Artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah’s multi-screen film installation Vertigo Sea is an epic meditation on mankind’s relationship with the watery world. Exploring themes of migration, environmental destruction and slavery, it was one of the most talked about works at last year’s Venice Biennale. Now at Bristol’s Arnolfini, the location couldn’t be more fitting. Housed in an old warehouse, the gallery is just a stone’s throw from the city’s floating harbour, near where, three centuries ago, ships arrived laden with human cargo.

Akomfrah took his cue from a radio interview with young Nigerian migrants who survived an illegal crossing of the Mediterranean by clinging onto nets on the side of a fishing ship. They recalled that the ocean was greater and more awesome than they could ever have possibly imagined.

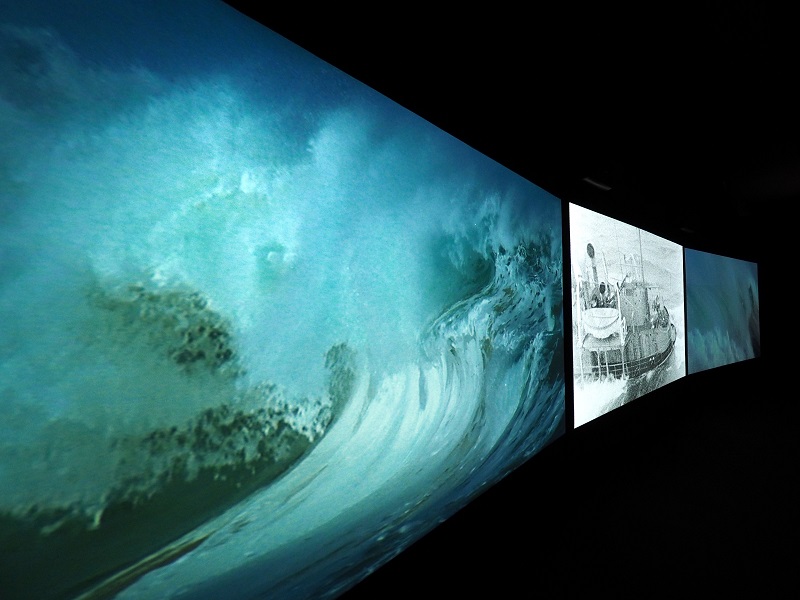

In a darkened first-floor space, Akomfrah re-conjures that awe through an elegantly choreographed 48-minute montage across three screens (pictured right). Each one shows an evolving film collage combining archive and audio material, specially shot footage, old photographs and literary quotations.

In a darkened first-floor space, Akomfrah re-conjures that awe through an elegantly choreographed 48-minute montage across three screens (pictured right). Each one shows an evolving film collage combining archive and audio material, specially shot footage, old photographs and literary quotations.

Taken alone these sights and sounds are striking, but what intrigues Akomfrah is the collective emotive force they can have when they “talk” to each other. At one moment, a gigantic tail fin sonorously slaps the ocean surface; next to it a boat crammed too full with people tosses and turns perilously in a turbulent storm, while nearby gentle waves lap onto a sandy shore at dusk. It’s magnificent, beautiful and unsettling, all at the same time. As the mosaic of films evolve, the clashes and contrasts continue, and with them conflicting sensations and emotions. It’s a mesmerising way to evoke a place that can simultaneously fill us with wonder and fear.

There’s plenty of staggering natural beauty on display above and below the waves from film shot on the Isle of Skye, the Faroe Islands and north of Norway, much of it sourced from the BBC Natural History Unit in nearby Bristol. It’s about as audio-visual an experience as you can get, but on a purely aesthetic level it might remind anybody who’s been there of another immersive visual experience inspired by nature – Monet’s Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. There, too, optical visual effects in multiple tableaux become ever more evocative because they’re displayed together. Yet even that master Impressionist would surely have been envious of how film can capture the fracturing of sunlight as it breaks through a cloud of flying seabirds.

Monet intended his Orangerie as an idyllic refuge from the horrors of World War One. In contrast, Akomfrah forces us to directly engage with the darkest aspects of our interaction with the sea, and their terrible consequences. Some of the most affecting imagery relates to the whaling industry. Majestic shots of whales diving freely in the deep blue jar sharply when shown alongside black-and-white archive of harpoons being readied, or a great, lifeless carcass being eviscerated (pictured above left).

Monet intended his Orangerie as an idyllic refuge from the horrors of World War One. In contrast, Akomfrah forces us to directly engage with the darkest aspects of our interaction with the sea, and their terrible consequences. Some of the most affecting imagery relates to the whaling industry. Majestic shots of whales diving freely in the deep blue jar sharply when shown alongside black-and-white archive of harpoons being readied, or a great, lifeless carcass being eviscerated (pictured above left).

The film opens with footage connected to the story of Vietnamese migrants who attempted to flee persecution after the end of the Vietnam War by packing into tiny boats, hoping to reach Hong Kong. Thousands drowned, and the echo with the current exodus of refugees from Syria is unmistakable.

Using mixed archival material from the past to raise awareness of current political crises is something John Akomfrah has done since he started making films in the Eighties. Yet there’s never a sense that we’re being given a one-track didactic manifesto. He is inviting us to reflect on the present without prescribing a solution for the future. Perhaps that’s why in recent work he has favoured the gallery over the cinema. Some of the most thought-provoking sequences are specially shot, showing figures in costumes from different time periods looking out to sea (pictured below right). They could be waiting for what’s next or reflecting on what has already happened. Either way, a feeling of ambiguity remains.

There’s a similarly open-ended approach to representing the past in the second film on show, Tropikos. This time it’s all on a single screen and specially filmed. It’s billed as an experimental period drama, set during the mid-16th century at the time of the early British expeditions to West Africa. Once again there’s local resonance: part of it was filmed in the Tamar Valley where ships would have sailed from Plymouth, tasked with bringing back riches from Africa. This was only the start and before too long, slaves were the priority cargo.

There’s a similarly open-ended approach to representing the past in the second film on show, Tropikos. This time it’s all on a single screen and specially filmed. It’s billed as an experimental period drama, set during the mid-16th century at the time of the early British expeditions to West Africa. Once again there’s local resonance: part of it was filmed in the Tamar Valley where ships would have sailed from Plymouth, tasked with bringing back riches from Africa. This was only the start and before too long, slaves were the priority cargo.

We’re presented with a series of imagined interactions between the Africans and the British as they encounter each other for the first time. The sense is of new relationships and hierarchies being negotiated and defined. In one sequence, an African man carrying tropical fruit and veg is framed amongst the produce like part of a carefully composed still-life painting so that he looks as much a commodity as the goods he’s transporting. Despite its historical setting, in this film too a connection with the present always remains. In one of the final scenes an African man dressed in period costume wanders down to the water’s edge, gazing towards the horizon at what look like modern-day warships.

In both films it feels like we’re being called to engage more closely with the state we’re in now by looking at events from our past, and their lack of linear narrative or single conclusion doesn’t reduce their power. There’s no stronger way to get people to act than by showing what we stand to lose if we don’t.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment