In a tavern somewhere in Tokyo, two Japanese macaque monkeys work a daily, two-hour shift (under Japanese law, these hours are regulated). Dressed in miniature uniforms, the monkeys’ main task is to deliver hot towels to amused customers before drinks orders are taken by a human. The customers tip the monkeys in boiled soy beans.

A search on YouTube throws up quite a few of these monkey-waiter skits. Who knew? Perhaps all the footage comes from the same restaurant, since it seems unusual enough to have warranted a jolly “strange but true” item on Japanese news. One segment of this news footage shows one of the monkeys wearing a human mask – a rather grotesque, plump-lipped, little-girl mask, with long, dark hair attached to it, which sways gaily as the monkey moves with its swift, lolloping gait.

This disconcerting monkey-waiter business seems to have been the inspiration for Pierre Huyghe’s film Human Mask (main picture), but here a mood that’s eerily apocalyptic prevails. A street lined with abandoned buildings and speaking of the aftermath of some disaster features in the opening scene. The camera then enters a dim, deserted interior. It’s the long, dark hair we see first; then, as the creature turns, we see what is a mask – a mask as white and smooth as porcelain, with serene, blankly beautiful features. The real-life monkey wears a blue, buttoned dress with a trim, white collar. We follow this anthropomorphised creature as it moves through the rooms of the restaurant, or simply sits, one leg tapping or swinging, on a chair, to which it seems appropriate to give alternate readings of ennui, agitation and restiveness. Occasionally we see a watchful cat, but no other living presence.

Alone, the monkey follows its, perhaps not wholly natural, instincts: alert to sounds, opening doors, picking at its front claw – perhaps something is lodged under a nail – and seeming simply to wait. Imprisoned behind its human mask, the camera goes for a close-up of the eyes in the final shot. The eyes dart hither and thither. What sense does it make of the world behind that mask? Those eyes seem both innocent and accusing. End.

The film appears to offer a mute commentary on a future environmental dystopia, even hinting, at its edges, the possibility of hybrid animal-human mutations between close primates – them and us. Naturally, we are forced to note how like us this creature appears, although we and Huyghe are surely as knowingly complicit in our anthropomorphism as anyone who outrightly exploits a human likeness, which is of course why we find the film, which is beautifully shot, both fascinating and unsettling. Huyghe bleeds all the cuteness out of the monkey-waiter skit, and confronts us instead with our own too-human follies. With its air of strangeness and pathos, the film’s moral purpose seems clear.

A second film in the exhibition is shot with a microscopic camera. Here we glimpse the body parts of apparently huge insects – a massive compound eye, whose surface seems to shift as the shot dissolves, a fat, furry leg jutting out at a threatening angle, a prickly exoskeletal body. The creatures appear submerged in bubbling, murky water, though they are in fact encased in amber and are several million years older than human life on earth The film is accompanied by a cranked-up soundtrack of the sharp click and whir of the camera, forensically foraging for this prehistoric life beneath the preserving layers of sediment.

With his decapitated, moss-covered sculpture of a reclining, antique-looking figure – actually a piece cast in concrete and with its original dating only to 1931 – and three murky aquariums which periodically light-up to reveal some fish, Huyghe has also created a mise-en-scène that speaks of civilisation’s end. But additional information about the “biotopes” being from Monet’s ponds in Giverny, while the lighting sequence is “programmed according to a fast-paced rendering of the variations in weather conditions as recorded at Giverny between 1914 and 1918, when Monet painted the ‘Nymphéas”, seems a tad over-conceptualised. These theatrical set pieces add little, or possibly too much. (Pictured above right: Nymphéas Transplate, foreground, and La Déraison, 2014)

With his decapitated, moss-covered sculpture of a reclining, antique-looking figure – actually a piece cast in concrete and with its original dating only to 1931 – and three murky aquariums which periodically light-up to reveal some fish, Huyghe has also created a mise-en-scène that speaks of civilisation’s end. But additional information about the “biotopes” being from Monet’s ponds in Giverny, while the lighting sequence is “programmed according to a fast-paced rendering of the variations in weather conditions as recorded at Giverny between 1914 and 1918, when Monet painted the ‘Nymphéas”, seems a tad over-conceptualised. These theatrical set pieces add little, or possibly too much. (Pictured above right: Nymphéas Transplate, foreground, and La Déraison, 2014)

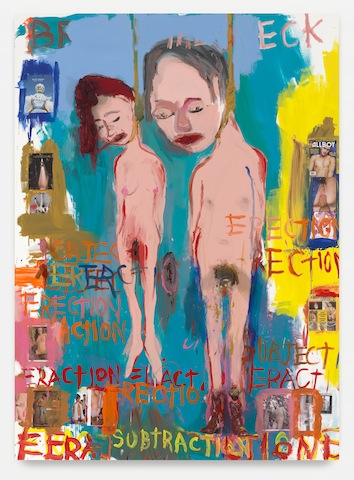

At Hauser & Wirth’s gallery next door, there’s an unrelated exhibition of Paul McCarthy’s new paintings. Painting is not a medium readily associated with this LA artist, who is better known for "gross-out" video performances featuring characters from children’s fiction, and phallic Disney inflatables, and latterly that huge butt-plug Christmas tree in Paris. Some of the paintings are apparently riffing on Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe and Olympia, while others on cowboy film Stagecoach (references, too, to Snow White and Walt Disney, both McCarthy mainstays). But that’s hardly the most obvious or noteworthy detail about them. The 14 big paintings, all painted this year, plus a series of drawings, show crudely painted figures involved in fetishised sexual acts: autoerotic asphyxiation, coprophilia, emetophilia, various sadomasochistic acts of sexual humiliation and cruelty, including, lo, decapitation.

Accompanying the painted imagery are scrawled words – “cut off penis”; cut off head” (much of the sexual violence is perpetrated by the women and directed at the men, which is interesting) – and collaged pages from glossy magazines (ads for expensive perfumes, etc), the covers of art journals and pages from specialised porn mags (hey, they’re all part of the same hyper-consumerist shit, man). Mouths smeared or crammed with shit and anal shots – eww, haemorrhoid-butts, yes, even those – feature heavily. James Franco pops up in one painting, an actor-celebrity-artist who might be full of shit but is here only smeared with a light splattering of paint. (Pictured left: SC, ECK, 2014)

Accompanying the painted imagery are scrawled words – “cut off penis”; cut off head” (much of the sexual violence is perpetrated by the women and directed at the men, which is interesting) – and collaged pages from glossy magazines (ads for expensive perfumes, etc), the covers of art journals and pages from specialised porn mags (hey, they’re all part of the same hyper-consumerist shit, man). Mouths smeared or crammed with shit and anal shots – eww, haemorrhoid-butts, yes, even those – feature heavily. James Franco pops up in one painting, an actor-celebrity-artist who might be full of shit but is here only smeared with a light splattering of paint. (Pictured left: SC, ECK, 2014)

I’ve never been entirely sure about McCarthy. To say his work packs a visceral punch is to avoid admitting how much of his early work – those videos – is actually almost too unbearable to watch, as it relentlessly, and at considerable length which surely tests endurance, pounds away at some sexual taboo or injury in a way that appears so raw, so existentially anguished, that it feels like you’re witnessing a person in extremis both acting out and disintegrating. One woman overheard in this present exhibition said she thought these paintings funny, which struck me as a dishonest response. Unable or unwilling to identify the nature of a psychic disturbance, a common response is to claim be amused. OK, a common response is also to actually laugh – but saying you find something “funny” and then not laughing seems to be doubly dishonest. Amusement is the go-to defence against all sorts of complex feelings, including bafflement, but does McCarthy’s paintings demand detached, sophisticated, artworld amusement? To whom would that pay a compliment? Him or us? That’s not to say he never uses humour – he certainly uses humour as part of his armoury – but it's not acerbic comedy humour, and its relationship to making us laugh is a doubtful one. He uses cuddly toys but it’s not to make us feel warm and reassured.

I’ve never been entirely convinced about McCarthy because so much of his language seems incredibly hackneyed. Pouring oil on the gallery floor to say something about the Gulf War, or the war in Iraq, or practically any war, and making huge comic effigies of Bush being mechanically rogered by pigs – it might amuse him to know that his work will be sold to those despised cigar-chewing collectors who would all probably prefer a Bush to an Obama, but that doesn’t raise the stakes of the work in any seriously interesting way.

But here, the sheer epic scale of his misanthropy – undeniable in its Swiftian reach – shows itself to be so deep, so raw, so genuine, that, despite the clapped-out, almost lazily cynical triteness of recent pieces (bar the brilliant wit of that butt-plug Christmas tree), it demands a different response. How can one not be impressed by a body of work that comes at you in such an oxygen-consuming fireball of rage?

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment