"From today, painting is dead" was the forlorn conclusion of French painter Paul Delaroche on seeing a photograph for the first time in 1839. His gloomy prediction was premature, of course; more than 170 years on, the battle for supremacy is still raging.

Divided into genres such as Portraiture, The Figure and Still Life, the National Gallery’s first exhibition of photography follows the twists and turns of this ongoing war. The main casualty of the clash turns out not to be painting but engraving, the medium most often used to disseminate images prior to the invention of the camera. One of the snippets of information brought to light by this fascinating exhibition is that Roger Fenton, famed for his photographs of the Crimean War, augmented his income by photographing old master paintings or, better still, engravings because the black and white copies were more readily available and easier to reproduce than the originals.

Henry Fox Talbot, another pioneer, called the new medium "the pencil of nature", implying that because the images were made directly by light, they were more truthful than drawings or paintings. At the foot of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, 1514, two plump cherubs lean on a ledge. The two children in O.G. Rejlander’s 1857 homage maintain similar poses by resting their arms on a box; according to a contemporary reviewer, this cute copy "tests Raphael by nature and beats him hollow".

Henry Fox Talbot, another pioneer, called the new medium "the pencil of nature", implying that because the images were made directly by light, they were more truthful than drawings or paintings. At the foot of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna, 1514, two plump cherubs lean on a ledge. The two children in O.G. Rejlander’s 1857 homage maintain similar poses by resting their arms on a box; according to a contemporary reviewer, this cute copy "tests Raphael by nature and beats him hollow".

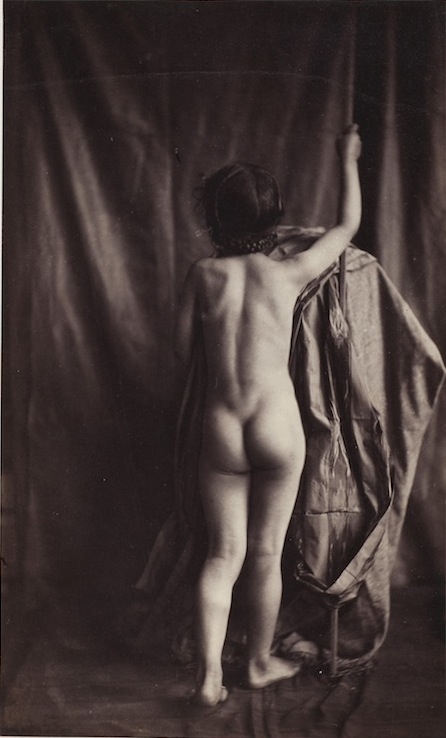

Models were expensive to hire, so painters often relied for source material on anatomical engravings. These aroused in Delacroix "a feeling of revulsion, almost disgust for their incorrectness, mannerisms, and their lack of naturalness". Spotting an opportunity, photographers soon began supplying artists with male and female nudes in suitable poses. These "poorly built, oddly shaped... and not very attractive" specimens didn’t live up to the ideal of the academic nude, yet Delacroix claimed to learn "far more by looking (at them) than the inventions of any scribbler" and in 1853 he commissioned Eugène Durieu to photograph a series of nudes (pictured above right, © Gregg Wilson), which he helped to pose and light.

For many, though, veracity was not the issue. Photographers like Julia Margaret Cameron were keen to be accepted as artists, rather than just recorders of reality. Her version of a cupid is a child with wings, which attempts to outdo Raphael by evoking the inner world of the sulky model. With its richly dark sepia tones, her "Iago" is clearly inspired by Rembrandt’s portraits; the model’s introspective gaze and chiselled solemnity are intended to convey his inner being as convincingly as any Rembrandt. “My whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty,” she said, “in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man."

The struggle for acceptance as an art form would not fully be won for another hundred years. Nowadays, though, photographs are exhibited and sold alongside paintings, drawings and sculptures and have been joined by other "new" media such as film and video; while early photographs by pioneers such as Fenton and Cameron are an established part of the artistic canon. Seduced by Art therefore weaves a complex picture in which citations may be multi-layered – paying homage as much to photographs as Old Master paintings.

The struggle for acceptance as an art form would not fully be won for another hundred years. Nowadays, though, photographs are exhibited and sold alongside paintings, drawings and sculptures and have been joined by other "new" media such as film and video; while early photographs by pioneers such as Fenton and Cameron are an established part of the artistic canon. Seduced by Art therefore weaves a complex picture in which citations may be multi-layered – paying homage as much to photographs as Old Master paintings.

Nicky Bird recently spent time tracing the descendants of Cameron’s sitters on the Isle of White and, although not related to her, Bird’s niece Jasmin could easily be the sister of Kate Keown (pictured left above, © Gregg Wilson), who posed for Cameron 135 years earlier. The juxtaposition of photographs with probable sources of inspiration is not always as convincing as this pairing, though. Last year Richard Learoyd photographed a man naked save for a necklace and giant octopus tattooed across his left side. This arresting image (pictured overleaf: Man with Octopus Tattoo II) is hung beside a photograph of the Laocoön, a sculpture from 25 BC of a Trojan priest and his two sons hopelessly entwined in the suffocating coils of a sea serpent.

Resemblances between the octopus and sea serpent are superficial, though; more importantly, the pose of the tattooed man is based on The Small Bather, Interior of a Harem (1828) by Ingres, which focuses on the sinuously curved back of a naked woman seated beside a pool. By inviting comparison between a male and female nude, Learoyd encourages us to see his model as an erotic object – or sex slave, an idea that is still quite shocking.

Resemblances between the octopus and sea serpent are superficial, though; more importantly, the pose of the tattooed man is based on The Small Bather, Interior of a Harem (1828) by Ingres, which focuses on the sinuously curved back of a naked woman seated beside a pool. By inviting comparison between a male and female nude, Learoyd encourages us to see his model as an erotic object – or sex slave, an idea that is still quite shocking.

Since the smooth surface of a photograph is as unlike the texture of paint on canvas as chalk from cheese, hanging a photograph next to a painting can seem horribly discordant. A case in point is Jeff Wall’s The Destroyed Room (1978) (main picture), which is hung near an oil sketch of Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus (1827). The oil copy is faithful to the original, which shows the defeated King of Assyria reclining on a divan watching his harem slaves being murdered around him. Wall has chosen a moment of stillness after the marauders have gone, leaving behind a scene of devastation. Intended to be as eye-catching and immediate as an advert, the large, back-lit transparency totally eclipses the subtler voice of the oil study.

Some photographs have migrated to other galleries to hang beside the pictures that inspired them. It's an interesting idea but produces jarring results, since the language of photography is so different from that of drawing or painting. Printed on textured paper that produces a stippling effect reminiscent of pastel, Craigie Horsfield’s monochrome nude hangs beside a Degas pastel; yet despite Horsfield’s attempts to enliven its surface, the print seems ludicrously out of place.

Some photographs have migrated to other galleries to hang beside the pictures that inspired them. It's an interesting idea but produces jarring results, since the language of photography is so different from that of drawing or painting. Printed on textured paper that produces a stippling effect reminiscent of pastel, Craigie Horsfield’s monochrome nude hangs beside a Degas pastel; yet despite Horsfield’s attempts to enliven its surface, the print seems ludicrously out of place.

The most satisfying juxtaposition is Nadar’s 1864 portrait of actress Sarah Bernhardt with a self-portrait by the Scottish poet and photographer Maud Sulter (pictured above left as Calliope from the Zabat series, 1989 © the estate of Maud Sulter). To celebrate the publication of Zabat, her book of poetry, she poses as Calliope, the muse of epic poetry. Like Bernhardt, she sits wrapped in a velvet drape; the luscious tonality of Nadar’s silver bromide print is translated into dark greens, browns and blacks. This sumptuous image is a fitting tribute to her own and other women’s achievements.

Watch Maisie Broadhead and Jack Cole’s video Ode to Hill and Adamson commissioned by the National Gallery, which recreates an 1844 portrait of Elizabeth Rigby

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment