Captured in monochromes ranging from the most delicate honeyed golds to robust gradations of aubergine and deep brown, the earliest photographs still provoke a shiver of surprise and excitement. Even now, their very existence seems miraculous, and the blur of a face, or the lost swish of a horse’s tail signifies the photographer’s pitched battle with time, never quite managing to make it stop altogether. And with their chemical concoctions, their images emerging gradually, apparently from within the paper itself, it is no wonder that from the outset the photographer’s art was cloaked in the mystique of alchemy and magic.

By 1839, William Henry Fox Talbot in England and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in France had each found quite different means by which to “fix a shadow”, the evocative terms through which Talbot himself described his invention. Talbot’s method, using light-sensitive paper to produce a negative which could then be printed as a positive, produced an image considerably less refined than Daguerre’s unique positive image, but its reproducibility would become one of photography’s defining characteristics. Lacking the near-perfect resolution of the daguerrotype, Talbot’s salted paper prints had an aesthetic appeal of their own, a softness and a velvety depth that speaks to the sensibilities of painting and drawing. Developed by Talbot as a means of overcoming his own lack of drawing ability, the salt print quickly gained currency as an expressive medium.

Talbot’s early photographs are brimming with the spirit of experimentation, and in his choice of subjects – friends and family, street scenes and natural objects – he busily explores photography’s potential, testing its limitations and acquiring a new-found wonder at the world as it could be represented in the new medium.

Talbot’s early photographs are brimming with the spirit of experimentation, and in his choice of subjects – friends and family, street scenes and natural objects – he busily explores photography’s potential, testing its limitations and acquiring a new-found wonder at the world as it could be represented in the new medium.

His careful arrangements of china and glass serve both as a scientific experiment and a promotional tool. They allowed him to note the differing exposure times required by china and glass and the light-reflecting properties of different colours, observations that would become significant when trying to judge exposure times out in the field. But perhaps more surprisingly to our modern eyes, the pictures show that a transparent object could indeed be successfully photographed and that unlike drawing, multiple objects could be recorded in the time that it would take to photograph just one. The comparison with painting and drawing is there again in Talbot’s beautiful image of a tree in the dead of winter, each branch and hair-like twig picked out as if to say, “now imagine how long it would take to draw that".

By 1841, Talbot had dramatically reduced, from many minutes to just seconds, the exposure time needed to produce a negative, and on a trip to Paris to publicise his new calotype process he took a picture from his hotel room window, an instinctive piece of photojournalism (main picture). The buildings opposite are rendered in precise and exquisite detail, the black and white stripes of the shutters neat alternations of light and shade. In contrast to the solidity of the buildings are the carriages waiting on the street below; the wheels, immobile, are seen in perfect clarity, while the skittish horses are no more than ghostly blurs.

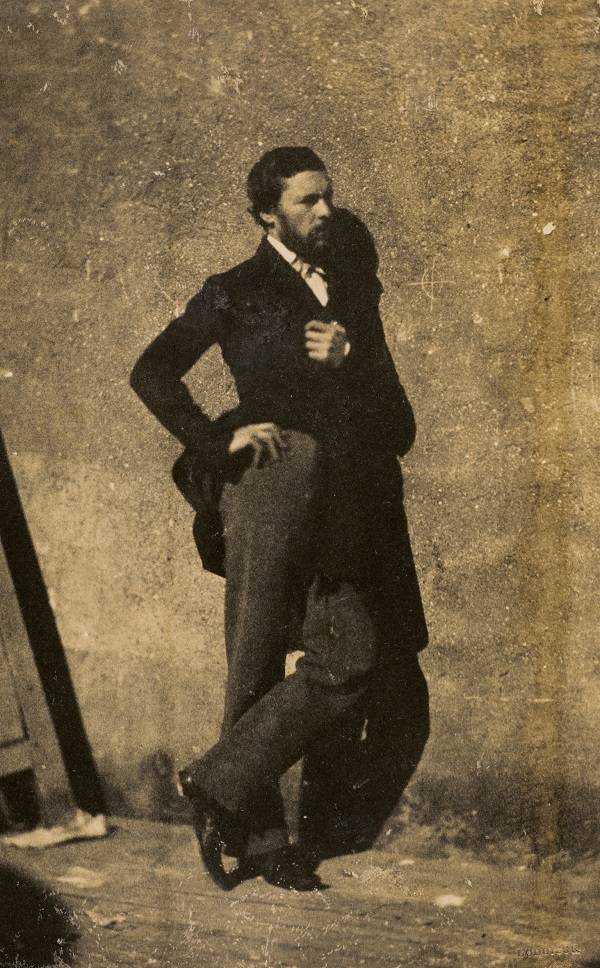

As growing numbers of pioneers adopted Talbot’s invention and began photographing the world around them, portraiture emerged early on as a genre, and in a variety of forms. We see the beginnings of the stiff Victorian portrait but more surprising are the very many experimental and informal images that were produced. A group of fishermen, their faces, modelled in blocks of light and shade, seem to have been caught candidly, and yet they must have been standing still for some time. And in his portrait of a man lent against a wall, Louis Crette allows his subject’s shadow as much substance as his clothing, the deep velvety black contrasting with the rough texture of the wall (Pictured above right: A Lesson of Gustave Le Gray in his Studio, 1854).

Just as portraiture showed little regard for social class or traditional ideas of beauty, so the camera treated all aspects of modern life with an even hand. In the decades before Impressionism, photographers marvelled at the world around them in all its manifestations, photographing the new industrial architecture, and devastated, flood-damaged buildings with the same care as they took over images of revered ancient buildings.

Even in these early years, one of photography’s enduring problems became evident, however. One of the most beautiful photographs in this exhibition is Paul Marès Ox Cart, Brittany, c.1857 (pictured left). At first it seems a picturesque scene of bucolic tranquillity, the abandoned cart an exquisite study in light and tone. But on the cottage wall are painted two white crosses, a warning – apparently even as recently as the 19th century – to passers-by that the household was afflicted by some deadly disease. Photography’s ability to indiscriminately aestheticise is a dilemma that has continued to present itself ever since, especially in the fields of reportage and war photography.

Even in these early years, one of photography’s enduring problems became evident, however. One of the most beautiful photographs in this exhibition is Paul Marès Ox Cart, Brittany, c.1857 (pictured left). At first it seems a picturesque scene of bucolic tranquillity, the abandoned cart an exquisite study in light and tone. But on the cottage wall are painted two white crosses, a warning – apparently even as recently as the 19th century – to passers-by that the household was afflicted by some deadly disease. Photography’s ability to indiscriminately aestheticise is a dilemma that has continued to present itself ever since, especially in the fields of reportage and war photography.

In fact, this relatively small group of pictures could almost serve as a manifesto proclaiming the concerns that would dominate photography in the 20th century, and in defining the new medium barely a stone was left unturned in these first 20 years. Beautifully hung, and with minimal distractions from accompanying texts, the curators have boldly and quite rightly decided that the technical details can be dispensed with, widely available as they are on the internet and in books.The only thing to do here is look.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment