Blame the weather: it works every time. In 1858, the long hot summer thwarted the building of an 11-mile glass-covered network of roads and railways that would have linked all existing London stations, crossed the river in three places and, it was believed by its architect Joseph Paxton, relieved the congestion that was making crossing the capital an anxious business.

His track record was proven, and spectacular, as discovered in Dreaming the Impossible: Unbuilt Britain, the first of three programmes visiting castles in the air – high-minded, often high-flying, projects that never left the drawing-board. Indeed, as architect Norman Foster points out, the foundations are only ever laid on one in 10 architectural designs. But, despite the success of his spectacular glass houses at Chatsworth, Paxton was overtaken in his scheme for London by the Great Stink, the overpowering stench that forced all who could to leave the capital, caused by millions of gallons of warm effluent. Joseph Bazalgette’s sewerage scheme was considered more urgent than a giant overground glass tube, and Paxton’s Great Victorian Way (main image) was never realised.

Architectural investigator Olivia Horsfall Turner (pictured right), in a completely engaging and fact-packed programme with minimal fuss, visited Chatsworth, where Paxton developed his wood-and-glass constructions; Kew Gardens where the race to bring to bloom the Amazonian water lily was won by glass technology; and Pilkington glass in St Helens, Lancashire, where an old hand called the float glass the most significant invention of the 20th century. By pouring molten glass on to molten tin, it forms a skin only 6.4mm thick, the perfect window glass, and at a limitless size. Some bright spark dubbed this the Glass Age, and British townscapes were transformed.

Architectural investigator Olivia Horsfall Turner (pictured right), in a completely engaging and fact-packed programme with minimal fuss, visited Chatsworth, where Paxton developed his wood-and-glass constructions; Kew Gardens where the race to bring to bloom the Amazonian water lily was won by glass technology; and Pilkington glass in St Helens, Lancashire, where an old hand called the float glass the most significant invention of the 20th century. By pouring molten glass on to molten tin, it forms a skin only 6.4mm thick, the perfect window glass, and at a limitless size. Some bright spark dubbed this the Glass Age, and British townscapes were transformed.

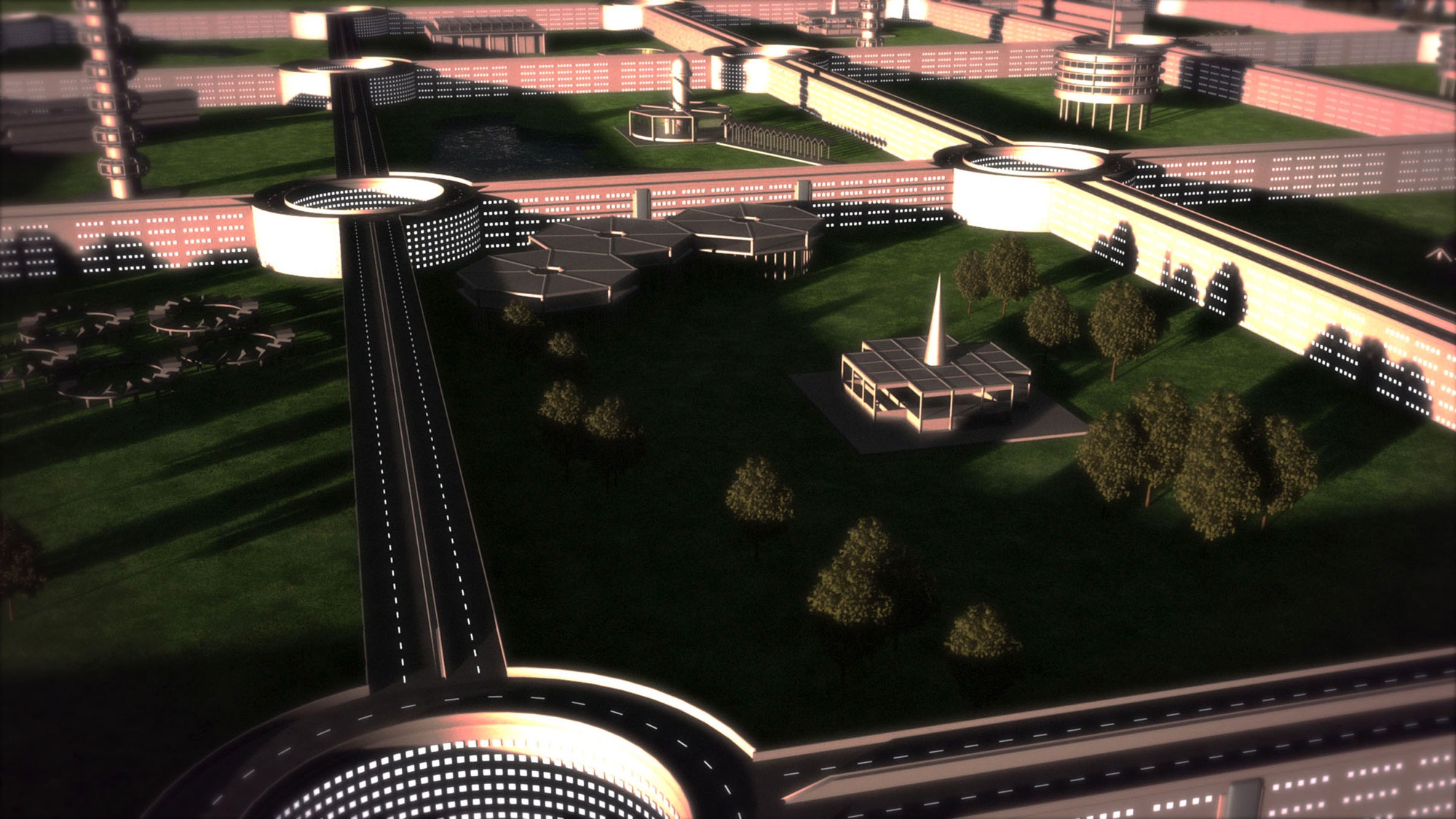

Foster says sheet glass released us from the cave. Not all architects had the same ideal. Another failed scheme would have created a two-tier society: the working class would have traversed the city on underground roads, and only the wealthy would have seen the light. A railway down the middle of the Thames was never going to fly. King’s Cross today conspicuously lacks the once-mooted airport with radial runways. And what sounds like a satirical swipe at the combustion engine, Motopia (below left), probably failed because, despite its intentions of reserving ground level for people and raising cars on a grid of aerial highways – glass-borne, of course – the rigid rules for living by architect Joseph Jellicoe must have seemed offputting. Most people, after all, do not necessarily want to shut their windows just because they have the radio on.

If it was sewerage that topped the to-do list in the 19th century, it is clearly living with (or without) the car that dictates 21st century town planning. The solution may not be the doomed 1930s Regent Street motorway, or the multi-storey car park on Trafalgar Square or the superhighway looming over Tower Bridge. But, said Foster, it is the public spaces and not the individual buildings that determine the quality of city life. His heart is set on connecting the North with mainland Europe via improved rail, and a new airport on his Thames Hub. And that, of course, is causing a great stink of a different sort.

If it was sewerage that topped the to-do list in the 19th century, it is clearly living with (or without) the car that dictates 21st century town planning. The solution may not be the doomed 1930s Regent Street motorway, or the multi-storey car park on Trafalgar Square or the superhighway looming over Tower Bridge. But, said Foster, it is the public spaces and not the individual buildings that determine the quality of city life. His heart is set on connecting the North with mainland Europe via improved rail, and a new airport on his Thames Hub. And that, of course, is causing a great stink of a different sort.

Add comment