Jordi Savall, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse | reviews, news & interviews

Jordi Savall, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

Jordi Savall, Sam Wanamaker Playhouse

An early music pioneer goes solo by Shakespeare's Globe

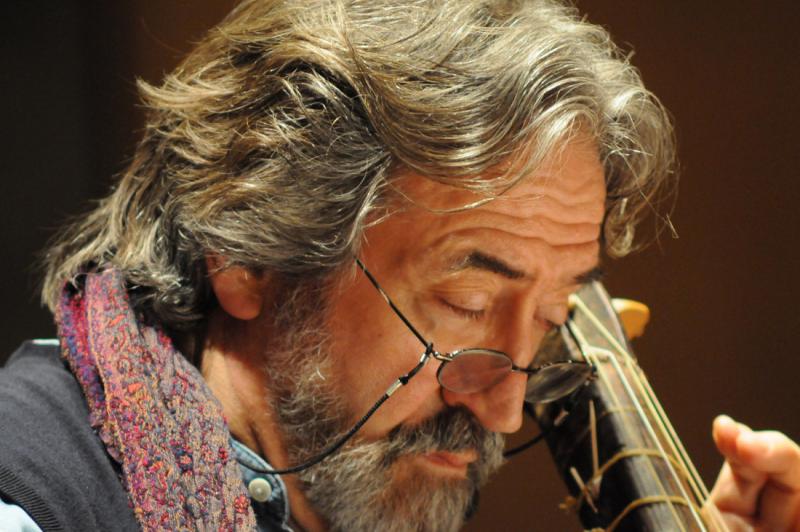

Jordi Savall has spent half a century combining instrumental performance on the viola da gamba with being the leader of ensembles of pioneering scholarship. Now in his early 70s, he has certainly had the recognition he deserves: a Grammy (he has made over a hundred albums), an honorary professorship (he has taught since 1974), and the Légion d'Honneur. These days he is also a prominent public figure supporting the “Catalunya should have the right to vote” campaign.

In Savall's programme note he remembers poring over the Tobias Hume Musicall Humours from 1605 in the Reading Room of the British Museum in 1964, getting microfiches of the collection developed, and then "trying to crack the code of those old notation systems and tablatures."

But the results are anything but dry. The recital showed above all that by digging deep into collections such as the Musicall Humours, or the Manchester Gamba Book (sic) of around 1660, Savall the performer can take the listener on a satisfying journey. We may have started in solitary contemplation with pavanes and laments, in which Savall showed mastery of both strict tempo and freer playing, but he led us right through - and without ever departing the works to be found in these collections - to strathspeys, hornpipes and jigs. He recorded the Musicall Humours in 1982 (a CD still available on Astrée) and his understanding has deepened further.

When he plays the quieter tunes pizzicato, Savall's shoulders turn in slightly, the instrument is cradled more delicatelyPatience is everything. Savall turns the tuning and the re-tuning of the instrument into an art-form in itself, always ending with a cadence and a flourish. And when he talked about his craft, he showed the respect with which he treats his instrument, a seven-string English bass viol from 1697: "When I talk, I give my instrument a chance to be stable."

It is indeed a close relationship between man and viol. When he plays the quieter tunes pizzicato (Tobias Hume's "Loves Farewell" for example, quite exquisite), Savall's shoulders turn in slightly, the instrument is cradled more delicately. As Savall also pointed out, the underhand bow grip for the viol puts the ring and fourth fingers in direct contact with the bow hair, and the performer can use this to affect bow tension, volume and articulation, a craft which was lost when technological advance introduced the metal screw to regulate the tension of the bow.

The candlelit Sam Wanamaker theatre was the right, intimate venue for this recital, but it was very hot, and the audience was packed very tightly. One audience member fainted and needed to be carried out - it was, ominously, not long after Savall had said that the piece listed in the programme as "Pavin - a Life" is in fact called Death - but he did recover.

Savall dealt with that incident serenely, completely aware of what was happening, but keeping concentration, and focus, and bringing us straight back to the music.This was a masterful recital by a unique figure in music.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Stile Antico, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious birthday celebration

Early music group passes a milestone still at the top of its game

Stile Antico, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious birthday celebration

Early music group passes a milestone still at the top of its game

Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - premiere of new Huw Watkins work

Craftsmanship and appeal in this 'Concerto for Orchestra' - and game-playing with genre

Hallé, Elder, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - premiere of new Huw Watkins work

Craftsmanship and appeal in this 'Concerto for Orchestra' - and game-playing with genre

First Person: young cellist Zlatomir Fung on operatic fantasies old and new

Fresh takes on Janáček's 'Jenůfa' and Bizet's 'Carmen' are on the menu

First Person: young cellist Zlatomir Fung on operatic fantasies old and new

Fresh takes on Janáček's 'Jenůfa' and Bizet's 'Carmen' are on the menu

Classical CDs: Chinese poetry, rollercoasters and old bookshops

Swiss contemporary music, plus two cello albums and a versatile clarinettist remembered

Classical CDs: Chinese poetry, rollercoasters and old bookshops

Swiss contemporary music, plus two cello albums and a versatile clarinettist remembered

La Serenissima, Wigmore Hall review - a convivial guide to 18th century Bologna

This showcase for baroque trumpets was riveting throughout

La Serenissima, Wigmore Hall review - a convivial guide to 18th century Bologna

This showcase for baroque trumpets was riveting throughout

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Isata Kanneh-Mason, Wigmore Hall review - family fun, fire and finesse

Intimacy and empathy in a varied mixture from the star siblings

Sheku Kanneh-Mason, Isata Kanneh-Mason, Wigmore Hall review - family fun, fire and finesse

Intimacy and empathy in a varied mixture from the star siblings

Mahler 8, LPO, Gardner, RFH review - lights on high

Perfect pacing allows climaxes to make their mark - and the visuals aren’t bad, either

Mahler 8, LPO, Gardner, RFH review - lights on high

Perfect pacing allows climaxes to make their mark - and the visuals aren’t bad, either

Philharmonia, Alsop, RFH / Levit, Abramović, QEH review - misalliance and magical marathon

Kentridge’s film for Shostakovich 10 goes its own way, but a master compels in his 13th hour of Satie

Philharmonia, Alsop, RFH / Levit, Abramović, QEH review - misalliance and magical marathon

Kentridge’s film for Shostakovich 10 goes its own way, but a master compels in his 13th hour of Satie

Bach St John Passion, Academy of Ancient Music, Cummings, Barbican review - conscience against conformism

In an age of hate-fuelled pile-ons, Bach's gospel tragedy strikes even deeper

Bach St John Passion, Academy of Ancient Music, Cummings, Barbican review - conscience against conformism

In an age of hate-fuelled pile-ons, Bach's gospel tragedy strikes even deeper

MacMillan St John Passion, Boylan, National Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, Hill, NCH Dublin review - flares around a fine Christ

Young Irish baritone pulls focus in blazing performance of a 21st century classic

MacMillan St John Passion, Boylan, National Symphony Orchestra & Chorus, Hill, NCH Dublin review - flares around a fine Christ

Young Irish baritone pulls focus in blazing performance of a 21st century classic

Classical CDs: Romance, reforestation and a Rolleiflex

New music for choir, orchestra and string quartet, plus a tribute to a rediscovered photographer

Classical CDs: Romance, reforestation and a Rolleiflex

New music for choir, orchestra and string quartet, plus a tribute to a rediscovered photographer

First Person: St John's College choral conductor Christopher Gray on recording 'Lament & Liberation'

A showcase for contemporary choral works appropriate to this time

First Person: St John's College choral conductor Christopher Gray on recording 'Lament & Liberation'

A showcase for contemporary choral works appropriate to this time

Add comment