"Late Style", the theme and title of pianist Jonathan Biss's three-concert miniseries, need not be synonymous with terminal thoughts of death. This recital ranged from introspection (Brahms), radiant simplicity (Schumann) and aphoristic minimalism (Kurtág) to robust self-assertion (the end of Chopin's Polonaise-Fantaisie, Brahms again), all of it guided by strength of intellect. Unfortunately the crespuscular, coffin-like interior of Milton Court's Concert Hall, even less attractive than the Queen Elizabeth Hall of memory and devoid of any floral touch, made any struggle for the light difficult, and its notorious acoustic played havoc with tonal clarity in the more tumultuous romanticism.

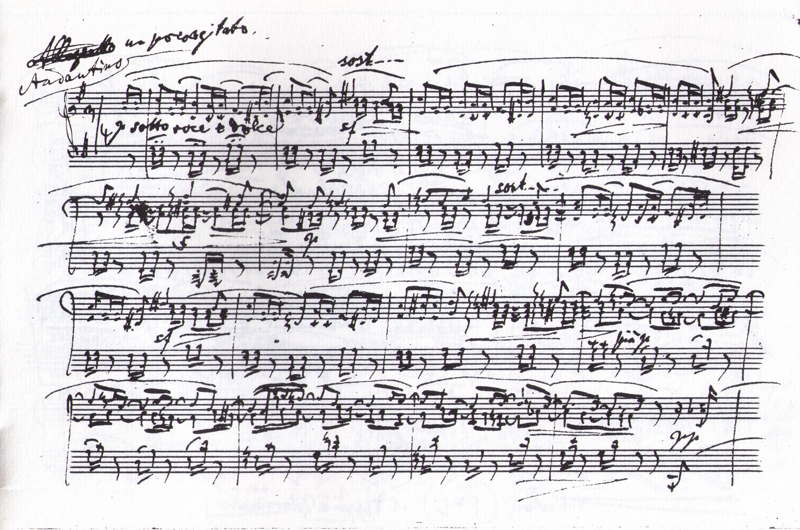

Not that Biss is a playful or fantastical pianist. On this evidence, at least, unsentimental firmness of purpose is his forte, and the second half of the programme, all Brahms, brought out the best in him (and the audience, perhaps, once it had adjusted to the plummy middle register which can surely, again, be blamed on the venue). Earlier, he'd spoken eloquently about why he wanted to preface the two last sets of piano pieces with the Andante espressivo of Brahms's Op. 5 Piano Sonata, its serene twilight chains of thirds contrasting with the more troubling ones of Op. 119's B minor Intermezzo. As a convenient diversion in between came the surprise last stage of the slow movement, a new and noble idea which Wagner surely adapted for the horn-throbbing coda of Hans Sachs's Act Two monologue in Die Meistersinger. By reversing the two sets - it's difficult to say when the actual pieces actually originated, but their order in each group should be unassailable - Biss left us not with the Pyrrhic victory of Op. 119's initially stout and steaky E flat Rhapsody but with the E flat minor blackness of Op. 118's obsessive finale. Along the way we heard all the necessary enigmatic beauty of the quieter numbers (pictured above: manuscript of the sotto voce Op. 119 No. 2), but with Brahms's meditation around the Dies Irae, that Latin chant for the dead which his natural successor Rachmaninov was to take up so relentlessly, the coffin lid slammed shut.

By reversing the two sets - it's difficult to say when the actual pieces actually originated, but their order in each group should be unassailable - Biss left us not with the Pyrrhic victory of Op. 119's initially stout and steaky E flat Rhapsody but with the E flat minor blackness of Op. 118's obsessive finale. Along the way we heard all the necessary enigmatic beauty of the quieter numbers (pictured above: manuscript of the sotto voce Op. 119 No. 2), but with Brahms's meditation around the Dies Irae, that Latin chant for the dead which his natural successor Rachmaninov was to take up so relentlessly, the coffin lid slammed shut.

Fortunately Biss opened it again by finding the end in the beginning, an encore reprise of the calm, chordal beauty in the first of Schumann's Gesänge der Frühe (Songs of Early Morning). Its opening context promised so well, but the Milton Court boominess soon set in with the second and third pieces, and conspired with Biss's fondness for the sustaining pedal in a conclusion to the Chopin which sounded not so much muddy as under water.

The echo-effect worked to Biss's advantage in the single lines of excerpts from György Kurtág's Játékok (Games), an ongoing series of "pedagogical studies", late but not last from the ever-fertile Hungarian. The selection eschewed humour, not a quality apparent anywhere in the concert, even in "Fugitive thoughts about the Alberti bass", but proved undeniably haunting. When the notes are stripped away, the venue can work to the soloist's advantage, but pianists beware: you'd be better off searching out the warmer if ruthlessly exposing acoustics of Kings Place's far lovelier concert hall.

Add comment