Not the least interesting aspect of Give Us The Money, an examination of the effectiveness of famous pop stars campaigning to end poverty in Africa, was how historical it felt. Homing in specifically on Bob Geldof and Bono, who between then have spent decades hectoring the public, berating politicians and schmoozing billionaires with a view to alleviating the sufferings of millions of starving Africans, it was a glimpse into a lost world of stadium rock, furry non-HD video and political yesterday's men, like Gordon Brown and George W Bush.

The commentary seemed to promise a controversial outcome, hinting that St Bob and St Bono might in the end be shown up as grandstanding fakes whose noisy breast-beating signified nothing other than loads of free publicity for themslves. In the event nobody went that far, though director Bosse Lindquist unearthed a number of commentators prepared to take a less-than-adulatory view of the Live Aid twins. In particular there was Dambisa Moyo, an economist and author of something called Dead Aid.

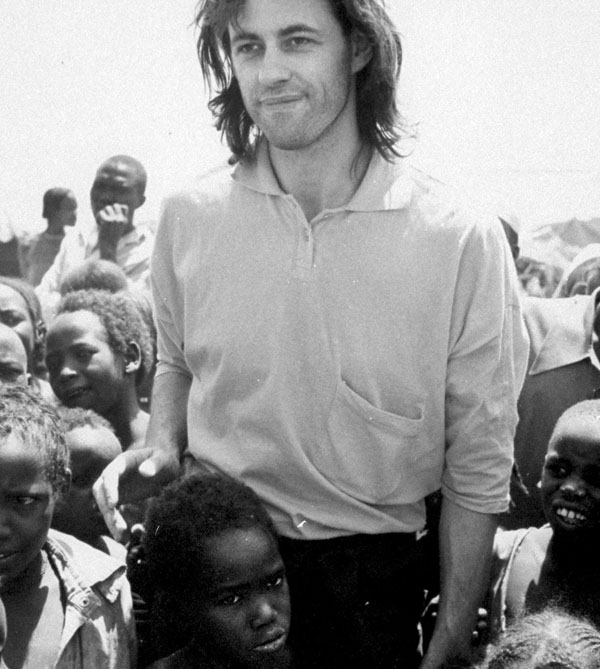

One thing she didn't like was the way ghastly images of starving Ethiopians had come to define the entire playing field of aid and African development. "It is so damaging psychologically to a whole continent, a whole population of people, to portray them in this manner," she postulated. "It is basically laced with pity." (Geldof in Africa, pictured right)

One thing she didn't like was the way ghastly images of starving Ethiopians had come to define the entire playing field of aid and African development. "It is so damaging psychologically to a whole continent, a whole population of people, to portray them in this manner," she postulated. "It is basically laced with pity." (Geldof in Africa, pictured right)

I couldn't see the "pity" point. Nobody wants to be pitied, but if the watching world hadn't felt pity, there may have been no aid to famine victims at all. By even the most sceptical yardstick, famine relief did help to save some of the most desperate victims, even if the Live Aid/Band Aid legacy isn't as grand as has been claimed by the belligerent Geldof.

But, as Moyo added, if "the celebrities" were motivated by promoting economic growth and poverty reduction in sub-Saharan Africa, "they have failed miserably. There's far too much hubris going around... let's have a bit more humility about what we can achieve."

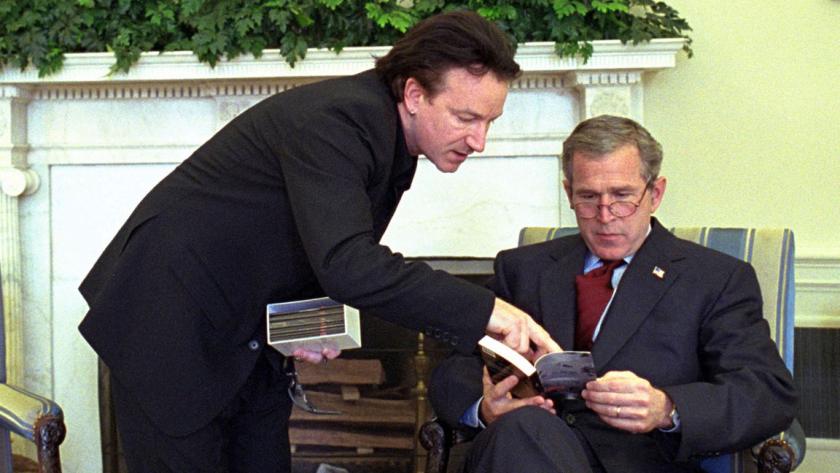

The other side of the coin was the film's extensive account of how Bono, in particular, had launched a sustained charm-and-blarney offensive on such citadels of global power as the G8 and the US government. You had to admire his sense of purpose, not to mention his determination to soak up as much information as he could about how economics and geopolitics work. He was also smart enough to grasp that the aura of being U2's vocalist worked just as well on ageing politicians as it did on 20-something rock fans, and the simple device of inviting veteran ultra-conservative senator Jesse Helms to a U2 show helped to break down the objections of the US Congress to boosting funding to combat Aids in Africa (Bono at Live Aid, Wembley Stadium 1985).

Some sympathetic light was also shed on George W Bush, who is ridiculed as a redneck halfwit in fashionable circles, but who was genuinely horrified by the African Aids crisis and stuck his neck out to guarantee a sizeable American aid package. Then he spoiled it all by going to war in Iraq.

Some sympathetic light was also shed on George W Bush, who is ridiculed as a redneck halfwit in fashionable circles, but who was genuinely horrified by the African Aids crisis and stuck his neck out to guarantee a sizeable American aid package. Then he spoiled it all by going to war in Iraq.

Bono also experienced many bruising reminders of how politics will always be "the art of the possible". Having persuaded Bill Clinton (whom he'd got to know during the peace process in Northern Ireland) to make a speech saying the US would forgive 100 percent of African debt, Bono thought his mission was accomplished. However, he added, "there's this really bizarre moment when you discover the President of the United States is not in charge." Bill could say whatever he liked, but that didn't mean Congress would ratify it. Besides, it became clear that the African debt was so colossal that it could never have been paid off whether the USA waived it or not.

The ending was equivocal. "The specific impact of Geldof's and Bono's campaigning is unknown," said a caption. On the other hand, malaria deaths have been halved, millions of people have received treatment for HIV infection, and deaths from starvation have fallen dramatically. Africa, the message seemed to be, wanted to take the credit for healing itself.

Add comment