The title of Joy Gregory’s Whitechapel exhibition is inspired by a proverb her mother used to quote – “you catch more flies with honey than vinegar” – and her aim is to seduce rather than harangue the viewer.

It’s a good stratagem, especially if you are pointing to things your audience may prefer not to consider. And Gregory’s images can be beautiful (the seduction); but in order to avoid a diatribe, she often approaches her subject obliquely and quietens her voice to a whisper, requiring the viewer to pay close attention and hone in on the message.

If most photographers use the camera to look outwards and record what they see, Gregory employs the medium more as form of self-exploration and enquiry. And the question that seems to haunt her and to underpin much of the work is “Where do I belong?”

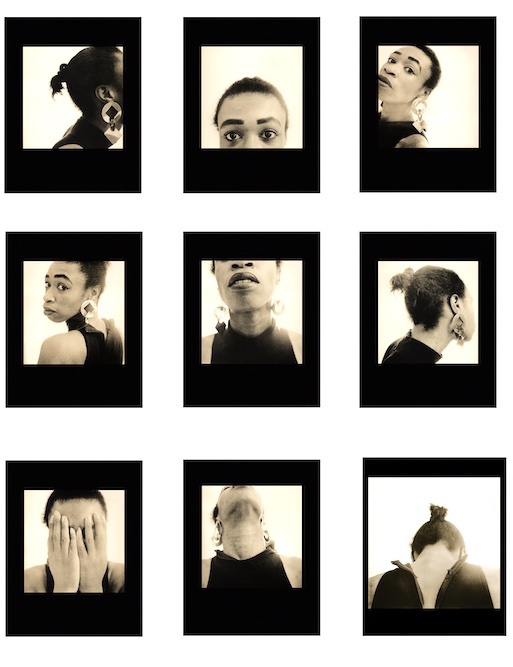

In a series of early self-portraits (pictured above), she offers glimpses of her head and shoulders. It’s feels as if she is passing through rather than occupying the frame and questioning whether, as a black woman, she has the right to take the space. And in the series Women and Space (1987-1999), she positions herself awkwardly in domestic interiors as if feeling uncomfortable or unwelcome there too.

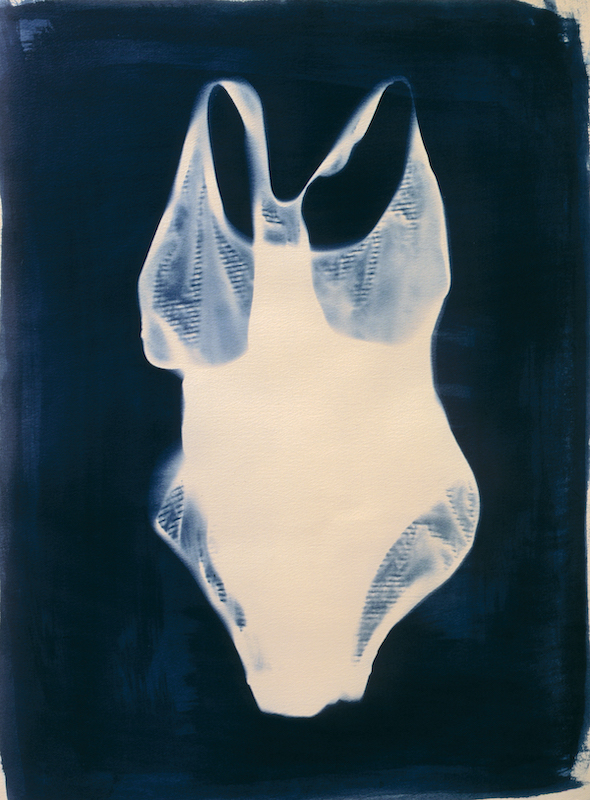

In several series that explore the construction of the female identity, Gregory uses Victorian techniques – such as cyanotypes (blue prints) and kallitypes that have a ghostly, archival quality – as though to remind us that the struggle to conform to expectations goes back a long way. Objects of Beauty (1992-5) records some of the tools used to construct the desired appearance as dictated by the fashion and beauty industries, while Girl Thing (2002-4) records items like a corset, bras, swimsuit (pictured below), bikini and string of pearls traditionally associated with notions of “femininity”.

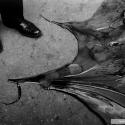

In other series she addresses the gulf between rich and poor. For The Handbag Project (1998-) Gregory photographed the designer handbags she found in charity shops in South Africa. Bought by white women whose privilege depended on the low paid work of black staff, some were still in their cellophane wrappings – surplus to requirements. “One imagines Madam's concerns”, she writes, “the weather, the guest list, the lazy and untrustworthy domestic staff, Paris Vogue, the quality of beading on a new evening bag … ” And in Cinderella Tours Europe (1971-2001) (pictured below) she takes a pair of golden high heels to places like Venice and Cadiz that those impoverished women could only dream of visiting.

For me the highlight of the downstairs gallery is a series of transparencies of interiors and still lifes featuring white painted bottles, scissors, dead daffodils and vases of tulips. These Morandi-like compositions have a wonderfully calm serenity, as though they represent a place where, at last, the artists feels at home. But the images are so tiny you could easily miss them altogether.

The Blonde (1997-2010) is an exploration of the equation between fair skin, blonde hair and beauty. Samples of hair and the products used to bleach them appear alongside photographs of white people trying to pass as blondes or black people sending up the desire by sporting hilarious wigs. Fairest is a film in which Gregory asks bottle blondes why they chose to bleach, but their disappointingly obvious replies throw little light on the implicit racism underpinning the myth.

Another preoccupation is the alarming rate at which languages are disappearing. 7,0000 tongues are spoken worldwide, but nearly half are endangered. Every 2 weeks another one dies in a loss that signals the erasure of a whole culture and way of life. In Kalahari (2005-10) Gregory talks to the bushmen of the Kalahari, a marginalised group whose click language has already been lost, while in Gomera (2010) she records El Silbo, a beautiful language of whistles resembling birdsong that has recently been revived.

The issues are important so why does Gregory distract one’s attention by complicating the viewing experience? In Gomera she pulls focus on the whistling man and palm tree behind him so they alternately lose clarity and turns blue skies colourless by filming the coastline through dirty windows. Kalahari, is hard to watch because the image is edged by glimpses of other frames. If it were celluloid you’d think the film was misaligned with the gate, but this is video which suggests the effect is intentional.

The same technique is used in A Little or No Breeze 2021 (main picture). The film forms part of Seeds of Empire, a project inspired by the notes kept by physician and naturalist, Sir Hans Sloane on a trip to Jamaica in 1687 to collect plants and seeds. Sloane’s collection of artefacts was so vast that, when he bequeathed them to the nation, they formed the basis of the British Museum, the British Library and the Natural History Museum – symbols of Empire and Britain’s dominance.

Snippets from his diary recording the weather during his voyage are intercut with images of Rose, a house slave whose severe depression Sloane treated with herbal remedies. Beautifully shot scenes of Rose standing, broom in hand, in a calm interior or sitting slumped on the stairs switch from black and white to colour and from stills to slo-mo video – complications that, along with the odd framing, undermine the poetry of a moving juxtaposition which reminds one of those other, involuntary voyages that brought slaves like Rose to the island.

The sister film Observation Rose consists of stills of the exotic plants that Sloane collected and the botanical gardens built to house them captioned with the notes he kept detailing the remedies he used to treat Rose’s depression. Meanwhile, on the soundtrack, Jamaican immigrants describe the expectations that led them to come to Britain compared with the reality on the ground. The layering makes the film difficult to follow, but this time it works in that it mirrors the exploitative web of connections that, over the centuries, has governed Britain’s relationship to the colonies.

Gregory describes herself as “very shy” and her approach to these important projects often seems so tentative or so oblique that she risks losing her potential audience. While I was at the exhibition, for instance, a group of teenagers arrived; they wandered through the galleries, but the work made so little impression on them that they didn't stop to engage with anything. Sometimes, shouting can be necessary.

Joy Gregory: Catching Flies with Honey is at the Whitechapel Gallery until 1 March 2026

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

- All embedded pictures © Joy Gregory (DACS)

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment