Benjamin Britten would have been 99 on the day of this concert. He died aged 62, nearly six months after the premiere of a masterpiece, the 15-minute "dramatic cantata" Phaedra, ruthlessly sifting key speeches from Robert Lowell’s translation of Racine. The compression of inspired, marble-hewn ideas, the like of which few contemporary composers come anywhere near in operas of two hours’ length or more, places Phaedra on a pedestal. Many of us would be happy to admire it in isolation, especially in the company of Alice Coote, a mezzo as equal to its stature as the original interpreter, Janet Baker. Here it crowned a bumper programme blending laments and arias with string music from the Britten Sinfonia which shook the foundations of the Wigmore Hall.

The light and the dark, which meet so pitilessly in Britten’s cantata, were kept apart in the first half. After the Rondeau from Purcell’s Abdelazar, purposefully stripped of the grandeur which Britten applied to introduce young persons to the orchestra, a trio of laments was not quite as expected. We heard Nico Muhly’s atmospheric presentation with its spooky halos around the entombed vocal line, rather than Britten’s "Purcell realisation", of Job's lament, "Let the night perish"; Coote fine tuned her spellbinding lowest range to the shifting string textures around her. We anticipated her remaining, poised as ever, centre-stage for Dido’s "When I am laid in earth", but got instead Leopold Stokowski’s uncharacteristically chaste, voiceless version.

In which company Tippett’s spirit of decorative delight shone in his own unmistakeable voice, fusing more sobriety from Dido and Aeneas with a dash of "Sellinger’s Round" projected by the Britten Sinfonia’s ardent violinist-director Jacqueline Shave. Coote returned to live and breathe the happy spirit of doughty Ruggiero in Handel’s Alcina, not a special Britten favourite, but a perfect leavening in this programme.

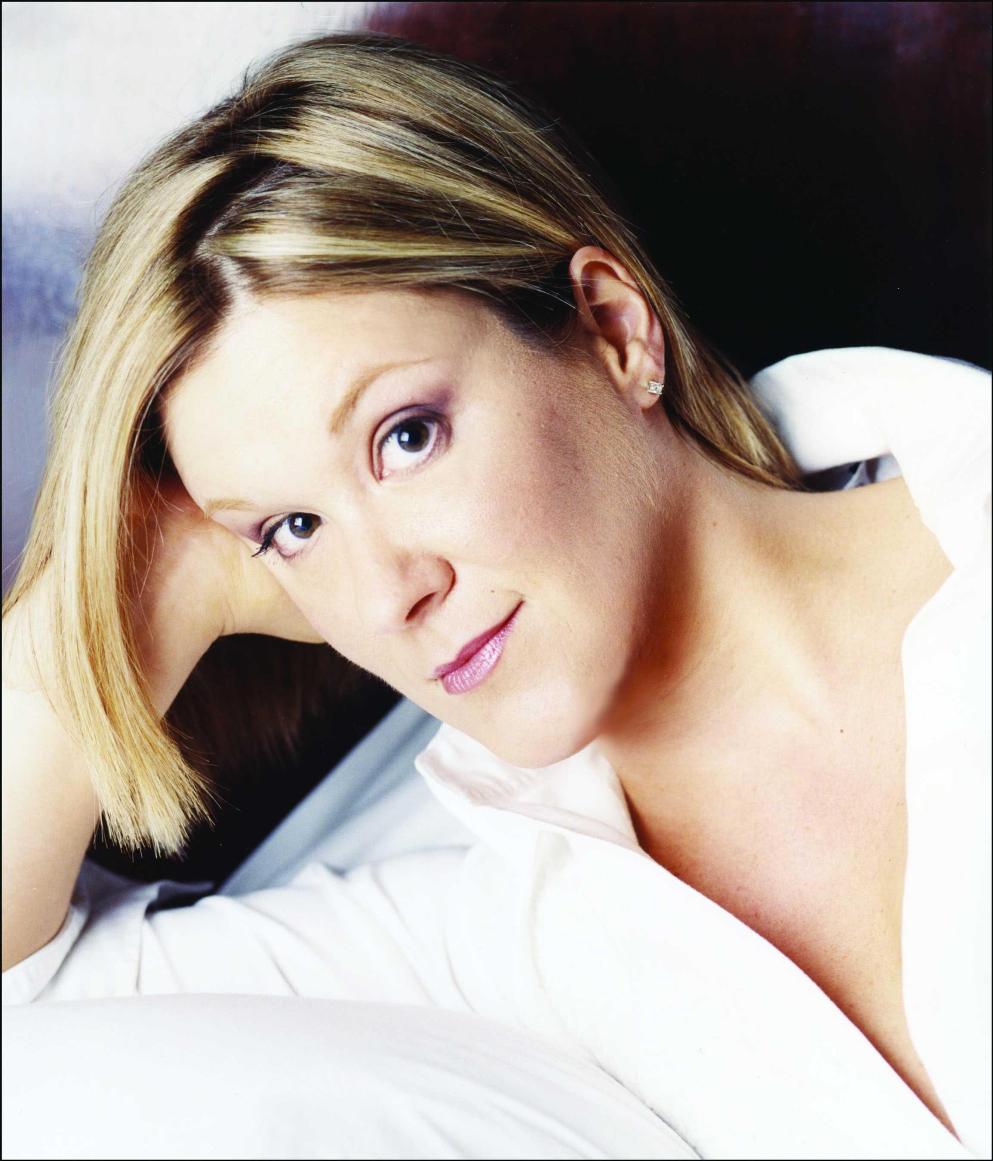

The da capos of Ruggiero's two gentle idylls favoured the inward tones which are among this great mezzo’s special conjuring tricks rather than any inappropriate ornamentation. Drama rather than fireworks kept the showy "Sta nell’Ircana" burning. Coote (pictured right) now presents a chest voice so electrifying that you fear it might detach from the warm middle range and a flawless top; but as yet there are no signs of a fatal break in this fabulous instrument. If the words occasionally disappeared, blame that on the acoustics of the crowded platform under the Wigmore dome.

The da capos of Ruggiero's two gentle idylls favoured the inward tones which are among this great mezzo’s special conjuring tricks rather than any inappropriate ornamentation. Drama rather than fireworks kept the showy "Sta nell’Ircana" burning. Coote (pictured right) now presents a chest voice so electrifying that you fear it might detach from the warm middle range and a flawless top; but as yet there are no signs of a fatal break in this fabulous instrument. If the words occasionally disappeared, blame that on the acoustics of the crowded platform under the Wigmore dome.

Britten and Tippett, one-time colleagues, shared a place in the sun with two utterly characteristic string pieces after the interval, neither of which I’d heard in concert before – and I wanted to hear them again, immediately. Shave's vivacious team was luminous in the assurance with which it etched the dashing centrepiece of Britten’s Prelude and Fugue and the long-limbed sense of grand play in Tippett’s far from Little Music for Strings.

Phaedra, with percussion and harpsichord joining the team to ratchet up the tension, needed a conductor, Richard Hetherington, to take fluent control from Shave. Even in a programme shot through with gravitas, there was one moment which went deeper than all the rest: the point at which Coote’s guilty heroine acknowledged the outcome of her adulterous passion by ascending the scale in Britten’s awe-inspiring setting of the line "Death to the unhappy’s no catastrophe".

Amplifying the sentiment in the ensuing Adagio, the strings turned the screw to set our heroine visibly on the rack, Coote’s features eventually subduing agonized spasms to form a tragic mask for the last rites. A pealing out of the most resplendent top A known to mezzos sealed her anguish at "Theseus, I stand before you" before the final miraculous control over the agony of death. The silence at the end signified that we’d all lived through an entire tragedy in a mere quarter of an hour. If there's a better realisation of Britten's distilled genius in centenary year, we will be lucky indeed.

Add comment