Standing inside the Gemeentemuseum’s life-size reconstruction of Mondrian’s Paris studio, the painter’s reputation as an austere recluse seems well-deserved. Returning from Holland to France after the First World War, he lived and worked in what seem like impossibly cramped conditions, a narrow and unforgiving-looking bed the only comfort in a room dedicated to the rigorously geometric compositions for which he had become famous. Walls, furniture and even books were painted white, with selected features like the stove and an ashtray left black, and squares of primary colour pinned here and there in experimental arrangements. The room is quite simply a living painting.

If the studio indicates a special sort of monomania, this exhibition, the largest and most comprehensive Mondrian retrospective ever staged, claims to move away from the image of cold obsessive. In fact, the museum’s director and co-curator of The Discovery of Mondrian Benno Tempel explains that the Paris studio was a place where, somewhat improbably, Mondrian “invited guests, transacted business and practised the steps of trendy dances like the Foxtrot, the Charleston and the Shimmy.”

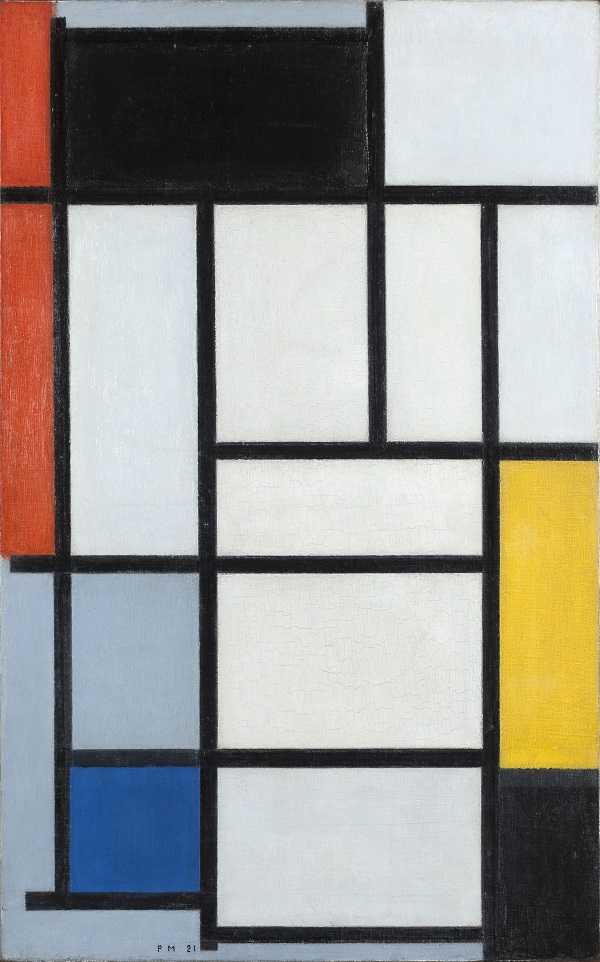

There’s no doubt that our perception of Mondrian the man is informed by the startling frigidity of geometric abstraction which, particularly when viewed in reproduction, can appear calculated and industrial, with little sense of the artist’s hand. When in 2009, the museum began a major conservation campaign, it afforded a reassessment of Mondrian’s practice, close examination of the 300 or so works in its collection revealing the extent to which he experimented and changed compositions in a manner suggestive of an intuitive and painterly painter (pictured right: Composition with red, black, yellow, blue and gray, 1921).

There’s no doubt that our perception of Mondrian the man is informed by the startling frigidity of geometric abstraction which, particularly when viewed in reproduction, can appear calculated and industrial, with little sense of the artist’s hand. When in 2009, the museum began a major conservation campaign, it afforded a reassessment of Mondrian’s practice, close examination of the 300 or so works in its collection revealing the extent to which he experimented and changed compositions in a manner suggestive of an intuitive and painterly painter (pictured right: Composition with red, black, yellow, blue and gray, 1921).

Sociable and enquiring, curious about everything modern from moving pictures to jazz, Mondrian was consistently interested in the work of other artists, and after an academic training and early adoption of the realism of the Hague School, he embraced symbolism, impressionism and pointillism. This was not slavish imitation, however, and from the start his experiments were concerned with finding an idiom with which to achieve his own already well-formed aims.

Even so, it is hard not to feel at least momentarily disappointed by his decision in 1911 to drop everything to move to Paris, having realised that his attempts at cubism, based on newspaper reports and Amsterdam gossip, were some way removed from the experiments of Picasso and Braque. Having arrived in Paris his style changed dramatically, his palette becoming muted in accordance with analytical cubism, a seemingly regressive step after his revelatory introduction of dazzling colour in 1907.

![Piet Mondrian [1872-1944] Oostzijdse Mill in the Evening, c. 1907-1908, Oil on canvas, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag Piet Mondrian [1872-1944] Oostzijdse Mill in the Evening, c. 1907-1908, Oil on canvas, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag](/sites/default/files/images/stories/ART/Florence_Hallett/Mondrian/PM_Oostzijdse%20Molen%20bij%20avond_%201907-1908small.jpg) Hyperbolic as it might sound to talk about Mondrian’s “moment of transformation”, the scope of this vast survey seems to permit just such a description, the best room of the show an apparently step-by-step guide to the artist’s conversion to colour. From the muddy browns and greens of his early landscapes (pictured above: Oostzijdse Mill in the Evening, c.1907-1908), vibrant contrasts of complementary colours make a sudden appearance in The Red Cloud, c.1907, allowing a heightened sense of an experience felt, and the revelation of apparently innate patterns and rhythms in keeping with Mondrian’s growing interest in Theosophy, a popular religious philosophy that claimed an underlying and essential order to the cosmos.

Hyperbolic as it might sound to talk about Mondrian’s “moment of transformation”, the scope of this vast survey seems to permit just such a description, the best room of the show an apparently step-by-step guide to the artist’s conversion to colour. From the muddy browns and greens of his early landscapes (pictured above: Oostzijdse Mill in the Evening, c.1907-1908), vibrant contrasts of complementary colours make a sudden appearance in The Red Cloud, c.1907, allowing a heightened sense of an experience felt, and the revelation of apparently innate patterns and rhythms in keeping with Mondrian’s growing interest in Theosophy, a popular religious philosophy that claimed an underlying and essential order to the cosmos.

Though sudden, the introduction of colour is part of a clear and logical trajectory, marking a new phase as Mondrian progressively clarifies underlying form. Where previously the muddy colours inherited from the Hague School achieved pictorial unity through a limited palette, dazzling complementary colours allowed the further intensification of form and pattern that was a consistent theme throughout his career.

But while he conveys in paintings like Evening; The Red Tree, 1908-10 (main picture), and Mill in Sunlight, 1908, an almost hallucinatory, spiritual experience, in others, like Trees by the Gein with Moonrise, 1907, the potency of a particular motif is self-defeating, straying inexorably towards decoration. Here, and in the total abstraction of the 1920s there is the nagging sense of something lost, and in banishing the intensity of experience that characterises his work up until around 1914, perhaps he simply went too far, falling prey to what Kandinsky described as “mere geometric decoration, something like a necktie or a carpet”. One only has to note the Mondrian themed ties worn by staff at the Gemeentemuseum, to recognise that indeed, geometric abstraction presents as many problems as it solves.

But while he conveys in paintings like Evening; The Red Tree, 1908-10 (main picture), and Mill in Sunlight, 1908, an almost hallucinatory, spiritual experience, in others, like Trees by the Gein with Moonrise, 1907, the potency of a particular motif is self-defeating, straying inexorably towards decoration. Here, and in the total abstraction of the 1920s there is the nagging sense of something lost, and in banishing the intensity of experience that characterises his work up until around 1914, perhaps he simply went too far, falling prey to what Kandinsky described as “mere geometric decoration, something like a necktie or a carpet”. One only has to note the Mondrian themed ties worn by staff at the Gemeentemuseum, to recognise that indeed, geometric abstraction presents as many problems as it solves.

Marking 100 years of De Stijl, the show barely mentions the magazine and artistic movement co-founded by Mondrian with Theo van Doesburg in 1917. The inclusion of some De Stijl chairs is presumably meant to suggest the co-operation fostered between architecture, art and design but only emphasises the sense that in his move to total abstraction, Mondrian emptied his painting of the expressive capacity that would differentiate it from mere design.

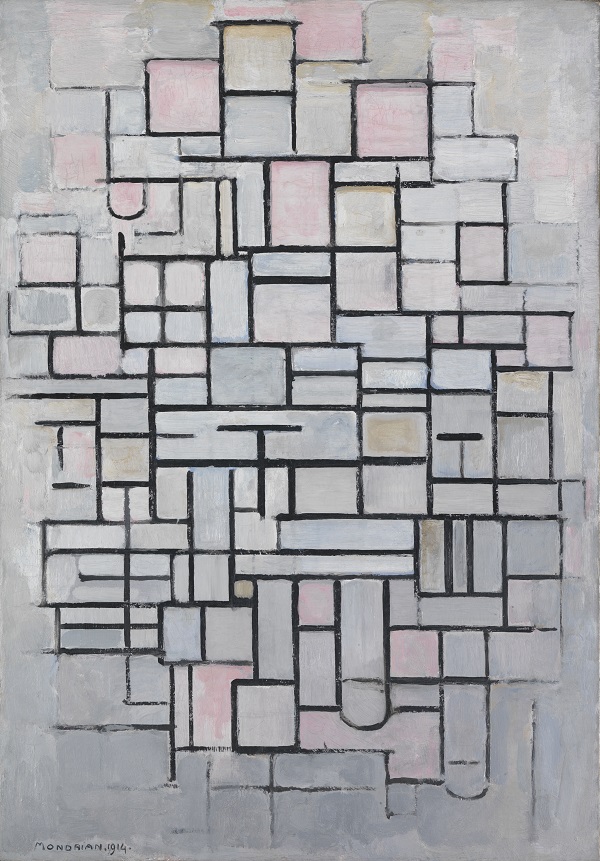

Part of the trouble is that having so clearly shown earlier phases of Mondrian’s development, the crucial transition from his post-cubist experiments to the total abstraction that followed is insufficiently explored (Pictured above left: Composition No.IV, 1914). Discarding all references to observed reality, Mondrian sought to elucidate the fundamental, universal laws of existence, and yet in so doing he loses all sense of subjective experience, arriving at an art that in its reduction to colour line and plane becomes about painting itself.

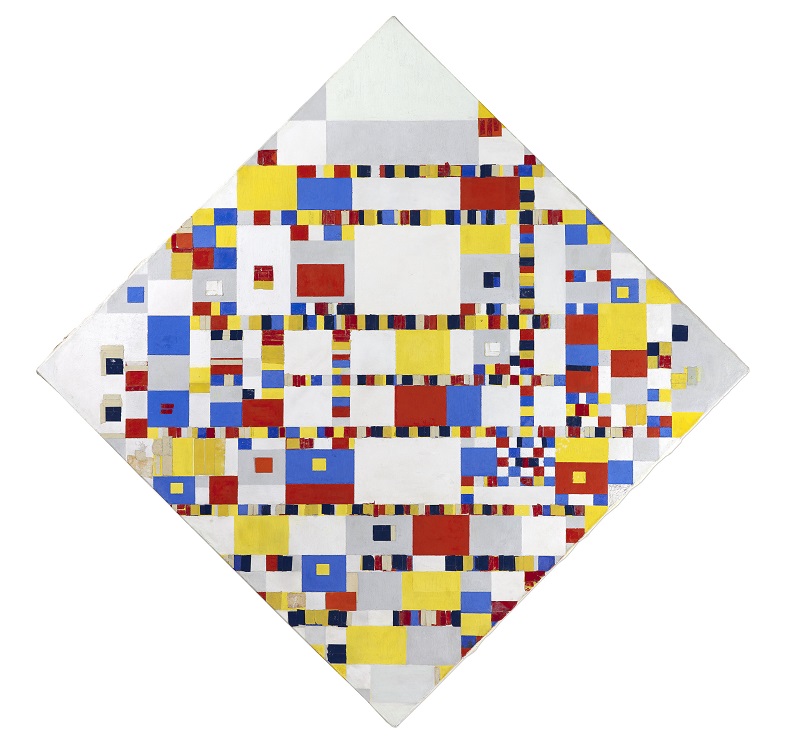

The climax of the show is ostensibly Victory Boogie-Woogie, 1942-44 (pictured right), Mondrian’s unfinished masterpiece that the Gemeentemuseum is rightfully proud of, cementing the museum’s status as the world's foremost Mondrian collection. But hung on its own, it loses any sense of its real significance; in its dynamism, inspired by the syncopated rhythms of jazz, it not only builds on the sense of movement that had been developing in his work during the 1930s, but returns, in a sense, to the previously abandoned realms of representation.

The climax of the show is ostensibly Victory Boogie-Woogie, 1942-44 (pictured right), Mondrian’s unfinished masterpiece that the Gemeentemuseum is rightfully proud of, cementing the museum’s status as the world's foremost Mondrian collection. But hung on its own, it loses any sense of its real significance; in its dynamism, inspired by the syncopated rhythms of jazz, it not only builds on the sense of movement that had been developing in his work during the 1930s, but returns, in a sense, to the previously abandoned realms of representation.

If the presentation of Victory Boogie Woogie is symptomatic of the hagiographical nature of this show, fascinating asides in the form of letters and photographs, as well as a selection of commissions go some way to offsetting this. A selection of Mondrian’s commissions are a reminder of the drudgery of the artistic life, a selection of boring portraits and copies paying the bills as he pursued his revolutionary, but not always financially rewarding vision of a new art for a world transformed.

- The Discovery of Mondrian at the Gemeentemuseum Den Hague, The Hague until 24 September 2017

- The reconstruction of Mondrian's Paris studio opens on 10 June 2017

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment