athleticism and sensuous expression. There's a sublimely simple ensemble built as if out of classroom exercises that suddenly recaptures the poetry of the 19th-century Kingdom of the Shades from the classical ballet La Bayadère, another that echoes a Balanchine Symphony in C finale, yet another that seems to hint at the inchoate militaristic terror of the Wilis' underworld in Giselle, in which The Other Person plays a haunting, perplexing part (pictured below, Eva Dewaele). I think the second part of the four, a ravishing ensemble for two couples and the corps de ballet - with the Chaconne now played in full by that most human of violinists, Nathan Milstein - may have to enter my list of Desert Island Dance.

In their dark second-skin leotards and semi-opaque tights they hit a perfect equilibrium between athleticism and sensuous expression. There's a sublimely simple ensemble built as if out of classroom exercises that suddenly recaptures the poetry of the 19th-century Kingdom of the Shades from the classical ballet La Bayadère, another that echoes a Balanchine Symphony in C finale, yet another that seems to hint at the inchoate militaristic terror of the Wilis' underworld in Giselle, in which The Other Person plays a haunting, perplexing part (pictured below, Eva Dewaele). I think the second part of the four, a ravishing ensemble for two couples and the corps de ballet - with the Chaconne now played in full by that most human of violinists, Nathan Milstein - may have to enter my list of Desert Island Dance.

"Artifact" means a thing made of art, and this is precisely a ballet about ballet. So if you already love and know some ballet (and have a certain threshold of tolerance for a choreographer's theatrical idiosyncrasies) you may be gladdened, as I am, to see the amusing and often poignant homages Forsythe deploys, alighting swiftly on this or that reference in the library of ballet. If you don't know anything about ballet, you will be amazed by the luscious vigour of the choreography and the élan of the Royal Ballet of Flanders' performance. If you want to revel in the sheer sophistication of theatrical stagecraft, go and look at that visual space, that lighting, that barely perceptible trelliswork of spotlights rising out of the pit, meshing across the front of the softly muzzy air, the sharp ways that Forsythe drops the curtain mid-action, like an eyelid casting doubt on the view, or just saying, I'm tired, give me something else now.

"Artifact" means a thing made of art, and this is precisely a ballet about ballet. So if you already love and know some ballet (and have a certain threshold of tolerance for a choreographer's theatrical idiosyncrasies) you may be gladdened, as I am, to see the amusing and often poignant homages Forsythe deploys, alighting swiftly on this or that reference in the library of ballet. If you don't know anything about ballet, you will be amazed by the luscious vigour of the choreography and the élan of the Royal Ballet of Flanders' performance. If you want to revel in the sheer sophistication of theatrical stagecraft, go and look at that visual space, that lighting, that barely perceptible trelliswork of spotlights rising out of the pit, meshing across the front of the softly muzzy air, the sharp ways that Forsythe drops the curtain mid-action, like an eyelid casting doubt on the view, or just saying, I'm tired, give me something else now.

The entire creative kudos for the show goes to Forsythe himself, as choreographer, director, writer, designer and lighting man, which demonstrates just what a good mind the man has. It's a piece that should claim classic status in the future, a landmark in its theatrical and balletic range. But apart from Forsythe's own now-dissolved Frankfurt Ballet, the Royal Ballet of Flanders have been one of only two other companies he's fully trusted with his work, directed by his former assistant Kathryn Bennetts. The passion and focused intent of last night's performance speaks highly of her abilities as she leaves this troupe this year, but it leaves also the question of just who will be there to keep a protean creation of modern ballet theatre like Artifact alive. Too challenging for the mainstream, but so much more alive than the mainstream.

Could English National Ballet take up Forsythe under its next director Tamara Rojo? Now there's a thought.

In October 2001 I visited Ballett Frankfurt’s base in the Oper Frankfurt, on the north bank of the Main river, to find out from Forsythe about the two full-length ballet productions he was about to show in London, Artifact and Eidos: Telos. I asked him what Artifact was.

Above: the Royal Balelt of Flanders in Forsythe's Artifact (image © Johan Persson)

WILLIAM FORSYTHE: Artifact is a narrative evening-length piece which is patterned on the baroque ballet of let’s say the 1600s, like that done for Catherine de Medici at her wedding - which was a form of politique, put there to appease warring factions of Catholics and Protestants in France. They were designed as demonstrations of harmony, but at the same time there was a certain irony since this was the noble class reacting to the absolute monarchy being solidified in its position. Artifact is a hypothetical reconstruction of something in this period, but with the ideology in place - not the steps, but the ideology. I’ve worked on it for a long long time, and read new pieces of scholarship about the dance history of this time, and amended the ballet to take account of it. It’s been a very interesting project (he smiles) - classical dancing organised around a hypothetical reconstruction based upon an ideological reading of the historical background.

ISMENE BROWN: So is there a message coming out of it?

WF: That history is more complex than you think. Especially the history of aesthetics. The aesthetics of ballet are there for very complex reasons, not just to entertain or please, it was more designed as political events. And I was so shocked to find that out! I had intuited one thing by practising it, because the practice of ballet does inform you about its history in one sense - but it’s hard to formulate so I went back and tried to read about the cradle of ballet-dancing, and slowly found out the basis of these formations. And it was political, not necessarily to entertain. These burlesques, for example, could be a kind of protest. And the ideologies of the 18th century were solidified with the neo-Platonism that governed political thinking and aesthetic thinking hardened into a kind of system - very French.

So I just tried to create in the tradition of what ballet has become, to create a piece about what it was. It’s almost like a mirror. It’s changed, and as from that point how can I mirror it, in the light of what we know now?

IB: You mean that the King employed the dancers to demonstrate his power, but that once on stage they then took on the power to say something different?

WF: Exactly. And it was done in such a fashion that the King himself was in the performance and therefore became the subject of it. So it was a kind of meta-reflexive event.

IB: And the king appears in Artifact?

WF: Yes, and it’s very interesting to see where, to whom, the revolution is assigned - the revolution of form. Because they had to do it within the codes of politique of that time. You had to subvert it by its own means, which was politeness. It’s an interesting project, I still don’t tire of it. i’ve been reading a book by Mark Franko, a brilliant book: The Body as Text, Ideologies of the Baroque Body. An amazing book, it pulls everything together. It’s hard to find.

IB: Am I right in thinking that your ballet in the middle somewhat elevated (made for Paris Opera Ballet) was also intended as a court entertainment?

WF: Yes, but placing Rudolf Nureyev in the position of the King. I originally called it Impressing the Tsar. I did it as a joke to see how Rudolf would react, and of course he loved it and was furious when I took the title away! The irony is also, that Rudolf being Rudolf, he thought the new title was sexual, but I said, "No, Rudolf, it’s about the two cherries hanging over the dancers." [He stares up into the ceiling, as the dancers do at the start of it.] The dancers start, staring up at the two cherries.

The aesthetics of ballet I see as the result of politics, which is very interesting indeed. The why, not just the what

IB: OK, so what makes a republican, an American, living in the republic of Germany, get so interested into this monarchical aspect of ballet, when you are supposed to be the 21st-century modernist?

WF: Of course it’s not ideological - it’s a complex political subject, I don’t see it as an exclusively aesthetic subject. The aesthetics of ballet I see as the result of politics, which is very interesting indeed. The why, not just the what. I’m having an interview in England with an expert on the evolution of épaulement, because I have big questions about when that was institutionalised. Exactly when that happened. Because you can place it in a social context, but unless you know what’s going on in the rest of the world you can’t understand the event.

IB: It’s so subversive, isn’t it? Epaulement subverts ballet rules.

WF: Oh, it’s the best. I wonder what ballet was before it had épaulement. Because we have 1620 the Royal Academy, boom, in place. But when did this complex counter-taught mechanics come along?

IB: Maybe when the first 16-year-old rosy-cheeked girl in the dancing company caught the eye of the king and blushed and looked away.

WF: But when was it built into the training?

IB: Perhaps the king said to to balletmaster, "I like what that girl did, make sure they all do it."

WF: I’m going to find out! I want to see if anyone has done scholarship on it, so we can pin it down.

IB: The title of Artifact implies something solid, crisp, edged, complete, the opposite of your evolving project.

WF: Yes, but that’s the nature of dancing. The question of whether there is such a thing as a dance artifact. It’s an oxymoronic situation. Could there be such a thing as a ballet artifact? You’re probably the first person who’s queried the title. I would go further, and say it’s actually a trap, a bit of a lure.

I say to the dancers, you must make a discourse when you dance. You have to make a re-affirmation of ballet and yet at the same time bring into question how ballet is danced

IB: This version we’re seeing now has changed a lot since we saw it in London three years ago [1998].

WF: Yes, that was Dutch National. I’ve still been changing it last week. Now you’re really going to see it. God bless them, but they are very much a ballet company. And whereas it can be done with a “Ballet Company”, it’s got really to be done by people who have a discursive relationship with what they are dancing, rather than just “performing” it. I say to the dancers, you must make a discourse when you dance. You have to make a re-affirmation of ballet and yet at the same time bring into question how ballet is danced.

IB: Which brings up the question of how ballet companies can actually perform your dances.

WF: Very difficult. The training is very different - mentally. Ideologically it’s different, that’s the problem. Or mentally, if you wish. The psychological restrictions, or constraints of institutionalisation of ballet. What’s the difference is between obedience and rigour? That’s the deciding issue

IB: Essentially obedience from an early age.

WF: Yes, it is. it’s a corps, it’s like an army corps.

IB: But you needed that...

WF: You thought.

IB: I mean, to do your work... how dare I say it? but...

WF: Oh, go ahead, dare!

IB: I mean, I don’t think you could have done what you have done with classical ballet unless you had started from the basis of a bloody good classical training, and bloody well trained classical dancing.

WF: What’s the difference is between obedience and rigour? That’s the deciding issue. Rigour is what I’m going for - how and why these things are employed. Because what are you saying? You have to know the difference between two small variants of one thing, and if you don’t know that difference, every detail, then you cannot be discursive, you cannot talk about what you do. You are not expert in what you are doing, if you just do what you are told.

And there are so many different schools of it. I see the girls all moving their heads in Artifact, and you can see the slight differences in their heads that show their slightly different schoolings. it’s quite difficult to decide exactly which coordinates to go for. Because tendus are tendus, but where the real schooling and the real discourse comes out is in the arms and head.

IB: Whose do you like most? Who is most free?

WF: To a point, the Americans move extraordinarily freely. The French and... in some cases the Russians - basically the Kirov, who are more French than, certainly, the Bolshoi who hold their arm positions up here [he stretches it up high and away]. Although Nina Ananiashvili is also always out there, which is more to do with her body, I think.

But I think the French are extraordinary. After Rudolf worked with them, they have become consummate global ambassadors for the art form. They can adapt themselves to any style. Look at [Paris Opera Ballet's ballerina] Elisabeth Platel - she can be hyper-romantic, like some hole into the past, quite thrilling. It’s not a case of her being conservative, but of her conserving an attitude of the body that relates to that body politic of its time - it’s fascinating, not old-fashioned. A line, a way to see into history.

You do have to love it, and to really love it you have practise it every stinking day, in order to decide why you love it

IB: I’m so glad you say that, because a lot of people say classical ballet is old, out of date, lost its time. And actually to have a historical perspective on anything brings it alive. It would be like saying we are not interested in the Pharaohs’ tombs because we don’t care for their social structure.

WF: (he laughs heartily). That’s good. But I’d say that something like Artifact does revive interest. You find the most diverse people going, "Oh, ballet's very interesting." But you do have to love it, and to really love it you have to practise it every stinking day, in order to decide why you love it, and also learn what you find not good about it. Like the militaristic underpinnings of it.

IB: Or the anti-feminist side of it too. Such a tedious argument.

WF: Yes, you can only say, "That was the way things were handled then." If someone doesn’t want to work that way now, that’s perfectly up to them.

IB: It’s out of historical structures that you get works of art.

WF: And they are art-historical - they come from their time only. And they also show why things should be different now.

- The Royal Ballet of Flanders perform Artifact at Sadler's Wells Theatre, London tonight and tomorrow; it then tours to Birmingham Hippodrome in the International Dance Festival Birmingham on 25 & 26 April

- See the full Sadler's Wells 2012 season listing here

Add comment