theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Ilan Volkov | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Ilan Volkov

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Ilan Volkov

The conductor on his career, contemporary music and coughing during concerts

Relentlessly energetic, opinionated, and never less than passionate about music-making, Ilan Volkov is a close as you get to a prodigy in the world of conducting. Appointed as Young Conductor in association with the Northern Sinfonia at just 19, at 28 Volkov became the youngest ever chief conductor of a BBC orchestra, and almost 10 years later still continues his relationship with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra as their Principal Guest Conductor.

It’s typical of Volkov that one of the projects closest to his heart is the tiny alternative classical venue Levontin 7 that he has set up in Tel Aviv with two friends. Comprising just “a basement and a bar”, it has become both a laboratory and an incubator for the kind of experimental performance scenarios and programming the conductor is increasingly championing in his work with orchestras. The latest fruit of these experiments is the Tectonics Festival Volkov debuted in Reykjavik this spring, and which will continue as an annual event not only in Iceland but in Glasgow and ultimately internationally, as Volkov builds new partnerships with cities and their orchestras.

It's not my job to help listeners, it's to show them what's out there

As befits the conductor who once confessed that he’d like to spend the next 20 years doing only pieces that are new to him, Tectonics perches at the extreme edge of classical concert-hall repertoire. Focusing on the experimental music of the past half-century, Volkov’s programmes champion the orchestral repertoire of composers such as John Cage who are best known to a tiny minority of specialists for a tiny proportion of their smaller works. In each city it visits Tectonics also takes on a distinctively local colour, celebrating the work of national composers, particularly living ones, and involving young musicians and smaller ensemble projects alongside large-scale events.

Taking a night off from conducting, Volkov appears next week at King’s Place both as violinist with his improvising trio Mines, and also as curator of an evening of new music that will include works by Morton Feldman and Christian Wolff, as well as fellow performers John Tilbury and Volkov’s own partner Maya Dunietz. It’s a bold and irreverent approach to programming typical of the conductor, and one that increasingly spills over into his orchestral work. Volkov talks to theartsdesk about this love of experimental music, his inner geek, and why coughing during concerts can be a good thing.

ALEXANDRA COGHLAN: Your new festival is called Tectonics – a name with some quite violent, destructive resonances. Was that intentional?

ILAN VOLKOV: I think we need to be a bit destructive in our thinking about the orchestra as a musical structure in order to renew it. An earthquake is not only destructive, it’s a force for renewal and change, a radical shift that happens both across large spans of time and in a moment. I’m interested in new art-forms, the most radical artists. It’s interesting for me to work with people who are changing the scene. We’re taking a trip with this festival that refuses to accept the basic ground rules of classical music; it’s about the clash between the old world and the new world, and how an orchestra which is a very beautiful, old-fashioned organisation and machine that still has so much to offer, can develop.

Do you think Iceland as a nation and the Iceland Symphony Orchestra are particularly receptive to these innovations?

This is an amazing moment in the history of Iceland because of the huge difficulties they are experiencing. They had an earthquake, not physically, but the whole country was jolted, and they are now rethinking everything. They are criticising themselves, and thinking about why the crash happened, so this is a really interesting moment to make art that is addressing those same questions, that is rethinking why we do things, how we deal with notation, instruments, and even the body of the performer.

The festival places a lot of emphasis on local Icelandic performers and composers, as well as young musicians. What role do they play within Tectonics?

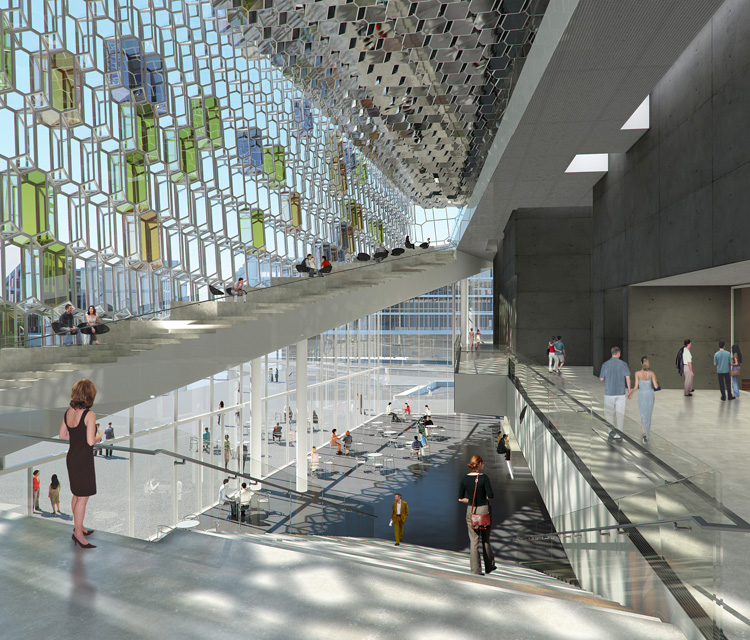

The ISO have this incredible new home, the Harpa concert hall, but if they don’t invite people in then they will never come. For me it’s very important that the orchestra understand that they have a responsibility, not only in the youth projects that they do, but also to local composers and young people who are not directly involved in classical performance. If you play music on the streets you don’t have any responsibility to anyone, you just have to survive, but if you have a home like Harpa (pictured above right) then you have to share it; you have to give it away. Why should people care about what we do here if we don’t include them, if we don’t talk to them, explain to them? For me using local artists is a hugely important part of the festival. There is talent here enough, so why should I waste so much money on flights to bring in artists from outside, when I could use it to commission new works here? That’s the same attitude I will have in Glasgow, and wherever this festival will find partners. Depending on which orchestras or ensembles I work with the festival could be huge or very small, but it must always be challenging and interesting. I’m not just interested in grandiose projects like this with three or four concert halls and hundreds of performers.

The ISO have this incredible new home, the Harpa concert hall, but if they don’t invite people in then they will never come. For me it’s very important that the orchestra understand that they have a responsibility, not only in the youth projects that they do, but also to local composers and young people who are not directly involved in classical performance. If you play music on the streets you don’t have any responsibility to anyone, you just have to survive, but if you have a home like Harpa (pictured above right) then you have to share it; you have to give it away. Why should people care about what we do here if we don’t include them, if we don’t talk to them, explain to them? For me using local artists is a hugely important part of the festival. There is talent here enough, so why should I waste so much money on flights to bring in artists from outside, when I could use it to commission new works here? That’s the same attitude I will have in Glasgow, and wherever this festival will find partners. Depending on which orchestras or ensembles I work with the festival could be huge or very small, but it must always be challenging and interesting. I’m not just interested in grandiose projects like this with three or four concert halls and hundreds of performers.

Next year will see not only a new Tectonics programme in Reykjavik, but also one in Glasgow…

Yes, we have commissions in place, and the BBC are very much behind the project. The 2013 festival in Glasgow will have a big concentration on British experimentalism, involving Frank Denyer and other composers who are represented in small, niche circles but usually are not played or commissioned by symphony orchestras. I want to expand the horizons of what an orchestra does and to make people aware of the extremes of that particular scene. For example, very few people know about John Cage’s orchestral works. Between 1985 and 1991 he wrote around 70 orchestral pieces, but audiences just don’t hear this music, and therefore they don’t know its value, or understand its weaknesses or strengths.

Cage is a recurring theme in your programming. Where did this interest come from?

I was never taught about Cage at the Academy, they didn’t show me the scores or teach me how to perform them. It’s only in the last few years that I have learned. It’s a whole new field of music for me, and as far as I’m concerned it’s crucial to expanding the repertoire. Cage’s orchestral pieces could be programmed and make sense played alongside Bruckner – it’s beautiful and incredibly interesting music to perform – but they’re just not being played.

As part of this year’s Tectonics you directed the ISO in a full orchestral improvisation with electric guitarist Oren Ambarchi. What did you hope would emerge from this experiment?

Usually classical musicians look down on improvisation – it’s not structured enough, detailed enough, organised enough. It’s a bit like the relationship between written and oral traditions of literature. But these improvisational works have things which written-out compositions do not. It’s a different way of approaching playing. So when we did the full orchestral improvisation – something I’ve never done before – it is taking this concept to the extreme; it’s real-time composition.

Usually classical musicians look down on improvisation – it’s not structured enough, detailed enough, organised enough. It’s a bit like the relationship between written and oral traditions of literature. But these improvisational works have things which written-out compositions do not. It’s a different way of approaching playing. So when we did the full orchestral improvisation – something I’ve never done before – it is taking this concept to the extreme; it’s real-time composition.

Extremes are exciting, but don’t you worry that you risk alienating audiences?

It’s not my job is to help listeners, it’s to show them what’s out there. But it’s a lot to do with choosing the right pieces, and the circumstances in which you perform the music – how you frame it, light it, price it. This year’s programme for the ISO will incorporate lots of classic symphonic works, but I am always searching for new repertoire that neither the audience nor the orchestra know – repertoire I hope will become contemporary classics.

It’s up to each individual to decide at what point sound becomes music, or music becomes politics

Between ENO’s Klinghoffer and the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra’s residency at the Proms this year, we’re seeing a lot of political issues emerging in London’s classical music scene. What’s your view on the role of politics in music-making?

I am very unhappy with a lot of things in the world. I am unhappy with the situation in Israel – that’s particularly close to my heart – but for me every person needs to decide for himself whether he wants to engage with these issues while he is making music or during his free time though activism. I am more and more aware of the dangers of politics, of being convinced that you are right and not respecting those who disagree with you.

So should politics stop at the concert hall door?

No. Sound is everywhere, and it’s up to each individual to decide at what point sound becomes music, or music becomes politics. If I find a political piece that I think is musically strong and makes a statement then I will perform it, but we’ve heard what politically engaged music can lead to – it can lead to works like Cardew produced towards the end of life, which is obviously not the way to go. Whenever you use music for non-musical ends there is a danger, and there is a general fear in the arts of dealing with the world that we are living in. There are two responses: we either create a world that doesn’t exist or face our own world head on. I like musicians who take risks, but as a performer and curator myself I don’t want to try too consciously to shape the statement that is emerging from the music.

What about more practical models for musical politics like West-Eastern Divan Orchestra?

Teaching is great, but it should be about teaching the people that need teaching, the people who don’t have money, who don’t have access to music. So, although it’s a great project in musical terms, I’m less interested in it than in the work of my friends who are working in Israel and going every day to the West Bank to teach music. They need funding. Music has a healing power which people are gradually discovering, and this is really important not as a political tool for a country to become famous, but as a real tool that can help people. You have to take individual ego out and do something that is valuable. Lots of orchestras take on education projects because of the funding that comes with them, but you need to do it because you want to do it and because you know why you want to do it.

You worked a lot with youth orchestras at the start of your career. Is that something you see continuing?

I think I could do a much better job of it now. I am teaching conducting at Dartington Summer School this year – the first place I ever conducted myself – and will also be conducting the youth orchestra in Israel, so people are beginning to ask me to do this kind of work.

You famously started conducting while still very young yourself. Semyon Bychov has spoken about the the need to earn the right as a young conductor to stand in front of a great orchestra. Do you share that philosophy?

Yes, I would agree. I did start young, but I was very lucky to be working with agents who never pushed too hard. They even advised me occasionally not to do certain things. On one occasion they advised me against doing a high-profile concert with the New York Philharmonic and they were right. I was perhaps 23 or 24, and although I thought I was ready I just wasn’t psychologically. It takes time to learn how to behave as a conductor. It’s not enough to know the music, to feel the music, and to show it beautifully. You also have to know how to communicate. That’s going to take me at least 50 years to get to grips with. It’s a matter of character, and finding within yourself what works. You can’t copy anyone else, you need to find a way to communicate and inspire people that helps them to respect you.

You worked a lot in your early years with Seiji Ozawa (picured right) at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Did his approach have much influence on yours?

You worked a lot in your early years with Seiji Ozawa (picured right) at the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Did his approach have much influence on yours?

He’s very physical as a conductor; he knows the music in his body, knows it inside-out in an amazing way. He breathes the music, and so it’s very easy to play for him, it’s like breathing. Someone like Haitink conducts in a very different way, but is equally easy and natural to follow. These conductors are not forcing themselves upon other people, they are providing a lot of space for the musicians to play. It’s an interesting approach, but not perhaps the modern way. As conductor you are in the number one, but it’s a team, and you need to realise that if the musicians don’t want to play for you it will sound like shit, even if you’ve conducted them amazingly. All the great conductors know that. As a conductor you gradually understand where you need to push, where you need to let go, where you need to ask questions. Sometimes you say too much, sometimes you don’t say enough.

Do you change your approach from orchestra to orchestra?

Sure. I have worked in Japan, Lyon, Germany and Glasgow this season and I had to be different everywhere. You have to be yourself – totally convinced of your ideas about the music. If you are truthful and people can see your dedication, then people will follow you.

Can you explain difference in character between ISO and BBC SSO in terms of sound they make and how they work?

The BBC is an amazing organisation, one I like more and more, because they understand how to produce things. The BBC SSO are not a normal subscription orchestra, which gives you more freedom. They are not afraid of challenges, they know how to get things done, how to record things quickly. We made a lot of records and did a lot of new pieces together. Now when I go back they are an amazing new music orchestra. They can do everything. Here at the ISO it’s a very different setup because the orchestra have been stuck for so long in a terrible space with such small audiences. So now that they have arrived in their new home, Harpa’s huge concert hall, they need to learn how to play in it. It’s the opposite of their old home in acoustic terms. There are amazing things to come from the ISO, but it’s a long term project.

So their orchestral sound is still under construction?

Yes, but they do have a character. It’s very strong – I can feel the energy they have when they play well, that particular quality of sound. I have my geeky qualities and can listen to recordings blind and identify who is playing, but I don’t think it’s important. Great orchestras have to perform many different kind of music, so they are not supposed to produce the same Vienna sound or Philadelphia sound for Mahler, Beethoven, Stravinsky and Stockhausen – that’s not the point. But we all learned from Karajan the opposite approach, which treats all music the same way. As a musician you have to put different masks on yourself; you have the same attitude underneath, but you need to change your Ravel sound from that of Shostakovich. If you can’t change then you can’t perform.

Have you succeeded in getting this flexibility from orchestras?

We tried to do that in Glasgow and yes, I think we succeeded. We tried to do a lot of mixed programming, so we would consciously have to change sound and articulation between pieces. The great thing about English orchestras is that they are chameleons. Maybe what they lack is an old Russian or an old German sound in the strings, but they have their own way and it works. It’s not about particular bowing technique or vibrato but interpretation, and that – I think – is the most interesting thing: tempo, breath, structure, dynamics. Whether you perform Beethoven’s Third Symphony with or without vibrato doesn’t matter, what matters is how you as a conductor express the underlying structure in performance.

You’ve become known for programming collisions between unlikely composers and pieces – Ligeti’s San Francisco Polyphony, Mahler’s Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen. Have any of these worked particularly well and made you think of the music differently?

Yes, there have been occasions when I have suddenly realised something about the music in the moment of performance, during the concert. It’s not something you invent, it’s something you suddenly realise is there – a shift of perception, a moment of pure energy. It often seems to happen at the Proms; even though the audience can’t see the conductor very well in the Royal Albert Hall, there’s something physically happening between the musicians, the conductor and the audience. I have performed very soft music there a few times, and through just one gesture the whole audience was quiet and didn’t cough or move; if you are completely concentrated as a conductor the audience can sense it and respond. As a conductor I don’t think you should be thinking about the audience at all, but your energy reflects back off the orchestra – there’s a mirror effect happening throughout.

But what happens when an audience is struggling to concentrate, or engage?

You’ve said in the past that you’d like to set up your own ensemble to fulfill your much more fluid ideas of how musicians and orchestras should work. Is that something you still want?

I’m not so sure now. I think the Tectonics Festival could fill that space for me, if I do it five or six times a year around the world with different organisations. But the next big job I take on will have to be interesting to me. I want an orchestra that is keen and open to developing, not one that just wants to preserve and protect their legacy. If I find that then I will do it.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment