It could be an aircraft, hastily covered with some very inadequate wrappings and squeezed into the great hangar of the Turbine Hall. Or perhaps an eccentric sort of bird, its bedraggled wings missing chunks of orange plumage, in contrast to its plush, red body. Or perhaps it is part of a stage set with extravagant swags of red fabric carefully arranged to look, fleetingly, like theatre curtains, or pieces of scenery either under construction or partially wrapped, ready to be put away.

Pulled and gathered at points, the towering red central section of this vast new sculpture sometimes resembles a button-back chair, the fabric pinned to suggest the yielding bulk of upholstery, until occasional gaps reveal dark voids, hinting at something rather more mysterious beneath, or alternatively, nothing at all. Perhaps the thing, whatever it is, is yet to be revealed, and we are looking at mere wrappings. Certainly, the use of fabric, so often a material for covering and concealing, is highly suggestive, and a great mound of red fabric collected into busy peaks and folds as if squirted from a can implies a process of concealment interrupted, the tiny diamond shapes cut into the cloth inviting us to hunt for something beneath the surface (detail pictured below).

Even when the guts of the sculpture, or perhaps more fittingly its bones, are revealed in the great wing-like structures either side, we cannot be entirely sure of what it is we are looking at. Sparsely covered in a rich, orange fabric, the great wood and metal frame seems to be woven in with it; sometimes, the fabric appears to be sucked into some dark crevice of the frame, or even disgorged from it, confusing our sense of what is surface and what belongs underneath.

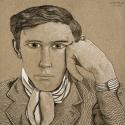

The great pleasure, and it is pure, simple pleasure, of this new commission from Richard Tuttle, veteran of the 1960s New York art scene, is that it is a puzzle with infinite or no solutions. Anticipating our need to give the sculpture an identity, the title responds with a good-humoured but resolute shrug of the shoulders. To our, "What is it?" Tuttle offers a straightforward I Don’t Know, and so begins what is, throughout, a hugely enjoyable dialogue.

The great pleasure, and it is pure, simple pleasure, of this new commission from Richard Tuttle, veteran of the 1960s New York art scene, is that it is a puzzle with infinite or no solutions. Anticipating our need to give the sculpture an identity, the title responds with a good-humoured but resolute shrug of the shoulders. To our, "What is it?" Tuttle offers a straightforward I Don’t Know, and so begins what is, throughout, a hugely enjoyable dialogue.

Non-committal it might be, but the second half of the title, The Weave of Textile Language, does offer us some clue as to the concerns of I Don’t Know . If nothing else, the sculpture is an exploration of the material qualities of fabric, and speaks of the artist’s long-held fascination with fabric as both material and metaphor. In its exploration of texture, colour, reality and illusion and the evocation of volume and mass, the sculpture revisits themes that have recurred throughout Tuttle’s career, and that are explored in some detail in a retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery, which focuses on Tuttle’s interest in textiles.

Interestingly, it is in early work from the 1960s and '70s that the most telling connections are made. A world away from the prescriptive tendencies that characterised much art of the 1960s, Tuttle’s Cloth Pieces of 1967 give no indication of which way up they should be hung, or even of front and back. As a piece of unstretched canvas, a work like Purple Octagonal, 1967, looks different each time it is displayed, and the interchangeability of front and back, top and bottom echo the loosely defined surfaces of the Tate sculpture.

Wire Pieces, 1971-2, further highlights the illusory nature of Tuttle’s work. Barely visible against a white wall, a pencil line marks where a piece of wire once was. Released from the wall, the wire has sprung back into a form of its own, casting a shadow, or set of shadows as it does so. Which line is more "real", the pencil line that is a ghost of what once was there, or the impermanent shadow, an echo of something that exists still, is a puzzle all of its own.

- Richard Tuttle at Turbine Hall, Tate Modern until 6 April, 2015 and Whitechapel Gallery until 14 December

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment