theartsdesk in Abu Dhabi: The Art of Diplomacy | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Abu Dhabi: The Art of Diplomacy

theartsdesk in Abu Dhabi: The Art of Diplomacy

A young festival brings East and West together in fruitful fusion

You can’t walk down the street in central Abu Dhabi. Not because of any danger or prohibition, but simply because there just aren’t any pavements yet. Look out of any one of the high-rise buildings that dominate the city, and you’ll see a landscape modestly veiled in the dust of construction. Roads, schools, hospitals and inevitably hotels are all emerging from the desert at a rate that renders the city map unrecognisable every six months.

The United Arab Emirates is a country of contradictions. One nation, its seven principalities – Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah and Umm al-Quwain – all retain distinct identities as well as healthy rivalries. Although an ancient land inhabited since 5500 BC, the country is still in its political infancy, with the Emirates only established in 1971. The discovery of oil in the 1960s changed everything, creating a nation suddenly among the very wealthiest, capable of lavish displays of excess, but still founded in the ascetic principles of Islam.

In Saudi Arabia anyone seen with an instrument is liable to find not only it but themselves attacked and broken

Although the capital of the UAE, Abu Dhabi has hitherto been sidelined internationally by the sprawling reputation of neighbouring Dubai. But while Dubai’s development has come faster, targeting the high-profile, high-end consumer market in its projects, Abu Dhabi’s rivalry is growing every year, and taking a noticeably different form. While offering the same material attractions as Dubai – the hotels, malls and beaches – Abu Dhabi is also investing in its development as a cultural destination, a project for which the city’s annual arts festival has been both catalyst and flagship.

A glance through the list of previous festival artists – Anna Netrebko, Maxim Vengerov, the LPO, José Carreras, the Bolshoi Ballet and Orchestra – traces the Abu Dhabi Festival’s growing strength and stature. An early emphasis on classical music has been sustained, but alongside this an increasingly bold programme of performing and visual arts is also developing. Akram Khan's Push, a contemporary dance piece with Russell Maliphant and Sylvie Guillem, was last year’s surprise hit, pointing to an Emirati and expat audience eager for something more challenging than imported cultural bonbons.

The role of music within the festival is particularly interesting, given the traditional reluctance of the Islamic nations to embrace the performing arts. While visual arts and crafts have long flourished both culturally and as commodity (as events such as Art Dubai make clear), theatre and music have historically had a more fraught relationship with social and religious life. A visit to Abu Dhabi’s Beit Al Oud – The House of the Oud – brings this issue to jangling life.

The role of music within the festival is particularly interesting, given the traditional reluctance of the Islamic nations to embrace the performing arts. While visual arts and crafts have long flourished both culturally and as commodity (as events such as Art Dubai make clear), theatre and music have historically had a more fraught relationship with social and religious life. A visit to Abu Dhabi’s Beit Al Oud – The House of the Oud – brings this issue to jangling life.

A musical academy devoted to the oud, the traditional 11-stringed Eastern lute, the Beit Al Oud was founded in 2007 by Iraqi oud virtuoso and composer Naseer Shamma (pictured above), an offshoot from his original school in Cairo and part of a planned network of similar academies across the Arab world. While the voice and history of the oud extends back some 5000 years, like so much else in the UAE the instrument’s role in national culture has only recently begun to be formally developed and acknowledged, with a new and distinctively Emirati school of oud-playing finally emerging.

An aural tradition, oud music has never historically been notated, and it is only under the aegis of the Abu Dhabi Festival that Shamma’s own compositions have just been published – the very first volume of its kind. While visiting the calm, cool house that plays home to Shamma’s school we meet several of his pupils, including the first female oud player to graduate from the Beit Al Oud. Previously based in Cairo she explained the resistance to her chosen profession that she experienced there. And while walking down an Egyptian street with an oud might draw suspicion upon a woman, in Saudi Arabia anyone seen with an instrument is liable to find not only it but themselves attacked and broken.

Viewed in such context, the UAE offers a strikingly liberal and progressive home to Arabic musical culture, and in the hands of Shamma and his teachers the oud is slowly emerging as an icon for a nation still in search of its cultural identity. Emirati performers such as Faisal Al Saari, another of Shamma’s graduates and acclaimed for his virtuosity, represent the beginning of a genuinely homegrown tradition – one however that is already open to cross-cultural dialogue and playful innovation. While Shamma has been known to explore Western classical repertoire, performing Paganinni’s Caprices on the oud as well as Vivaldi’s Mandolin Concerto, for Al Saari it is Western popular music that holds particular appeal, and he regularly includes arrangements of film scores (the theme from The Godfather or James Bond on the oud, anyone?) in his programmes.

While the vernacular tradition found in the musicians of the Beit Al Oud offers particular hope and a template for the development of the Abu Dhabi Festival, the festival’s artistic director Mrs Hoda Al Khamis Kanoo also places great emphasis on its international partnerships. The relationship with the UK is a particularly strong one, and the 2012 festival has seen work from the Royal Opera, Shakespeare’s Globe and the Manchester International Festival transfer to Abu Dhabi. Individual performers and ensembles also visit, their programmes shaped each year by the over-arching festival theme.

The 2012 theme – “Connecting Cultures” – could easily serve as a subtitle for the festival more broadly, celebrating precisely the polyphonic collision of nationalities and cultural influences found in the UAE. Thus when we sat in the gilded theatre of the Emirates Palace Hotel, traditional abayas and dishdashes jostling with slinky Western cocktail dresses, to hear Anoushka Shankar (pictured right) performing music from her new Traveller album, this unusual musical fusion seemed entirely natural and at home.

The 2012 theme – “Connecting Cultures” – could easily serve as a subtitle for the festival more broadly, celebrating precisely the polyphonic collision of nationalities and cultural influences found in the UAE. Thus when we sat in the gilded theatre of the Emirates Palace Hotel, traditional abayas and dishdashes jostling with slinky Western cocktail dresses, to hear Anoushka Shankar (pictured right) performing music from her new Traveller album, this unusual musical fusion seemed entirely natural and at home.

Fusing Indian classical works and techniques with Spanish flamenco music, this repertoire (much of it composed or arranged by Shankar herself) draws attention to that howl of emotional immediacy shared between these two musical cultures. Rhythmic patterning may offer the most obvious musical overlap, but it is the spirit of the two traditions that truly connects here. Shankar is a compelling performer, and framed in the lighting and visual effects of such a space, this was as much theatre as concert. Cumulative waves of modal variation and development circled around her sitar – seemingly an aural echo of the elaborate arabesques of Islamic art found everywhere in the UAE.

Islamic art finds rather more direct echo and derivation in the exhibition commissioned by this year’s festival – Gestures of Light. Iraqi artist Hassan Massoudy is something of an anomaly, having only truly embraced Arabic calligraphy after leaving Baghdad for Paris’s École des Beaux Arts. The result is an art that takes its inspiration from text – not only from the ideas of philosophers, authors and religious leaders, but more significantly from the very shapes of their words. “Everything becomes calligraphy”, Massoudy has said, but more properly it could be said of this exhibition that calligraphy becomes everything.

Islamic art finds rather more direct echo and derivation in the exhibition commissioned by this year’s festival – Gestures of Light. Iraqi artist Hassan Massoudy is something of an anomaly, having only truly embraced Arabic calligraphy after leaving Baghdad for Paris’s École des Beaux Arts. The result is an art that takes its inspiration from text – not only from the ideas of philosophers, authors and religious leaders, but more significantly from the very shapes of their words. “Everything becomes calligraphy”, Massoudy has said, but more properly it could be said of this exhibition that calligraphy becomes everything.

Quotations are written out and then translated into Arabic, the curves and contours of the script exaggerated or distorted to mirror the emotions of the text. A graphic or occasionally geometric image sits above – the final abstract echo, a bright, visual memory of the text where the art both starts and ends. A short quotation from 12th-century Al-Aqili on life, “How sweet it is and yet how bitter,” provokes sweeping aqua arches, textured with jewel-like filigree patternings, while a Khalil Gibran text yields a much more representative image, echoing the colours and shapes of nature found in its text. Shapes spiral and stamp in bold blocks of colours, the water and acrylic-based paintings offering their different personalities to their works. Here are echoes of Apollinaire’s visual poems – texts freed from the restriction of the printed page and lent expressive freedom.

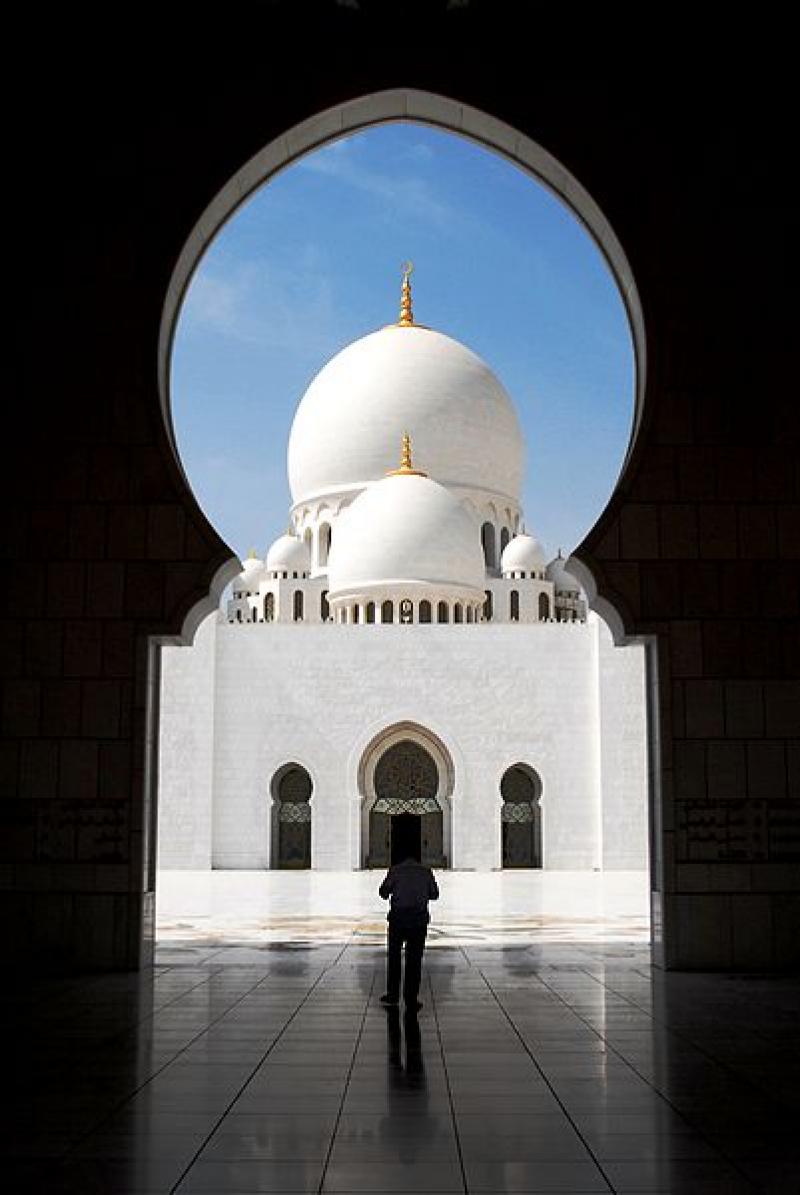

So much of what we see in Massoudy’s art – the shapes and philosophies it returns to repeatedly – gain new resonance after a visit to the Sheikh Zayed Mosque – one of the largest mosques in the world and the ceremonial home of Islam in the UAE. In planning since the 1980s, the mosque was finally completed in 2007 – a delay more than accounted for by the sheer scope and detail of the building. Designed to reflect the international reach of Islam, the mosque housed under the billowing domes of white marble comprises raw building materials and craftsmen from some 20 different nations. A conversation between Mughal and Moorish architectures, the mosque’s restrained exterior finds balance in a more conventionally Eastern interior, lively with images and colours of nature.

So much of what we see in Massoudy’s art – the shapes and philosophies it returns to repeatedly – gain new resonance after a visit to the Sheikh Zayed Mosque – one of the largest mosques in the world and the ceremonial home of Islam in the UAE. In planning since the 1980s, the mosque was finally completed in 2007 – a delay more than accounted for by the sheer scope and detail of the building. Designed to reflect the international reach of Islam, the mosque housed under the billowing domes of white marble comprises raw building materials and craftsmen from some 20 different nations. A conversation between Mughal and Moorish architectures, the mosque’s restrained exterior finds balance in a more conventionally Eastern interior, lively with images and colours of nature.

The Qibla wall on which the 99 names of Allah are found is adorned with traditional Kufi calligraphy – the work of celebrated Emirati calligrapher Mohammed Mandi Al Tamimi – celebrating the national religion in a visual dialogue of faith and art. Outside, in the domed marble galleries, the white expanse is broken up with mosaics and vivid Iznik panels, their Turkish calligraphy catching the eye before releasing it upwards to the gilded tops of the four minarets that stand sentinel on each corner of the building.

The Qibla wall on which the 99 names of Allah are found is adorned with traditional Kufi calligraphy – the work of celebrated Emirati calligrapher Mohammed Mandi Al Tamimi – celebrating the national religion in a visual dialogue of faith and art. Outside, in the domed marble galleries, the white expanse is broken up with mosaics and vivid Iznik panels, their Turkish calligraphy catching the eye before releasing it upwards to the gilded tops of the four minarets that stand sentinel on each corner of the building.

The Abu Dhabi Festival may as yet be importing performing artists, consciously working to promote Emirati painters, musicians and dancers, but while the UAE may currently lack a national tradition of this kind, it is rich in the organic culture that forms such an essential part of Arabic and Islamic life. It is impossible (certainly to Western ears) to hear the guttural curlicues of the call to prayer, to walk through the meticulously designed spaces of any mosque or to see the lavish henna patterning on the arms of women, and doubt the creative urgency of the Emirati as a people.

Among the many quotations that animate Hassan Massoudy’s expressive, calligraphic paintings, one by Indian thinker Rabindranath Tagore speaks most directly: “The East and West are ever in search of each other, and must eventually meet.” This mutual reaching-out across cultures, this mutual search for common ground, is the spirit of the Abu Dhabi Festival and its dialogic fusion of styles and artists. As yet this dialogue is dominated – perhaps inevitably – by the West, with the best of international performance and art gathered into a city and a nation still under construction, still shaping its own creative identity. The festival’s coming of age will be the moment at which it and its Emirati artists take an equal role in the cultural conversation, sending their work out to us in the West with as much conviction and pride as they currently welcome ours.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

Goldscheider, Brother Tree Sound, Kings Place review - music of hope from a young composer

Unusual combination of horn, strings and electronics makes for some intriguing listening

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

theartsdesk Q&A: composer Donghoon Shin on his new concerto for pianist Seong-Jin Cho

Classical music makes its debut at London's K-Music Festival

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Helleur-Simcock, Hallé, Wong, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - moving lyricism in Elgar’s concerto

Season opener brings lyrical beauty, crisp confidence and a proper Romantic wallow

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Kohout, Spence, Braun, Manchester Camerata, Huth, RNCM, Manchester review - joy, insight, imagination and unanimity

Celebration of the past with stars of the future at the Royal Northern College

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jansen, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - profound and bracing emotional workouts

Great soloist, conductor and orchestra take Britten and Shostakovich to the edge

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Jakub Hrůša and Friends in Concert, Royal Opera review - fleshcreep in two uneven halves

Bartók kept short, and a sprawling Dvořák choral ballad done as well as it could be

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Hadelich, BBC Philharmonic, Storgårds, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - youth, fate and pain

Prokofiev in the hands of a fine violinist has surely never sounded better

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Monteverdi Choir, ORR, Heras-Casado, St Martin-in-the-Fields review - flames of joy and sorrow

First-rate soloists, choir and orchestra unite in a blazing Mozart Requiem

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Cho, LSO, Pappano, Barbican review - finely-focused stormy weather

Chameleonic Seong-Jin Cho is a match for the fine-tuning of the LSO’s Chief Conductor

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Classical CDs: Shrouds, silhouettes and superstition

Cello concertos, choral collections and a stunning tribute to a contemporary giant

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Appl, Levickis, Wigmore Hall review - fun to the fore in cabaret and show songs

A relaxed evening of light-hearted fare, with the accordion offering unusual colours

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Lammermuir Festival 2025, Part 2 review - from the soaringly sublime to the zoologically ridiculous

Bigger than ever, and the quality remains astonishingly high

Add comment