October, LSO, Strobel, Barbican review - Eisenstein with steel score | reviews, news & interviews

October, LSO, Strobel, Barbican review - Eisenstein with steel score

October, LSO, Strobel, Barbican review - Eisenstein with steel score

A head-spinning two hours with baroque imagery and heavy-metal music of 1927-8

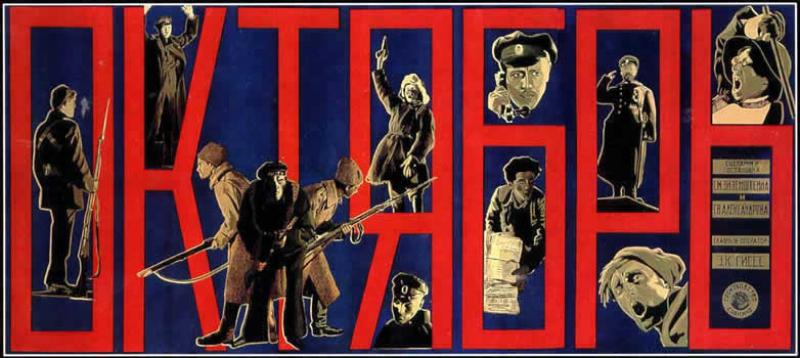

Forget the ersatz experience of Sergey Eisenstein's mighty silent films accompanied by slabs of Shostakovich symphonies composed years later. This collaboration between the London Symphony Orchestra and Kino Klassika is as close as we can ever come to hearing the massive score composed by Austrian-born Edmund Meisel for the greatest of the master's 1920s films.

Not that in one crucial respect any score can hope to reflect Eisenstein's most dazzling imaginative leaps. The "intellectual montage" yoking disparate images together and letting the viewer make the connections - most famously in his juxtaposition of religious objects from around the world found in the Hermitage Museum's ethnographic "cabinet of curiosities" to semi-satirise the old regime's banner of God and country - simply can't be reflected in music; any composer who attempted to do so would short-circuit the orchestra or the listener. In that respect, at least, Prokofiev had a more straightforward task in helping to create the "sound-cinema" Eisenstein was later to realise in Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible.

Instead Meisel, or rather Meiser/Thewes, attempts to capture the mechanical impetus of the Revolution in cyclopean blocks of sound, following the "style mécanique" launched by Honegger in Paris and taken up by the Russian composer Mosolov in the thrash of Zavod (The Iron Foundry). In this early heavy metal or proto-punk he succeeds brilliantly. Conductor Frank Strobel and a tireless London Symphony Orchestra not only manage feats of near-perfect synchronisation as they illustrate factory whistles with chord-cluster woodwind, marching troops with bow-slapping basses and the tearing-up of railway tracks with anvils; they also pull off the difficult job of keeping a steely clarity in the near-relentless thrashes which sometimes made you wish ear-plugs had been offered at the doors.

Instead Meisel, or rather Meiser/Thewes, attempts to capture the mechanical impetus of the Revolution in cyclopean blocks of sound, following the "style mécanique" launched by Honegger in Paris and taken up by the Russian composer Mosolov in the thrash of Zavod (The Iron Foundry). In this early heavy metal or proto-punk he succeeds brilliantly. Conductor Frank Strobel and a tireless London Symphony Orchestra not only manage feats of near-perfect synchronisation as they illustrate factory whistles with chord-cluster woodwind, marching troops with bow-slapping basses and the tearing-up of railway tracks with anvils; they also pull off the difficult job of keeping a steely clarity in the near-relentless thrashes which sometimes made you wish ear-plugs had been offered at the doors.

It's not all noisy - though when it is, which is most of the time, that's appropriate since Eisenstein keeps the ferment going from the toppling of Alexander III's statue by Kazan Cathedral, putatively in February 1917 - it actually happened in 1921, but as he wrote, "for the sake of truthfulness one can afford to defy the truth" - to the Bolshevik victory of October. When the tension needs more subtle strokes, as the director, having had free run of the Winter Palace, lingers on shaking chandeliers, or satirically depicts the Mensheviks' oratory as persuasive, woozy classical music, it gets them; the build-up before midnight on 25 October is appropriately tense. There's even a ballet divertissement earlier in the film as the Bolsheviks, having persuaded the Tatars in attendance on General Kornilov to respond to the appeals of "Bread! Peace! Land! Brotherhood!", join them in a dance competition. Parodies of the kind that the young Shostakovich would develop are mostly absent in Meisel's score, though the old bourgeoisie, meeting an inflexible young brute of a soldier on Petrograd's Gryphon Bridge, get a woozy brass treatment of the "Marseillaise" (Napoleon is invoked as provisional government leader Kerensky's idol, presumably to show where a first revolution - in this case the February Revolution - can lead). In propagandist terms, the ineffectual government and its pampered adherents get an unfair deal which includes harpy-ladies doing a young soldier to death with their parasols; Kerensky himself is the butt of comic relief (albeit not as pictured above). The Trotskyists, removed from the first cut by the Soviet censor, come off badly too. But Eisenstein is not unequivocal about the heroic people. Old peasant women loot a wine cellar on the night of the main uprising; true Bolsheviks show their contempt by smashing all the bottles and barrels; a hideous child rocks back and forth manically on the tsar's throne in one of the final images.

Parodies of the kind that the young Shostakovich would develop are mostly absent in Meisel's score, though the old bourgeoisie, meeting an inflexible young brute of a soldier on Petrograd's Gryphon Bridge, get a woozy brass treatment of the "Marseillaise" (Napoleon is invoked as provisional government leader Kerensky's idol, presumably to show where a first revolution - in this case the February Revolution - can lead). In propagandist terms, the ineffectual government and its pampered adherents get an unfair deal which includes harpy-ladies doing a young soldier to death with their parasols; Kerensky himself is the butt of comic relief (albeit not as pictured above). The Trotskyists, removed from the first cut by the Soviet censor, come off badly too. But Eisenstein is not unequivocal about the heroic people. Old peasant women loot a wine cellar on the night of the main uprising; true Bolsheviks show their contempt by smashing all the bottles and barrels; a hideous child rocks back and forth manically on the tsar's throne in one of the final images.

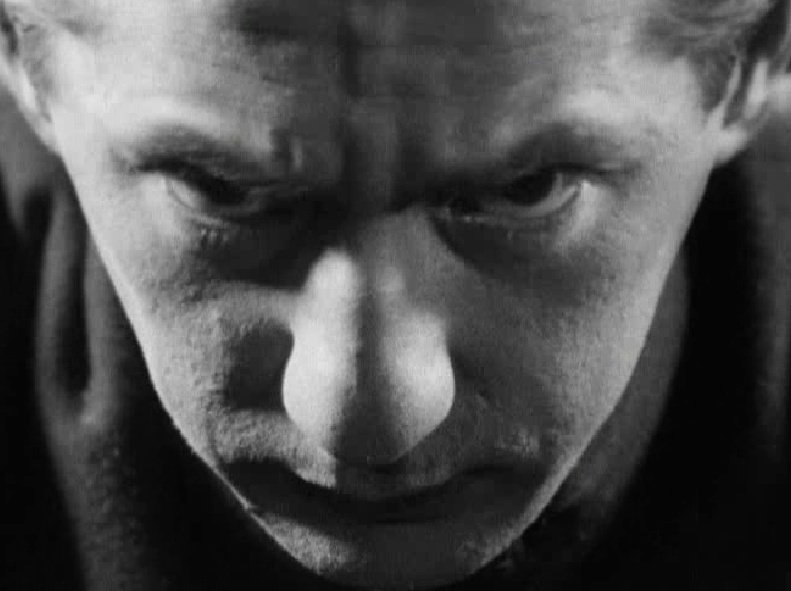

It's astonishing how Eisenstein's inventiveness refuses to rest. He keeps fine detail in the picture, even between scenes of ant-like mass activity; given the run of Leningrad, he raises bridges, showing the long hair of a dead young woman revolutionary slowly falling into the gap and - most famously - the corpse of a horse hanging from the heights. Here Meisel's score (the composer pictured right) does one of its justifiable tricks of modulating ever upwards, semitone by semitone; when the bridges are lowered later, he goes back down (in the brilliant and outrageous sequence where the smashed statue of Alexander III pieces itself together again, I didn't notice the technique Eisenstein claims Meisel used of writing out the original musical depiction backwards, Berg-style).

It's astonishing how Eisenstein's inventiveness refuses to rest. He keeps fine detail in the picture, even between scenes of ant-like mass activity; given the run of Leningrad, he raises bridges, showing the long hair of a dead young woman revolutionary slowly falling into the gap and - most famously - the corpse of a horse hanging from the heights. Here Meisel's score (the composer pictured right) does one of its justifiable tricks of modulating ever upwards, semitone by semitone; when the bridges are lowered later, he goes back down (in the brilliant and outrageous sequence where the smashed statue of Alexander III pieces itself together again, I didn't notice the technique Eisenstein claims Meisel used of writing out the original musical depiction backwards, Berg-style).

Above all the director makes himself curator of the Hermitage, filming hundreds of serried plates, boxes of medals - "did we fight for this?," asks a soldier - and the Tsarina's bedroom with its excess of icons and Fabergé eggs. There's a brilliant article on this by Oksana Bulgakowa in the programme. Into this labyrinth, the works of art lovingly filmed but parodically juxtaposed with harsh reality, Meisel's score cannot hope to accompany Eisenstein. But it does keep the fever-pitch, hallucinatory quality going with its endless marches and ostinati. One question remains: if the Russian Orthodox Church, brutally mocked here (in the image pictured above, among others, seen in the Barbican rehearsal), is currently campaigning in its sanctification of Nicholas II against the screening of a bodice-ripper featuring the Tsar's ballerina mistress Matilda Kschesinskaya, will its complicity with murderous power outlaw Eiseinstein's masterpiece yet again in an imperialist Russia? In the meantime, widespread DVD release of the full film with the full score on DVD - a CD of the music would be excessive - is an absolute priority*.

One question remains: if the Russian Orthodox Church, brutally mocked here (in the image pictured above, among others, seen in the Barbican rehearsal), is currently campaigning in its sanctification of Nicholas II against the screening of a bodice-ripper featuring the Tsar's ballerina mistress Matilda Kschesinskaya, will its complicity with murderous power outlaw Eiseinstein's masterpiece yet again in an imperialist Russia? In the meantime, widespread DVD release of the full film with the full score on DVD - a CD of the music would be excessive - is an absolute priority*.

*My thanks to a reader for pointing me in the direction of an Eisenstein/Meisel Battleship Potemkin and October double-bill DVD available through the German Edition Filmmuseum.

- 7 November is Revolution Day on BBC Radio 3. David Nice's selection, translation and presentation of excerpts from Prokofiev's 1917 diary, with readings by Samuel West, will be broadcast throughout the day

- Read more classical music reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

David - you're right: an

That's not the only thing

That's not the only thing wrong in the autobiography, Immortal Memories - he attributes the sequence to Battleship Potemkin. Very few references to Meisel anywhere else in his writings - maybe you know more than I do. Have to get the German edition - presumably you have it.

The autobiography isn't a